Nivex or eTap?

We’re offering the 80th Anniversary Rene Herse bikes with a choice of two drivetrains: either SRAM eTap or a Nivex rear and Rene Herse front derailleur. It’s a choice between best electronic or the best manual shifting. Both the current Nivex and modern electronic drivetrains stand at the pinnacle of a long line of development.

Modern electronic shifting offers positive, fast and reliable shifts. It’s solved most of the problems that could occur with cable-operated brifters. The computer automatically trims front derailleur, so you don’t get the annoying chain rub that was inevitable in some gears with mechanical systems that didn’t allow trimming the front derailleur at all. Electronic shifters also are more durable – on the mechanical brifters, the edges could wear off the small cams and ratchets if the rider shifted quickly and released the lever before the gears had engaged. With the electronic systems, each shift is the same, and each is perfect. The light action of the paddles is much more pleasant than the mechanical systems that could fatigue your hands during long rides. (Lael Wilcox once lost a fingernail during the TransAm just from having to push so much on the shift lever.)

SRAM’s eTap has the additional plus that it’s wireless, which helps when disassembling the bike, Rinko-style. The small down side of all electronic systems is the need to charge the batteries once a month or so. And the looks of the bulky mechanisms take a little getting used to, especially when juxtaposed with the slender Rene Herse cranks.

Most production front derailleurs have another issue: They are designed for 53-tooth (or even larger) chainrings. That necessitates a large radius of the cage, and when you run smaller chainrings, they no longer follow the contour of the rings. You can see that in the photo above with a 50-tooth big ring, and it becomes much more pronounced if you run a 46- or even 42-tooth big ring. In practice, the derailleurs usually shift fine, but a smaller chain gap would be better, especially for downshifts to the small ring.

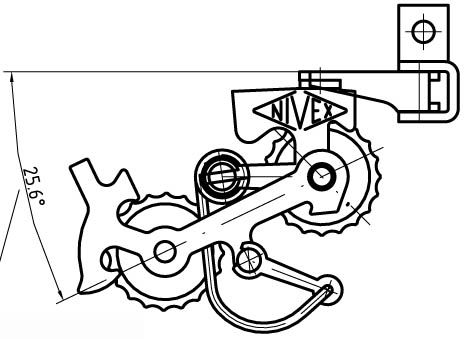

The Nivex may seem like an anachronism, but it was designed by people who understood more about shifting than almost anybody else for the next few decades. The parallelogram is oriented to keep the chain gap constant over a wide gear range – something that few other derailleurs did until SunTour introduced the slant parallelogram in 1964.

The chain tensioning spring acts on a compensating lever, so the chain tension is the same in all gears. There is none of the chain slap that you used to get when riding in the small chainring and on small rear cogs. Modern gravel and mountain bike derailleurs use clutches to achieve the same result, but that comes at the expense of weight and complication. The desmodromic operation of the Nivex is another plus – not just because it offers faster and more precise shifts, but also because you’ll never have to worry about a ‘ghost shift’ when your frame flexes. Of course, modern electronic derailleurs also work with a push-pull mechanism and (finally) got rid of the return spring.

So in effect, the Nivex presaged all the features that make modern derailleurs great, but it combines these features in a lighter and more elegant package. And since it mounts under the chainstay, it’s tucked away rather than sticking out like dropout-mounted rear derailleurs. That means the Nivex is protected if the bike falls over, since the derailleur doesn’t hit the ground at all. (No more bent or broken hangers!) It’s also less likely to hit rocks or sticks when riding across rough terrain. It really makes you wonder why all current derailleurs still mount to the dropout. That made sense in the 1940s, when derailleur makers needed an easy way to retrofit racing bikes with no provision for derailleurs. You’d think that in the intervening 80 years, somebody would have come up with a better solution that doesn’t require carrying spare derailleur mounts!

Starting with this brilliant design, we’ve moved the Nivex into the 21st century. We slanted the parallelogram and updated the geometry for even better shifting, especially with the wider range of modern cassettes. Superlight construction drops the weight to 178 g – lighter than most modern racing derailleurs and much lighter than gravel derailleurs with a clutch to prevent chain slap. Sealed-bearing pulleys roll smoothly and silently, and the entire derailleur is rebuildable, should the need arise. The shift lever can be set up for indexing with up to 11 cogs, or in a pure friction mode. We’re also making special dropouts that open slightly to the rear, to facilitate removing the wheel despite the fenders.

Another big plus for me is the reliability and longevity of the Nivex: The (used) derailleur on my first Rene Herse is still going strong after 10 years and more than 40,000 km (25,000 miles).

Drawbacks? Setting up a desmodromic derailleur is a little finicky, because you need to get the cable tension just right. The Rene Herse Nivex will come with in-line cable tensioners that you can use to make things easier. And since there’s no upper pivot, the maximum cog is limited to 30 teeth for optimum performance – not a really big deal if you combine it with a sub-compact double. With 42×26 chainrings, you still get a gear that’s smaller than 1:1. There’s one more thing: Since the chain wraps around the rear cogs on three sides, the rear wheel can’t just drop downward – you have to move the chain off the cog by hand and tilt the wheel to remove it. The original Nivex came with a chainrest that allowed shifting the chain onto the frame, and removing the wheel without touching the chain at all. My first Rene Herse has that feature. It’s a neat party trick, but I have so few flats these days that I prefer to have an extra cog on the back.

What about the lever-operated Rene Herse front derailleur? It’s a very simple system with a very direct action. It’s not difficult to use – the lever is right next to your water bottle, so if you can retrieve a waterbottle, you can shift this derailleur. I’d say the main advantage is ultralight weight – not only is the derailleur superlight, but it also does away with shifter cable, housing and shift lever. Another plus is that, since it’s hand-made, the cage matches the curvature of the sub-compact chainrings most of us run these days. Drawbacks? Well, you can’t really pedal at a high cadence while you shift, so if you shift on the front a lot, this derailleur isn’t ideal. If you use your compact double mostly as a One-By-plus-Granny, then it works great. And since the sliding tubes have some play – otherwise, they’d jam if dirt gets inside – they can rattle a bit on rough roads. The solution is simple: Put a little beeswax on the inner part, and it’s quiet.

In the end, the two systems – the electronic eTap and the Nivex – are really quite similar. Both are desmodromic: They push and pull the chain in both directions, which makes for consistent and fast shifts. They also share a light touch that matches the control weights of steering and brakes on these bikes.

Which would I pick? It really depends on the ride. If a ride forces me to be always at my limit, then I can’t plan my shifts, and I’d prefer electronic shifting. For example, if the road is rough and steep, and my tires aren’t quite wide enough, I’ll find myself suddenly bogging down and needing a shift just as I rise out of the saddle. With eTap, I can stand on the pedals, push the lever and only lightly let up in my pedaling as the new gear engages. However, on longer rides like Paris-Brest-Paris (above) or the Oregon Outback, where I’m riding within my comfort zone, I prefer the involvement of the manual drivetrain.

When BQ’s second tester Mark told me that he wanted a Rene Herse, I asked him, almost in jest, which shifters he’d want. I know that Mark has no nostalgia for mid-century French bikes. His approach to bikes is very pragmatic – it’s all about the ride for him. For him, the best bike is a bike that disappears when he rides it. I was surprised that he chose the Nivex/Rene Herse derailleurs. Here’s why:

“One of the biggest benefits of riding BQ test bikes is the opportunity to develop a very clear sense of what I like in a bicycle, and one of the things I like most is a sense of simple, refined competence – what I would call elegance. The thing that stood out when I rode Jan’s Rene Herse bike for the first time was its elegance. Before we even finished the test ride I decided I wanted a Rene Herse for myself.

“When Jan asked if I wanted the Nivex rear and Rene Herse front shifters, I said, “Of course!” The shifting was a major part of what I liked about the bike, particularly the Nivex rear derailleur. The unique thing about shifting the Nivex is that – because there is no return spring – the shift lever has a lighter, more precise movement than any other mechanical shifter I’ve used. It made me realize how much force and overshifting has always been a part of shifting other bikes. Shifting the Nivex feels like placing a chess piece. It’s elegant.

“The Rene Herse front derailleur is a simpler mechanism with a simpler job. Pushing the chain back and forth across the chainrings is accomplished with a minimum of moving parts and the drop of a hand to the seat tube. Again, it’s an elegant solution.

“The fact that Jan is offering the Rene Herse bikes with either electronic shifting or the Nivex shifter makes sense to me. I’ve ridden top end mechanical shifting systems from Shimano, Campagnolo, and SRAM. All of them work extremely well when new. In fact, before riding the Rene Herse my next bike was going to be a wide-tired all-road bike with mechanical shifters and hydraulic disc brakes. However, I feel there are two reasons not to offer conventional mechanical shifting systems on the complete Rene Herse bikes. First, I think the designs of many of those systems are sliding toward the non-repairable, planned obsolescence that characterizes many modern consumer goods. Second, I think that if I was choosing against the elegance of the Nivex and Rene Herse shifters, there is every reason to go electronic. One could argue that electronics are a simpler, more elegant user experience than any mechanical shifter. I can’t really refute that argument. The reasons I prefer the Nivex are more aesthetic than practical. I simply don’t want a bike with batteries. I like the purity of a bicycling experience powered exclusively by my own efforts. I also enjoy feeling a fine mechanical system at work. I expect to enjoy that feeling over thousands of miles.”

More information:

- Video showing the front derailleur in action. (There’s also a rear shift, but you don’t see much, since it’s so fast.)

- Bicycle Quarterly 75 featured a performance comparison between the Rene Herse and the OPEN MIN.D.

- Ordering page for 80th Anniversary Rene Herse bikes and frames. Order will start on August 15, 2021.