Myths Debunked: Wide Tires DON’T Need Wide Rims

Our series of ‘Myths in Cycling’ continues with a look at rim width. You often hear that wider tires should run on wider rims. Intuitively, that seems to make sense – match the wider tire to a wider rim. You also hear that wider rims make the tire handle more predictably.

The idea is this: A wider rim makes a tire more U-shaped (left), rather than O-shaped (right) on a narrower rim. The sidewalls are more vertical, so they can better support the weight of the rider. This is said to make the tire flex less, so it corners more predictably.

When we first started experimenting with wider tires more than a decade ago, I was concerned: There weren’t any really wide rims available back then. I mentioned this to framebuilder Peter Weigle (above, in the center). His response surprised me: “I don’t think rim width matters. We used to race mountain bikes on narrow Mavic road racing rims. I actually preferred how the bike handled with the narrow rims.” This came from the guy who won the cyclocross national championships on a mountain bike!

When I thought about what Peter said, I realized that it made sense. The extreme case of an O-shaped tire is a tubular: It’s perfectly round, and it touches the rim only at its bottom. If vertical tire sidewalls were essential for good handling, tubulars would have fallen out of favor long ago.

Tubulars remain popular in pro racing because they corner very well. Given the choice for mountain stages, many pros in the Tour de France (above) ride on tubular tires. Tubulars absorb shocks better, which means they stick to the road better and have more traction. That they are O-shaped is a feature, not a drawback.

What is going on here? With supple tires, the sidewalls are so stiff that they hold up the weight of bike and rider. You can see that when you deflate the tire: The bike sinks down until the rim touches the ground. When you ride on supple tires, it’s the air that supports your weight.

And so rim width doesn’t really matter. On my Firefly (above), I run 54 mm-wide Rene Herse Rat Trap Pass tires on 20 mm-wide (internal) rims without any problems. And the Firefly corners better than most racing bikes, because it has so much more rubber on the road. Like the pros on their tubulars, I never notice any squirm caused by the O-shaped tires.

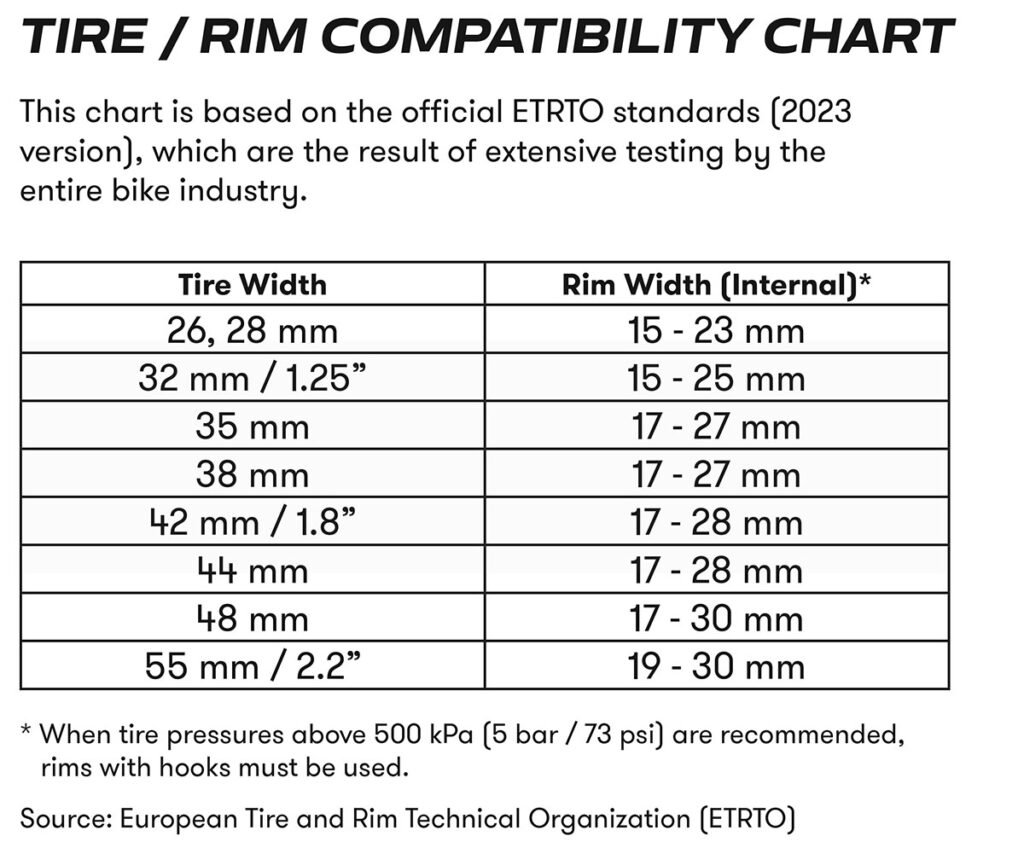

When you look at the ETRTO chart for tire and rim compatibility, you can see that my Firefly’s 54 mm tires on 20 mm rims are no problem. I could even go as low as 19 mm.

The chart shows that the real concern is at the opposite end of the spectrum: If the rim is too wide, tire pressure no longer pushes the bead strongly against the rim sidewall. This can cause the tire to blow off the rim, especially if you run the tire tubeless. (A tube reinforces the rim/tire joint and adds an extra margin of safety.)

What if you run stiffer tires? Would you want to match tire and rim widths to take advantage of the sidewall stiffness? I’m not sure. When I was at Paul Camp a few years ago, I got to ride a wonderful Steve Rex monstercross bike, shod with relatively stiff mountain bike tires (above). When I first rode the bike, the tires felt very harsh. I let out air until the bike began to float over the rough gravel in Paul’s parking lot. I loved riding the Steve Rex, and I pushed it harder and harder.

When we reached some really technical terrain, the front tire’s sidewall collapsed as the tire hit some rocks while the fork was turned. It was very sudden, and more extreme than I had experienced when running supple tires at too-low pressures.

When Paul’s mechanic saw this, he checked my tires and shook his head: “You need to run about 30 psi in those tires!” Now 30 psi (2 bar) is more than I run in my Rat Trap Pass tires on pavement! Perhaps the mechanic was overestimating my weight, or adding a factor of safety, but it appears that when you ride really hard, tires with stiff sidewalls need almost as much air as supple tires.

There’s a reason for that, too. Imagine your bike’s tires as two springs, which work together to support the weight of bike and rider. One spring is the rubber of the tire. The other spring is the air inside the tire. Both springs work together – with a stiff tire, you need less air pressure (and vice versa).

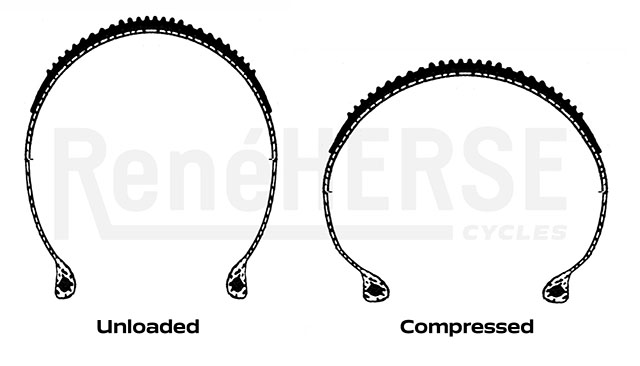

But as I saw at Paul Camp, relying on the tire sidewall for support has a disadvantage: Once the tire starts to compress, it bows outward (right). It goes from U-shaped to O-shaped. The more it bows, the easier it becomes to flex. Once the tire starts to collapse, it becomes less and less stiff, and there is almost no stopping this. This is called a regressive spring rate. It explains why the collapse of the mountain tire on the monstercross bike was so extreme.

A regressive spring rate is a big No-No for suspension design—because of that run-away collapse as you push harder on it. Suspension systems usually use the opposite, a progressive spring rate, so the spring becomes harder the more you compress it.

Using air to support the bike results in slightly progressive spring rate: Pressure goes up slightly as the tire deforms. That’s what you want—a spring that gets slightly harder (and not softer) when you compress it.

This suggests that even stiff tires may work better on relatively narrow rims: The O-shaped tire will be easier to flex and thus more comfortable. Without the tire ‘standing’ on its sidewall, you’ll have to run a little higher tire pressure, but then you don’t have to worry about the tire collapsing.

In other words, with vertical sidewalls you have a relatively stiff tire at first, but when it hits a bump, it becomes less and less stiff, until it suddenly collapses. Better to start with the tire being O-shaped, so it’s always able to flex a bit more. When Peter Weigle mentioned that he preferred the ride of wide mountain bike tires on narrow rims, I believe that’s what he was talking about.

With a supple tire, it’s mostly air holding up the bike. The spring rate is slightly progressive, and you can run a lower total spring rate – less stiffness of tire and air combined. That means you get a tire that absorbs shocks better and is more comfortable. And because the supple casing absorbs less energy as it flexes, it’s faster, too.

What this means in the real world:

- Rim width doesn’t matter for supple high-performance tires. You can run our widest Rene Herse tires on relatively narrow rims – or on wide rims. There will be no discernible difference in how the tires feel and corner.

- Don’t use a rim that is too wide for your tires. Refer to the ETRTO chart (above) for guidance.

- Using the tire sidewalls to hold up the rider results in a regressive spring rate. If you hit a bump that’s big enough to flex your tire, the tire can collapse suddenly.

Aerodynamics

There is one other reason to prefer wide rims and a ‘U-shaped’ tire: With aero wheels, this improves the airflow at the tire-rim interface. An O-shaped tire looks like a pear, not like a teardrop. That’s not aero… With narrow tires, you can get an almost perfect aerodynamic shape with a deep-dish rim if the outside of the rim is just a little wider than your tire. With wide all-road and gravel tires, the optimum shape needed to get smooth airflow requires a super-deep rim that’s not practical for real-world riding. That’s a subject for another post (see below).

Further reading:

- Why supple tires run at higher pressures, yet are more comfortable.

- Other posts of the ‘Myths in Cycling’ series

- Aerodynamics of Gravel Bikes

Note: This post has been updated with the 2023 ETRTO Rim/Tire Compatibility Chart.

P.S.: There is one additional consideration—if you run cantilever brakes, your rims need to be wide enough that the brake pads don’t hit the tire when the brake opens and the pads swing out- and upward.