The Technical Trials

The Technical Trials are best known for the incredibly light bicycles that constructeurs built in the 1940s. (The 1946 Alex Singer above weighs a little over 17 pounds fully equipped.) More importantly, the Trials advanced bicycle technology by serving as a test bed for new bikes and components.

Low-trail geometries, braze-ons for all components, front derailleurs, low-rider racks, aluminum fenders, wide and supple 650B tires, aluminum cranks, cantilever brakes, sealed-bearing hub and bottom brackets, even aluminum frames: Almost everything we like in bicycles today proved its worth during the Technical Trials of the 1930s and 1940s.* These innovations did not come from racing, but were used first on cyclotouring bikes.

The laboratory for French cyclotouring bikes were the Technical Trials. What were the Trials? Simply put, they were competitions for the best bicycle, rather than the best rider. The Trials were started by a group of riders from Paris, who were loosely organized in the Groupe Montagnard Parisien.

These riders were dissatisfied with the bicycles available in the early 1930s. The heavy mass-produced machines of the time had many features, but were lacking in performance and handling. The riders from the Groupe Montagnard Parisien (GMP) envisioned lightweight bicycles with precise handling, excellent performance and utmost reliability.

In 1934, the GMP organized their first Concours de Machines (Technical Trials): an event where bicycles were judged based on features such as light weight, number of gears, etc. The rules required certain geometries (<50 mm trail, relatively short chainstays), wide tires (>35 mm) and braze-ons for all accessories. To stand a chance at winning, the bikes had to be much lighter than was the norm. “It can’t be done, superlight bikes would never hold up in everyday use,” said the many detractors.

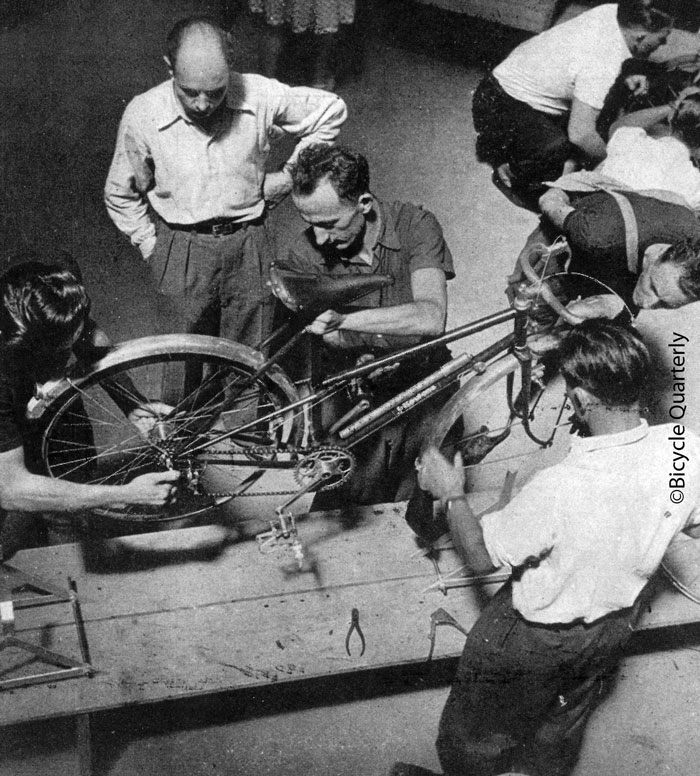

To show that such bikes could hold up under the harshest “real-world” conditions imaginable, each bike was ridden over 460 km of rough gravel roads in the mountains of the Massif Central. This ride was done in three stages, and after each stage, the bikes were checked carefully for defects (below).

Penalties were assessed for any problem, whether a wheel was out of true, a bearing had developed play, or a derailleur no longer could shift every gear. After three days of hard riding, the winner was the bike which offered the best combination of:

- most desirable features

- lightest weight

- fewest problems on the road

The result was truly amazing: At a time when most cyclotouring bikes weighed 20 kg (44 lb.) or more, the winning Barra weighed just 10.35 kg (22.8 lb.), fully equipped with fenders, lights, a rack and wide tires. Keep in mind that this was 1934. This is lighter than any of the current bikes that Bicycle Quarterly has tested.

Not only did the Trials prove that the GMP’s vision for lightweight, high-performance cyclotouring bikes was achievable, but the event also provided an opportunity for a new breed of builders to showcase their talents.

Builders like Reyhand, Barra and Uldry had tried to make racing bikes before, but with the big manufacturers sponsoring professional teams, they found it hard to sell their machines. The Technical Trials provided an opportunity to prove their worth without investing much money. A builder could make an excellent bike, have it ridden by a good rider, and their efforts would be noticed by a nation-wide audience of riders. (It’s a situation similar to today, where most young builders make cyclotouring bikes again, rather than trying to compete with the big names in the racing bike market.)

Progress was swift during the 1930s. Not only did the bikes become lighter, but they also suffered fewer problems on the road. The undisputed leader in the 1930s was Reyhand, who won the Trials three times in a row (above: the winning bike from 1936).

The bikes were ridden by the strongest randonneurs of the time: You got extra points for high speeds, because riding fast stresses the bike more. Among these pilotes were riders who soon would set up shop under their own names: Alex Singer, René Herse, Jo Routens, Lionel Brans, René André and others. Most of these builders then used the Trials to make their own names.

After World War II, little time was lost, and the next Technical Trials were held in 1946. Alex Singer won this event with the ligthest cyclotouring bike ever built. This machine weighed just 6.875 kg (15.16 lb) – without the tires. Quality tires were available only on the black market, so the bikes were weighed without tires. An Alex Singer bicycle from the 1946 Trials has been preserved, and is shown in the Japanese Alex Singer book (top of this post).

In 1947, it was René Herse’s turn to win the event. One of his bikes also still exists (above). It is featured in our book The Golden Age of Handbuilt Bicycles.

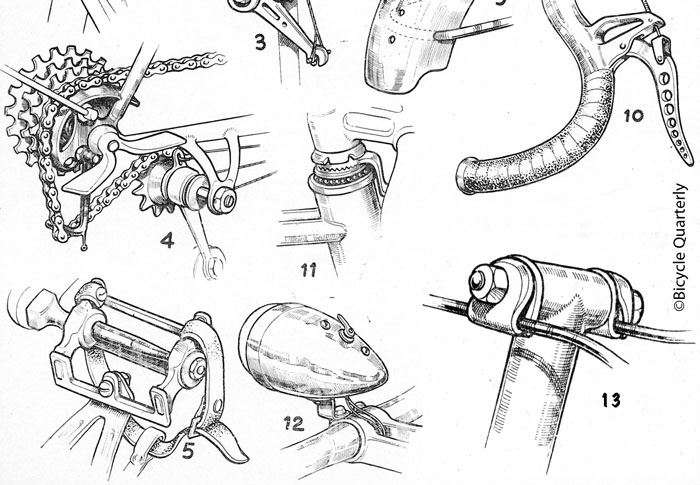

Daniel Rebour documented the amazing features of these machines. Every part was modified to reduce the weight. Alex Singer even cut away the pedal bodies (No. 5 above), exposing the spindle.

The Technical Trials consisted of only nine major events (and a few smaller ones in the Paris area), spanning just 15 years. It was an amazing time, when every year saw huge progress. The high hopes of the constructeurs were either rewarded or dashed on the road. The list of the names who won the Technical Trials reads like a Who’s Who of the best constructeurs of the time: Barra, Reyhand (3x), Narcisse (2x), Alex Singer, René Herse, Jo Routens.

The technical innovations that proved their worth in these difficult events are still with us today: aluminum cranks, sealed cartridge bearings in hubs and bottom brackets, low-rider front racks, powerful cantilever brakes… The Concours de Machines were a resounding success, and their influence still is felt more than 60 years later.

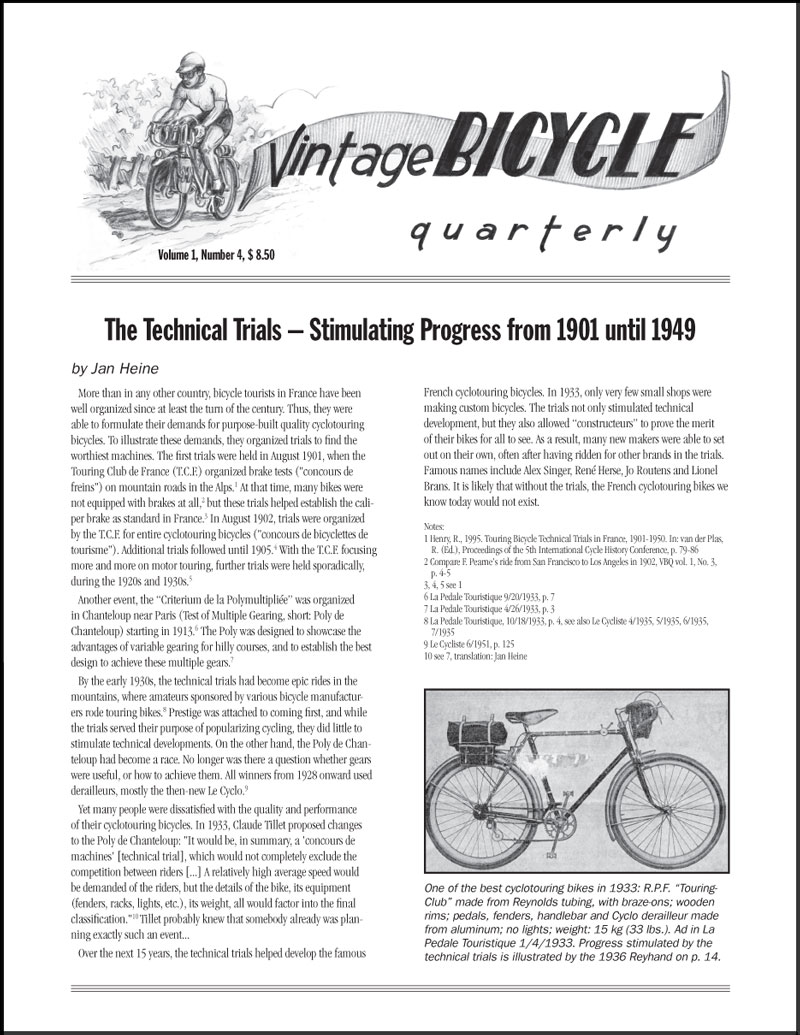

The story of the Technical Trials was told in two consecutive issue of Bicycle Quarterly: Vol. 1, No. 4 and Vol. 2, No. 1, with details of each year’s Technical Trials. Photos bring you the atmosphere of these events. Result sheets allow you to find out who won and why. Translated reports from participants and spectators make a gripping read. More than 90 drawings by Daniel Rebour show the intricate details of the machines that competed for the title of “the best bicycle.” To find out how the bikes we enjoy so much today were developed, order your copies here.

* Some of these innovations were offered earlier, but had not become widespread, either because the technology did not yet exist (modern aluminum alloys) or because no one promoted these innovations.