Why you should wear a helmet — but not insist that others wear one

Update 12/2025: This post was written in 2014. Fortunately, the discussion about helmets has moved on since then, and ‘helmet wars’ seem to be a thing of the past. In Seattle and many other places, mmandatory helmet laws have been repealed, yet helmet usage remains at a very high level. Below are the reasons why it makes sense to wear a helmet yourself, but we should not insist that others wear helmets.

In the U.S., most ‘responsible’ cyclists wear helmets, yet when I cycle in Europe or Japan, I see many cyclotourists who ride without helmets. The Europeans or Japanese don’t seem like dare-devils or poorly informed. What is going on here? I’ve thought about this a lot, and I’ve concluded that helmets don’t matter all that much, compared to other factors that that influence the safety of cycling. Wearing a helmet is a good idea, but focusing on helmets can distract from what’s more important: learning to ride safely and improving safety by making drivers aware of cyclists.

Please note that I am not anti-helmet. When I was in college in Germany, I was one of two cyclists in town who wore a helmet. Apart from the two of us, no cyclist wore a helmet back then. (We bonded over our helmets and became friends.)

I’ve worn a helmet on most rides since then. Even so, I have revised my views on this topic – while continuing to wear a helmet.

As an individual cyclist, safety comes from being able to control your bike and from being able to anticipate other traffic’s often erratic moves. On a societal level, safety comes from having so many cyclists on the road that cycling is normal and accepted.

A helmet is only the last line of defense when everything else fails. That’s why cyclists should wear one. However, insisting that others wear helmets is counterproductive on a societal level: It discourages cycling by making it seem more dangerous than it is, and it distracts from focusing on the skills to avoid accidents.

What about the arguments in the ‘helmet wars’? Let’s look at them one by one:

1. Helmets can prevent or reduce injuries in many typical accidents.

This is true. A helmet is likely to reduce your injuries in many typical crashes, and it rarely seems to do any harm. There may be instances where the helmet’s larger size (compared to a bare head) increases the forces on the rider’s neck, but they seem to be rare.

However, helmets cannot protect against severe impacts. Unlike modern safety systems in cars (seatbelts, crumble zones, airbags), helmets don’t make most accidents ‘survivable.’ Thus, priority should always be given to avoiding accidents, with a helmet only as the last (and imperfect) defense if all else fails.

A reader pointed out that a bright-colored helmet can make the rider more visible—a useful contribution to avoiding accidents in first place.

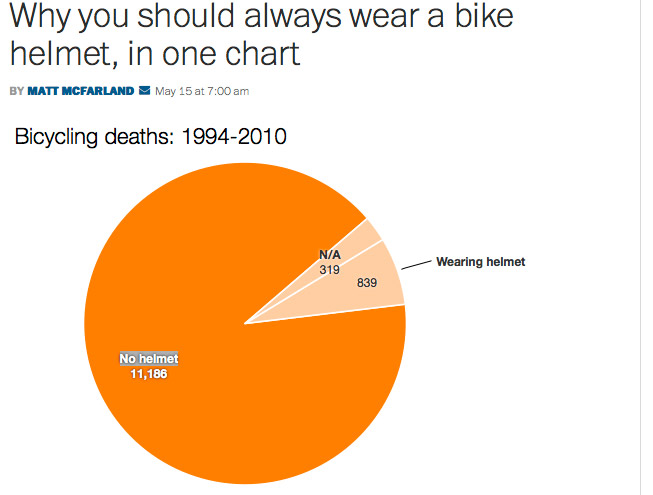

2. Most cyclists who died didn’t wear helmets (used as proof that helmets save lives).

This is misleading, because it assumes that riders who wear helmets and those who don’t wear helmets otherwise behave identically. They don’t.

Consider that 25% of cycling fatalities occur between 9 p.m. and 6 a.m. Most people who are getting killed aren’t randonneurs on night-time rides. They were people who lost their driver’s license because of drunk driving. (31% of cycling fatalities have blood alcohol levels of 0.08 or higher.) These fatalities occur on their way home from the bar. Most of these riders don’t wear helmets, but they also are riding a bicycle while intoxicated, without lights, usually on busy highways, just after the bars close. The lack of helmets is their smallest problem.

So these statistics can be misleading. The good news for us is that the statistics also overestimate the dangers of cycling. If you do not ride drunk, without lights, after midnight, on busy highways, then you already have reduced your accident risk significantly.

To figure out how effective helmets really are, you’d need a randomized trial, where you assign riders randomly to wear helmets or not each day they ride. The riders shouldn’t know whether they are wearing a helmet, so you’d give the “no-helmet” riders a placebo – something that looks like a helmet, but doesn’t protect your head. Of course, you wouldn’t do a trial where you potentially put riders in harm’s way, so this is a non-starter.

Another way to assess the value of helmets is to compare statistics from one country to the next. Sweden and Denmark used to be great examples: The Swedish wore helmets, the Danes did not. Both countries kept good accident statistics that provided useful data. Despite wearing helmets, Swedish cyclists had roughly the same rate of head injuries as Danish cyclists.

Conclusion: Helmet use doesn’t seem to have a great impact on overall cyclist fatality rates.

3. Helmets make cycling appear more dangerous than it is.

This is true. In the U.S., when I part with people and get on my bike, many say: “Be safe!” or “Be careful out there!” I don’t get that in France, where people encourage me with “Pedalez bien!” (Ride well!)

When I drive a car or walk, nobody says “Be safe!” Modern cars are equipped with airbags, so you don’t have a wear a helmet while driving. It would be cheaper and safer to wear helmets – race cars don’t have airbags, yet are much safer than the cars we drive on the road. But helmets would reinforce the message that you are about to engage in a dangerous activity, whereas airbags are invisible until you need them…

In reality, cycling becomes safer if more people ride. Cycling in Copenhagen is relatively safe not because the cyclists there are more skilled. Nor do the cyclepaths reduce the risk of accidents. (They don’t.) Even though cyclist in Copenhagen don’t wear helmets, cycling is safe there because everybody is used to looking for cyclists.

Furthermore, if everybody cycles, drivers no longer harbor resentments against cyclists for their presumed political views and social preferences. In the U.S., much of the animosity against cyclists stems from what people perceive cyclists to stand for – city dwellers, liberals, granola-crunchers – rather than from the minor inconvenience they may cause on the road. (Few people get irate when a farm tractor slows them down for a few seconds before they can safely pass.)

Conclusion: Emphasizing helmets discourages people from cycling, which makes cycling less safe.

4. Helmets provide a false sense of security, therefore people feel they can take more risks.

This does not appear to be true. Yes, more cyclists die in countries where riders wear helmets (U.S., UK) than in countries where cyclists ride bare-headed (Europe). At first sight, it may seem plausible that the helmets themselves somehow make cycling less safe. The best hypothesis seemed to be that riders who wear helmets feel invulnerable and take greater risks. The technical term for this is ‘risk compensation.’

The data do not support this analysis. In the U.S., most riders who die don’t wear helmets (see 1), so the higher death rate in the U.S. cannot be explained by risk compensation of helmet-wearers. In fact, helmets take the ‘carefree’ out of cycling and make people more aware of the risks (see 3.).

A more likely explanation is that American and British cyclists wear helmets because cycling is more dangerous there. Fewer people cycle, and there’s a perception that bicycles don’t belong on roads.

In a round-about way, a focus on helmets can make cycling less safe: If we tell new cyclists that a helmet is all they need to guarantee their safety, we are putting them in harm’s way. Real safety comes from accident avoidance through looking ahead, anticipating others’ behavior, and judging the road conditions correctly.

We may see the same in cars, where we North Americans tend to focus on buying big cars with the best safety ratings, but sometimes don’t focus as much on learning to drive well. And our traffic fatalities are among the highest in the industrialized world, much higher than in countries where people drive small (and relatively unsafe) cars with greater skill.

And before you wonder, I’m not taking any risks in the photo above: I’m riding well within my capabilities and those of my bike and tires.

Conclusion: As a society, a focus on helmets detracts from teaching about real safety.

So where does all that leave us? From my perspective, there are two conclusions:

- On an individual level, wearing a helmet is a good idea. It is likely to reduce your injuries in many typical crashes, and it rarely seems to do any harm.

- On a societal level, insisting on helmets is detrimental. It detracts from the facts that a) cycling is relatively safe, and b) that real safety comes from preventing accidents more than from trying to survive them.

Wear a helmet if you are an ‘optimizer’ – the type who worries about the last 5% in performance or safety. (I do wear a helmet!) But don’t tell anybody else to wear one, or not to wear one! Instead, let’s focus on teaching cycling and traffic skills.

What about the tandem photo at the top of the post: When I asked Lyli Herse, the daughter of our founder, whether she had a special wish for her 85th birthday, she replied: “I’d like to ride one more lap of the course of the Poly de Chanteloup hillclimb race.” Riding with various tandem partners, Lyli had won that prestigious race no fewer than 8 times in the late 1940s and 1950s. However, an 85-year-old lady who hadn’t ridden outdoors in years heading into traffic on a hilly course didn’t seem like a good idea. Which logically led to the idea of riding a tandem together. We found an old René Herse tandem, and Lyli set to training as she would have in the old days, except she was riding on her home trainer now. With more than 5,000 km of preparation, she was amazingly strong. The tandem climbed the 14% hill of Chanteloup with ease, and only my friend Christophe, a former amateur racer, could keep up with us!

Why no helmets? Lyli had never worn a helmet (apart from the leather hairnets during her racing days), and me wearing one when she was unprotected didn’t seem right. Most of all, for an 85-year-old woman, any fall would be disastrous. So the order of the day was simply: Do not take any risks!

Further Reading:

- The history of the Poly de Chanteloup hillclimb race, and the story of the tandem ride with Lyli, were published in Bicycle Quarterly 45.