Myths Debunked: Marginal Gains Are NOT the Best Way to Make Your Bike Faster

‘Marginal gains’ are the latest buzzword in cycling. The idea is that many tiny improvements can add up to make a meaningful difference. Make 10 changes that each save 3 Watts, and you’ll have gained 30 Watts…

Think of Greg LeMond winning the 1989 Tour de France by eight seconds (above)… If the second-placed rider, Laurent Fignon, had used ceramic bearings, he might have won that year.

Chasing these marginal gains, cyclists put bigger pulleys into their derailleurs to reduce the bending of the chain and make other tiny improvements.

Marginal gains may be appealing when you feel that they are all that is left, after you’ve optimized everything else on the bike. And yet most riders still can make major improvements that will outweigh the sum of all the marginal gains. Here are two examples:

- Switching to truly fast tires gives you the biggest edge. We are talking 5% in speed gain when compared to most racing tires – and much more if you currently ride stiff gravel or touring tires.

- Getting a frame that ‘planes’ and gets in tune with your pedal stroke can increase your power output by 5% or more.

Even Greg LeMond won the ’89 Tour not because of marginal gains, but because his aerobars reduced his wind resistance by at least 10% compared to Fignon’s traditional bike.

Aerodynamics enable you to go faster without spending any money: Get into the aero tuck on downhills, and you’ll reduce your air resistance by about 30%. Not only will you go faster on the downhill, but you’ll coast further on the flat (or up the next hill), before your speed drops back to where pedaling is faster than coasting. Coasting more allows you to pedal harder the rest of the time. This is one of the secrets behind riding fast across rolling terrain.

There are other gains that we may consider marginal, but each will make a bigger difference than just a few Watts:

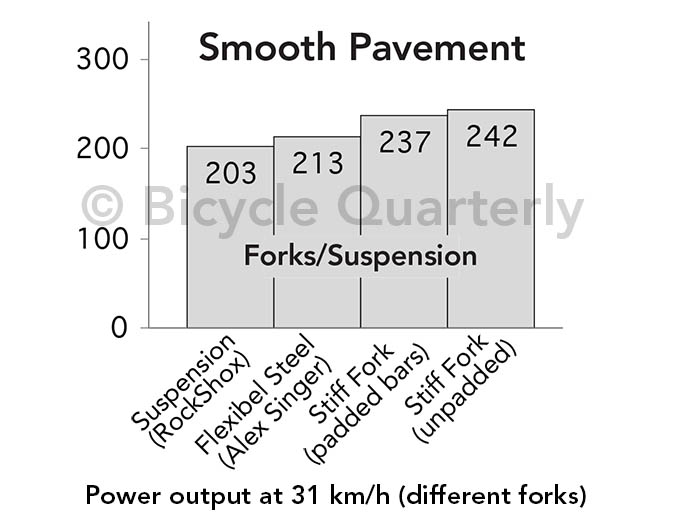

- A fork that absorbs ‘road buzz’ can save 20-30 Watts on smooth roads by reducing the suspension losses, yet most modern forks are stiff and absorb little shock (above).

- Wide handlebars increase our air resistance. Some pros use ultra-narrow bars, but even going from 44 to 42 cm bars will make a difference.

- When we optimize the aero tuck, our knees touch the top tube. Modern frames have wide top tubes, which means that our knees can’t get as close together. Modern cranks put our feet further outward. Both increase our frontal area. It’s probably the reason why BQ’s carbon test bikes descend slower in the aero tuck than our randonneur bikes.

- Cogs smaller than 14 teeth significantly increase a drivetrain’s resistance, because the upper chain run is under load. By comparison, there is almost no load on the lower chain run, so the savings from extra-large derailleur pulleys are much smaller.

Combining all these small, but significant, gains does make a difference. They are the reason why our fully equipped randonneur bikes are as fast (or faster) than modern carbon bikes on real roads, even though the carbon bikes are a bit lighter.

There is one place where very small gains matter: the weight of the bike. Because a bike consists of so many parts, the way to make a lightweight bike is to reduce the weight of every part as much as possible. The remarkably light weight of the J. P. Weigle for the Concours de Machines (above) – 20 lb (9.07 kg) fully equipped – did not come from a few superlight parts, but from every part being as light as possible without giving up strength. Does it matter? Well, every bit counts!

If you are interested in how bikes really work, you’ll enjoy our book The All-Road Bike Revolution. It includes all the research that has changed cycling in recent years. Find out why wide tires can be fast, how to find a frame that optimizes your power output, and how to get a bike that handles like an extension of your body. More information is here.

Photo credit: Nicolas Joly (Photo 6).