The Best Drivers' Cars are 50 Years Old

Quite a few people were surprised at the 2017 Concours de Machines when Peter Weigle’s bike was the lightest by a big margin. With a steel frame and mostly metal components, the Weigle weighed just 9.1 kg (20.0 lb) fully equipped with wide tires, fenders, lights, a rack, even a pump and a bell. To date, no carbon or titanium bike has been as light, while being similarly outfitted for real adventures.

As impressive as that weight was, for the Concours, being light was not enough. In this competition for the best “real-world” bike, the contestants were ridden over hundreds of miles on very challenging courses, including rough mountain bike trails, with more than 5,000 m (16,000 ft) of elevation gain over two days. Not only did they get penalized if something broke, but they also had to perform well. Any bike that didn’t maintain a high average speed incurred further penalties.

The Weigle was one of the fastest bikes in the event, bettered only by bikes that were ridden by strong amateur racers whose power output gave them an advantage. How can this bike be so light and perform so well, when, at least on the surface, it lacks the latest technology?

Car enthusiasts probably aren’t surprised. Ask ten motoring journalists which cars are the best to drive, and they won’t point to the the latest carbon-fiber supercars, though they are amazing technological achievements. Instead, the best driving machines trace their roots 50 years back, but they have been honed to the nth degree by small, dedicated companies.

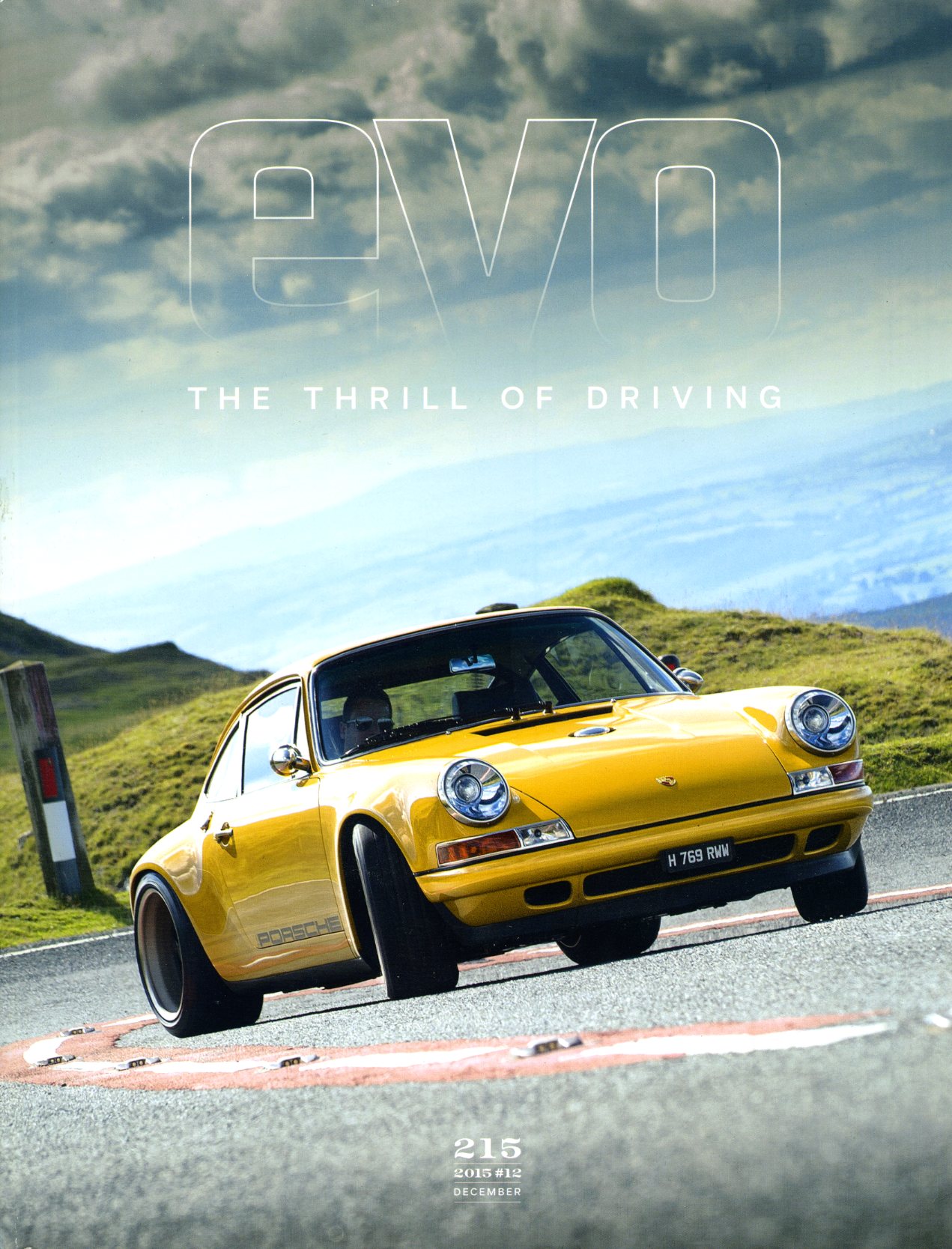

Top of the current crop is a Porsche “reimagined by Singer”. This small Californian company takes air-cooled Porsche 911 – 25-year-old cars built to a design introduced in 1962 – and replaces almost every part with a hand-made component that is outwardly similar, but has been improved in every way possible. The price tag for these “used cars” starts at $ 350,000. And everybody who has driven one says it’s worth the money. That is reflected in the two-year wait list if you want one. (I’d love to experience driving one!)

If you just care about the driving, and don’t need things like a roof or a trunk, the Caterham 7 is supposed to be even more amazing. For me, the most surprising part is that this is a car introduced in 1957 (as the Lotus 7)! You have to be an expert to distinguish the latest model from one made decades ago, but the Caterham also has been refined, with new engines, modern tires, and numerous other tweaks. And yet the basic concept is the same as it was 60 years ago. On paper, it’s archaic, but in practice, it is said to offer a performance that belies its age.

On a ride with the BQ Team, we talked about these cars and wondered: How can they be better to drive than the latest supercars? On paper, it looks like a Lamborghini Aventador should be the far better car. It’s developed by a huge engineering team and made in an advanced carbon fiber production facility. How can small companies like Singer and Caterham, that most people haven’t even heard of, make cars that are better to drive?

I think there are a few reasons for this:

- Refining the same design over many years allows small manufacturers to make each car better than the last. The big makers have to introduce new products all the time. Then they spend the first few years ironing out the bugs. Once the product approaches maturity, it’s time for the next model.

- The cars from the small makers sell to an educated clientele, so they don’t have to play the “numbers game”. They can give up a little in horsepower, 0-60 times and top speed to focus on what really matters: performance and enjoyment on real roads.

- Without large overheads and the need to compete on price, every part can be the best in the world. For example, the Singer Porsche’s shock absorbers cost more than some brand-new cars. Small makers can choose a part that is 10% better, but costs 30% more, knowing that their customers will appreciate it. For big companies, it’s more cost-effective to spend that money on marketing, and keep their per-unit costs low.

- These factors outweigh the small advantages that modern materials may offer in theory.

There is a direct parallel between these cars and randonneur bikes like the Weigle or my René Herse (above). Like that Porsche or the Caterham, they may look like classics, but they, too, have benefitted from decades of development. Every part has been refined until these bikes offer a performance that is hard to match. “Modern” mass-produced bikes may be lighter, stiffer or have more gears – impressive “numbers” – but none offer superior performance across real-world terrain.

With so many beautifully designed and meticulously crafted details, it’s easy to overlook that these bikes are great to ride. Or as a journalist put it about the Singer Porsches: “They may be engineered to perfection, but they’re also engineered to be fun.”

If you are in the Boston area, you can see Peter Weigle’s amazing Concours bike at the New England Builders’ Ball this weekend, on Saturday, Sept. 23, 2017.

And the full story of the 2017 Concours de Machines is in the Autumn 2017 Bicycle Quarterly, including an article by Peter Weigle on building the bike and going to France for the Concours.

Photo credits: evo magazine (Photo 1), Natsuko Hirose (Photo 3), Caterham (Photo 4), Maindru (Photo 5).