Gravel is as old as cycling!

When the project for a Gravel Cycling Hall of Fame was announced, there was immediately some pushback: Isn’t ‘gravel’ too new to have a Hall of Fame? From the perspective of gravel racing, that makes sense. Many of the big names from the early days of ‘gravel’ are still racing today. The legitimacy of a Hall of Fame rests on a measured approach. Before honoring somebody, you’d want to consider their entire careers over space and time. But is ‘gravel’ really such a new thing?

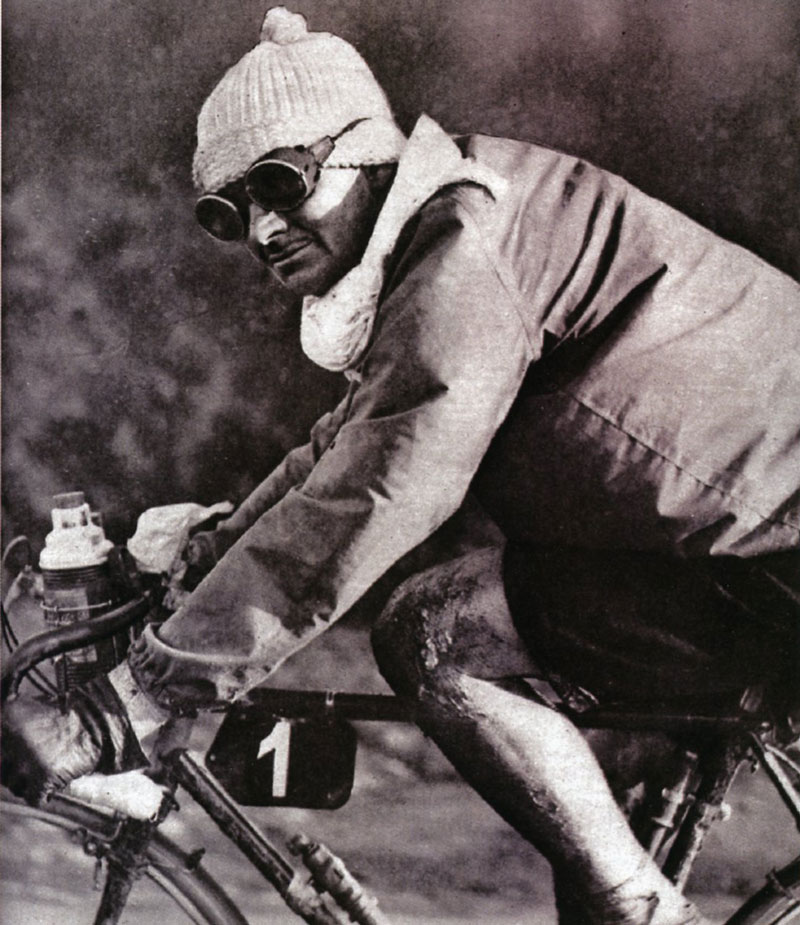

Riding on gravel is as old as cycling itself – in the 19th century, there simply weren’t any paved roads outside the cities yet! In fact, some of the first overland paved roads were built to make bicycle riding easier and more comfortable. Were those early cyclists – above Hubert Opperman at the 1931 Paris-Brest-Paris – gravel riders?

I don’t think so. Riders like Opperman or Fausto Coppi may have won their most important victories on gravel roads, but they wouldn’t have considered themselves ‘gravel racers.’ They were racers, plain and simple, and it was just a coincidence that the most epic roads were not yet paved back then. It’s reasonable to say that the spirit of ‘gravel’ is riding on loose surfaces even though you could ride on pavement.

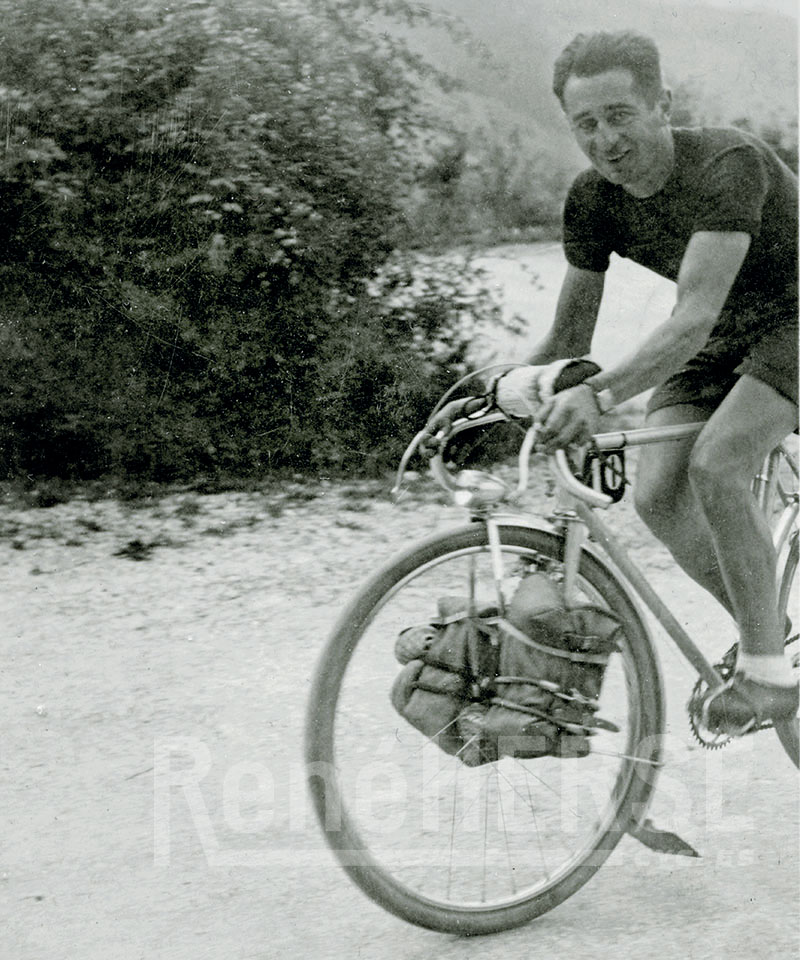

That brings us to the mid-century riders who sought out lonesome mountain passes even though paved roads were plentiful in France. René Herse (above) and Paulette Porthault (top photo) could have stayed on highways, but they chose to explore unpaved mountain passes all over Europe. Were they the first ‘gravel cyclists’? Maybe, although it seems that gravel wasn’t their objective – they just wanted to explore beautiful places by bike.

There were also the cyclo muletiers – riders like the famous builder Jo Routens and his brother Marcel (above) who rode on little paths in the mountains because of the challenges they provided. But their rides were more like mountain biking on singletrack, not gravel riding as we know it today.

That brings us to the early mountain bikers. The famous Repack Road in Marin County was – and still is – a gravel road. What if Gary Fisher and Charlie Kelly had called their company GravelBikes instead of MountainBikes? Would history have taken a different turn?

The early mountain bikes didn’t look like gravel bikes – above is Joe Breeze on one of the original Klunkers. That didn’t take long to change, though, as road bikes began to influence mountain bikes. Joe Breeze built the first purpose-built mountain bike frames with extra tubes inspired by heavy-duty touring bikes, but he soon realized that these reinforcements weren’t needed. Charlie Cunningham and Jacquie Phelan also came from a road background, and they rode their road bikes on the gravel trails of Marin County.

Charlie started to build mountain bikes, and Jacquie (above) raced them with great success. To the modern eye, those early Cunninghams look like gravel bikes – rigid frames with 43 mm-wide tires and drop handlebars. In fact, Charlie and Jacquie told me that other brands used flat handlebars mostly because the industry wanted to sell mountains bikes as ‘new’ and ‘relaxed.’ Drop handlebars were associated with the uncomfortable ‘Ten-Speeds’ left over from the 1970s bike boom that everybody still had in their garages. The industry saw flat bars as essential to promoting the new ‘Mountain Bikes.’ Jacquie’s three NORBA championships certainly showed that drop bars were well-suited to the early mountain bike races. The courses of those races look like gravel roads, too. Does that mean that gravel riding is just a return to the roots of mountain biking? There is a lot to be said for that.

From their ‘gravel’ origins, mountain bikes evolved to handle more extreme terrain. This made them less suitable for riding long-distance rides on gravel roads. That left a void for riders who just wanted to explore off the beaten path. By the early 2000s, that void was felt on both coasts. There were rumors that a few lonesome riders had been exploring gravel roads in the Cascade Mountains on cyclocross and mountain bikes, but their exploits had largely passed unnoticed.

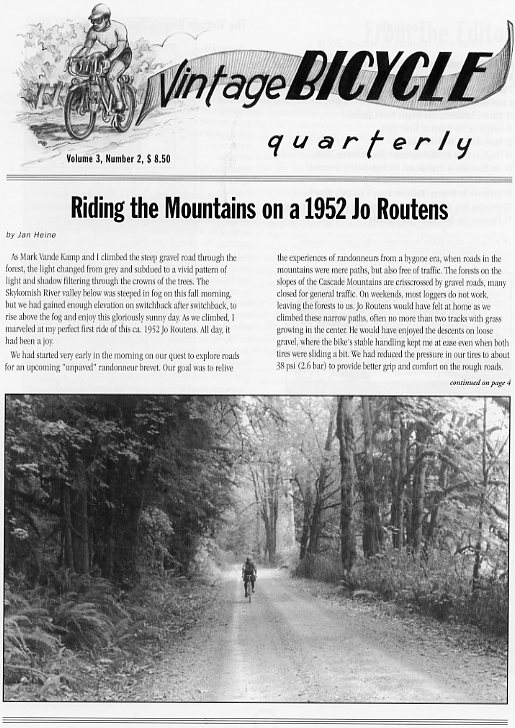

Inspired by the stories and photos of mid-century French cyclotourists, we began to search for unpaved routes in the Cascades and wrote about our rides in Bicycle Quarterly (above the Winter 2004 edition). In 2005, we organized a 100 km Unpaved Brevet. The same year, Sandy Whittlesea ran the first D2R2 – Deerfield Dirt Road Randonnee – the famous gravel ride in western Massachussets. The names ‘dirt’ and ‘un-paved’ show that ‘gravel’ had not yet emerged as a genre of cycling. Dirty Kanza, the event that became Unbound, started a year later – with just 34 participants. (We had almost as many at our Unpaved Brevet.)

Did we invent something new when we started riding on gravel? I don’t think so – after all, my first ‘gravel’ bike was a 1952 Jo Routens built for the same roads that the mid-century French riders enjoyed. At the time, we felt we were rediscovering something beautiful rather than inventing something new.

As riding off pavement became popular, people were looking for a catchy phrase to describe this ‘new’ sport. The alliteration ‘gravel grinding’ became popular, but many riders resisted the new term: Our goal was to float over the gravel rather than grind through it. As tires became wider, ‘grinding’ fell by the wayside, and riding on unpaved surfaces became simply ‘gravel riding.’

What about gravel racing? Was the 2006 Dirty Kanza the first gravel race? Actually, gravel racing in North America is much older than even mountain biking. It started with attempts to replicate the feel of the famous Paris-Roubaix. America doesn’t have cobblestones like northern France, but we do have gravel. Most of these early gravel races included ‘Roubaix’ in their names – a clear sign where the inspiration came from. Some of these races still exist; the Barry Roubaix in Michigan is perhaps the most famous.

Locally, we had the Spokane River Roubaix – which I raced way back in the 1990s with my college cycling team (above). We all entered the race on our road bikes, with 21.5 mm tubular tires! We were definitely ‘grinding’ through the loose gravel back then. I remember it was epic, but not that much fun – simply because we didn’t have bikes suitable for gravel yet.

The popularity of ‘gravel’ has gone hand in hand with the development of gravel bikes. The early gravel events saw riders on cyclocross bikes, touring bikes with knobby tires, mountain bikes, and even some mid-century French bikes like my Jo Routens. That’s changed completely – today there’s a vast selection of purpose-built gravel and all-road bikes for all tastes and riding styles. In fact, wider tires have migrated to road bikes, too. Back when ‘gravel grinding’ started to be a thing, riders discussed whether 25 or 28 mm tires were best for riding on gravel. Some mavericks went as wide as 32 mm. Today, that’s a discussion road cyclists have about the perfect tires for pavement – the positive influence of gravel on cycling in general is undeniable.

The long history of ‘gravel’ shows that the lure of riding off the beaten path has always been strong. ‘Gravel’ is really a state of mind, a return to the roots of cycling, when every ride was an adventure, and before cycling was split into ever-smaller categories. Gravel today is road cycling, cyclocross, mountain biking, cyclotouring, randonneuring and more, all wrapped into one vibrant and exciting sport. Gravel can be a bikepacking overnighter into the hills with friends. It can be Unbound, where the winners average 20 mph for ten hours. Or it can be the Tour Divide, a race where the record stands at just under two weeks. As a style of riding that transcends categories and definitions, perhaps gravel doesn’t really need a Hall of Fame.

Photo credits: Charles Porthault (Photo 1); Gordon Bainbridge (Photo 6); Ansel Dickey (Photo 10)