Bike Tests: Design Specifics vs. Intended Use

There are two common yet different approaches to testing products:

- You can compare design specifics. For example, you test hybrid bikes with disc brakes. Or in the car world, mid-size SUVs. You figure out which company makes the best one in that category.

- You can look at the intended use and figure out which design will work best. For example, you try to find the best bike for carrying its rider and briefcase in urban traffic, year-round. Or the best car to haul a family of four, a baby jogger and a dog.

With Approach 1., part of the test results is a foregone conclusion: The best hybrid bike with disc brakes will be, well, a hybrid with disc brakes. In the SUV test, you do not ask whether an SUV is a good solution to carrying a family of four, a baby jogger and a dog. These underlying assumptions are not examined. The test is “thinking inside the box.”

With Approach 2., the test result is much less predictable: Even the best SUV may be less than ideal. Something entirely different may be best for the purpose; it may even be something that does not exist yet. The reviewers are “thinking outside the box.”

The industry likes Approach 1. This gives them a clear target: “Design an SUV that beats the Ford Explorer.” Or: “Come up with a derailleur that shifts as well as Shimano Dura-Ace.”

For testers, this is easy as well. You compare a handful of products and declare a winner. There is no need to think about the “what ifs” that require additional research, thought and imagination.

For consumers, Approach 1 is less satisfactory, because it does not examine whether the underlying assumptions are valid. The best solution to the “4 people, baby jogger, dog” transportation problem may be a station wagon, a mini-minivan or something else that did not enter the discussion. For carrying a cyclist and their briefcase, a hybrid may not be ideal, and a better choice may be an urban bike with integrated fenders and lights. The briefcase might be best carried on a front rack (with suitable geometry) that allows riders to start from a light without wobbling.

Of course, Approach 2 also can be unsatisfactory. If a reader really likes the image or looks of an SUV, they might not want to read that they really should buy a different car. “Just tell me which of the five SUVs on my list is best, and leave me alone,” that reader may think. Worse, the “ideal” product may not even be easily available.

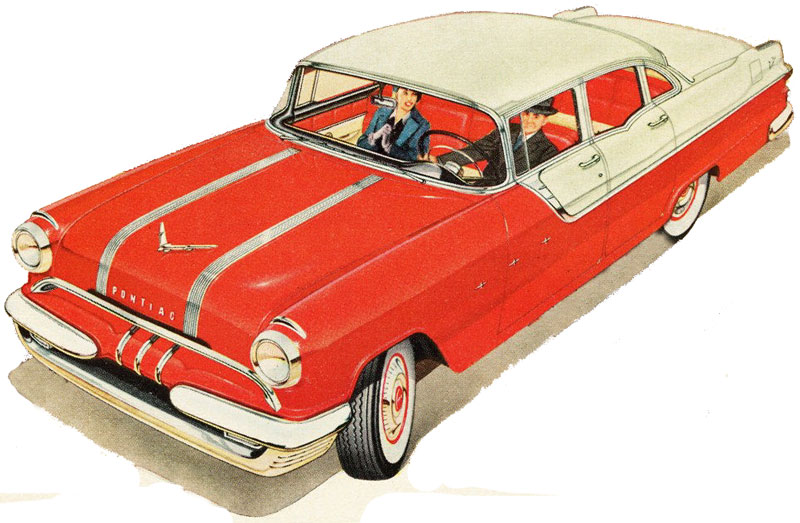

If you were car-shopping in the U.S. in 1955, you probably were thinking which tailfin shape you liked better and whether to pay a little extra for the new 427 cubic inch V8. Then you picked up Road & Track and read that unibody construction was better than Detroit’s separate chassis, and had you considered the new Alfa Romeo (below) with its efficient 1.3 litre engine and excellent handling?

Of course, that Alfa was not easily available, and getting it serviced by people who had never seen such a car was difficult at best. So there were real practical reasons to buy the tailfinned behemoth instead. Even so, Road & Track helped push American makers toward building better cars by showing what was possible, rather than what was easily available.

At Bicycle Quarterly, we try to combine both approaches. On the one hand, we consider what riders can buy today, but on the other hand, we often suggest improvements to the products we test.

Today, cyclists have more choices outside the “standard” categories than just a few years ago. I don’t think the mainstream magazines with their “Best Road Bike for under $2000” approach caused the industry to broaden their scope. Instead, many people outside the industry pushed for these designs, and small makers introduced them. Finally, the bigger manufacturers are beginning to copy them, to the benefit of every cyclist.