Fully Integrated Design

Car drivers are lucky: They can buy sports cars that are fully equipped to be driven in the rain and even at night. And their fenders rarely rattle loose, their lights don’t fall off, and most car owners think little of driving 1200 km without having to tighten bolts or do other maintenance. The secret to this reliability and performance is a fully integrated design.

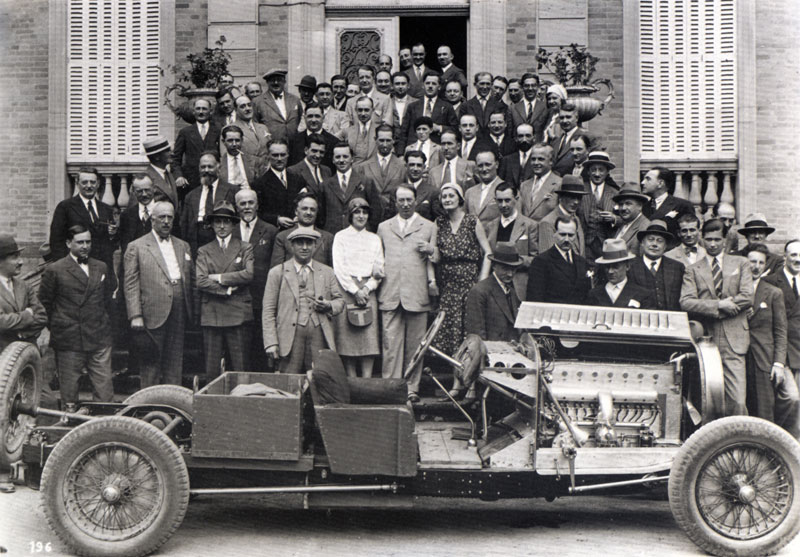

It wasn’t always like that. In the early days of the automobile, car makers provided just the chassis. Below is a brand-new Bugatti sports car ready for delivery.

Of course, the owner didn’t drive it like that, but took it to a body builder, where a body and all the other accessories were added. The owner got to choose the body style, the fender shape, lights and many other details. The resulting cars could be breathtakingly beautiful and elegant.

For the time, they offered great performance, too. Equipped with a 3.3 liter compressor engine, this Bugatti Type 57 could go 180 km/h (112 mph), and few cars could keep up with it on the open road during the late 1930s.

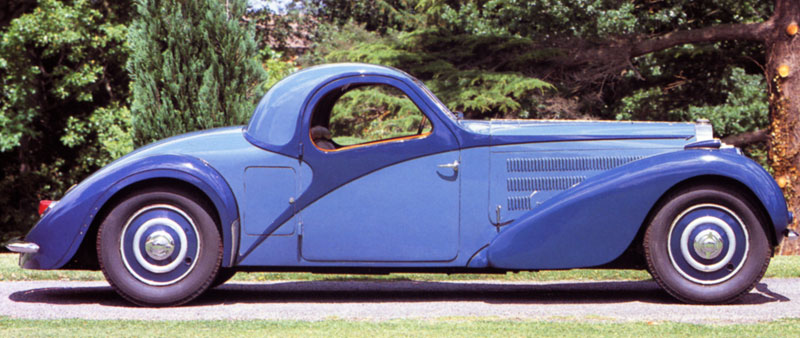

Fast forward 12 years, and suddenly you had a new breed of sports cars with smaller engines and much fewer horsepower that were not just able to keep up with the Bugatti, but outperform it with ease on a curving road.

What had happened? The Lancia above no longer used a separate chassis, but featured unibody construction. The body was the load-bearing structure. The fenders were integral to the design, and so were the lights. Not only was this structure lighter and more rigid, but it also greatly improved the reliability of the car. Gone were the days when fenders rattled loose, lights vibrated until their bulbs broke, and bodies cracked because they flexed independently of the chassis. Everything was conceived as a unit, everything worked together, and the result was a car with modern performance.

In the bike world, we are still stuck in the 1930s. If you buy a “real-world” performance bike at most bike stores, you get the equivalent of a rolling chassis, whether it’s a cyclocross, a touring or a “randonneur” bike. Here is an example:

The manufacturer expects you to add the various parts you need to make the suitable for real-world riding. The result usually looks something like this:

This bike has all the drawbacks of a 1930s cars and then some: The many clamps and adjustable sliders add a lot of weight. They are likely to come loose. You are bound to get rattles and resonances from the fenders. Lighting wires are zip-tied to the outside of the frame, where they are vulnerable. And the resulting bike doesn’t even look as elegant as a 1930s Bugatti. No wonder many cyclists prefer to ride just the rolling chassis, rather than deal with all the clamped-on “accessories.”

Now imagine a bike where all the parts you need have been integrated into the original design. For a loaded touring bike, it would look something like this bike from our book The Golden Age of Handbuilt Bicycles (as always, click on the photo for a more detailed view):

The racks are custom-made for the frame. They fit exactly, with no adjustments necessary or even possible. That makes them lighter and above all stiffer, which improves the handling of the bike. It also means that they are unlikely to need tightening – ever. The fenders attach directly to the frame, without spacers or tabs, providing a more solid attachment that is unlikely to flex, resonate or crack. The lights are integrated into the rack (front) and fender (rear).

In the photo at the top of the post, you see a detail of such a fully integrated bike. Note how the fender attaches directly to the frame, with a reinforcement at the spot where the stresses are greatest. See the remote control lever for the generator, so you don’t need to stop if you want to turn on the lights. The fender has a small bulge to make room for the generator’s wheel. The lighting wires run inside the fenders and frame. This is not only prettier, but also reduces the risk of the wires getting snagged and broken.

The result is a lighter, stronger, more reliable and more elegant bike. It also offers better performance. It’s the bicycle equivalent of a modern car. Once you have experienced a fully integrated bicycle, it is hard to go back to the equivalent of a 1930s car.