The Science of Tire Tread

Tread patterns are the most noticeable part of a tire, yet there seems to be little agreement of what makes a good tire tread. With road tires, some are completely slick. Others have small scallops or longitudinal lines. Off-road, some tires have knobs that are round, others are square, or angled like Vs. There are large and small knobs, or a mixture of both. Gravel tires for fast riding tend to have smaller knobs, but nobody explains why. (Smaller knobs flex more, so you’d think they absorb more energy and make the tire slower.)

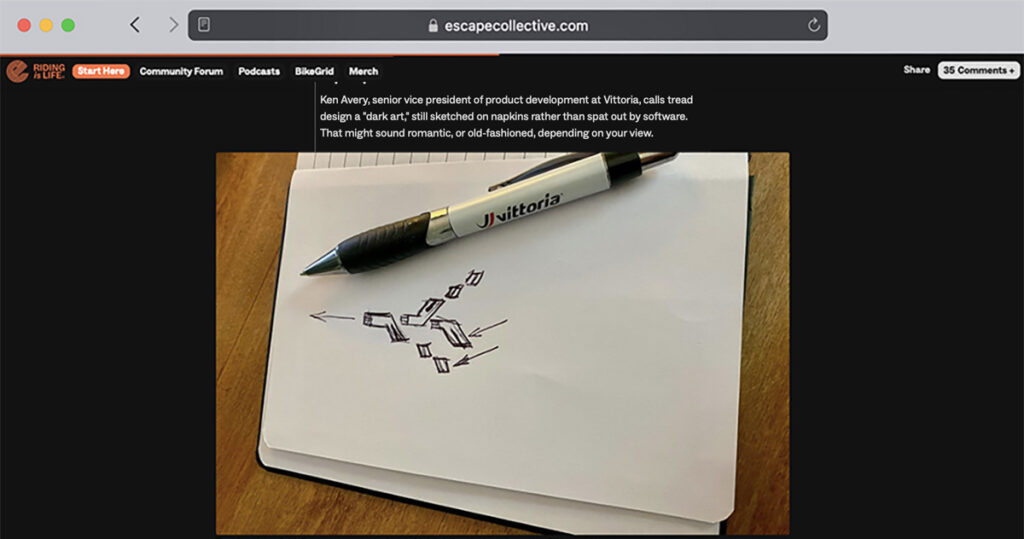

Recently, the Escape Collective published an article about tire tread design. In the story, Vittoria’s senior vice president of product development explains that “tread design is a ‘dark art,’ still sketched on napkins.” We read that “Continental’s philosophy is to create a tread pattern that visually conveys the terrain it is intended for.” In other words, the tread pattern is more about looks than performance. That matches my experience: The engineers from another big tire maker once told me that “tread patterns are more about design than function.”

Back then, the comment from the engineers made think that there must be a better way. After all, tire tread is where the forces of pedaling, cornering and braking are transmitted to the road surface. The forces that occur at the road / tire interface can be measured, simulated and calculated. We know how rubber deforms. There’s a lot of potential for science, yet tire companies still handle these questions with sketches on napkins?

As with most Rene Herse products, we created our tires because nobody made what we needed for our own rides and adventures. We wanted wide tires that offered superior performance. Supple casings are one piece of puzzle. Just as important are optimized tire treads.

Road Tires

Most road tires are essentially slicks. At some point, tire makers realized that customers like to see some tread pattern, so they added little scallops or other intermittent designs to the tread. As the above-mentioned tire engineers explained, the goal is to give slick tires a more interesting look, not to enhance performance.

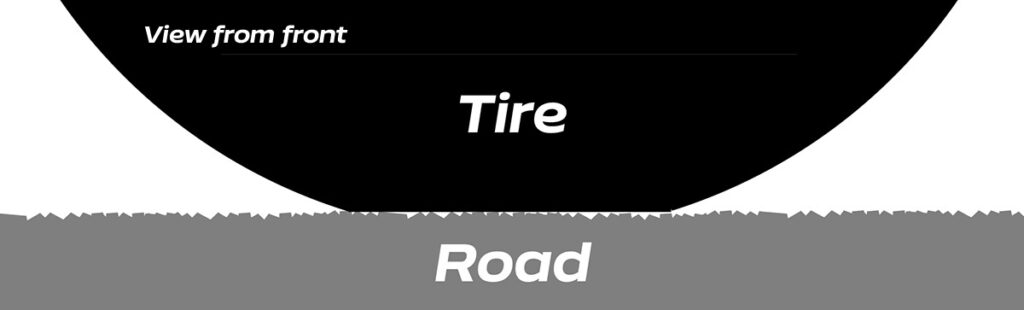

To get a better idea of how tire and road surface interact, let’s look at a tire (from the front), while the bike is cornering. What keeps the bike from sliding out? Obviously, it’s the grip of the tire on the road surface. The more grip our tires have, the faster (and safer) we can corner.

Physics tells us that friction is greatest between smooth bodies. From that perspective, a slick tire seems to make sense. Except pavement isn’t smooth, but made up of small stones that are embedded in the asphalt.

Way back in 1988, Mathew Aaron, a tire engineer at Michelin, published an article in Bike Tech titled: “The Importance of Real-World Results.” He explained that “tire rubber conforms to the road surface and creates multiple interlocking mechanical connections with the pavement.” In fact, road surfaces are designed with a certain amount of ‘bite’ to increase this interlocking pattern. The irony is that Michelin was making slick tires back then. Did the article reflect the frustrations of an engineer who knew better, but was overruled by the marketing department?

It’s easy to visualize how important this interlocking is. If tires did not interlock with the road surface, grip would be determined by friction between tire rubber and asphalt alone. When the surfaces are wet, the coefficient of friction is dramatically lower. If friction was the only factor, wet-weather grip would only be a fraction of dry grip. We all know that’s not true: On wet roads—unless the surface is ‘greasy’—cyclists can corner at about 70-80% of their dry-road cornering speeds. Much of this traction comes from interlocking between tire and road.

Of course, slick tires also interlock with the road surface, because the hard road surface digs (a little) into the soft rubber of the tire. Could a well-designed tread pattern improve the interlocking of tire and road, as suggested by the Michelin engineer?

My experience supports this idea: Slick tires don’t grip as well as tires with tread. Way back, before we made our Rene Herse tires, we used the Grand Bois Hetre on our rando bikes. The Hetre was the first wide tire with a reasonably supple casing. However, its tread pattern was inspired by old French tires, with thick longitudinal ribs that weren’t ideal for performance.

Peter Weigle, the famous builder and good friend, developed a technique for shaving off those ribs. This created a slick tire with a supple casing. Peter’s ‘shaved Hetres’ were lighter and noticeably faster than the standard model. Back then, shaved Hetres were prized possessions. If you had a pair, you stored them carefully in a dark, dry place. You put them on for special events and took them off immediately afterward.

I mounted a set of shaved Hetres for the Raid Pyrénéen. This epic 720-km route traverses the Pyrenees Mountains, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea. During the descent from the first mountain pass, on a wet road, my front tire suddenly lost grip. This came as a total surprise: I had ridden my bike—with standard, ribbed Hetre tires—for many miles in all conditions, and I knew how much grip they usually had in the wet. Thankfully, I wasn’t badly injured in the fall, and I continued my ride for another 35 hours. (My bloodied knee is conveniently hidden by the water bottle in the photo above, taken on the last of the 18 cols.)

It was a wonderful ride, but I was surprised by the lack of grip of the slick ‘shaved’ tires compared to the ribbed standard model. A little later, I had another, similar experience, also on slick tires.

That got me thinking: How can we maximize the interlocking between tire and road? Pavement is made up of irregular little stones. If the tire has many little edges, some will interlock with these road irregularities. More edges allow for more interlocking. Obviously, the edges need to be stiff enough, so they don’t just fold over when they push against the road irregularities. How stiff they need to be, and how much rubber we need, is something we can calculate.

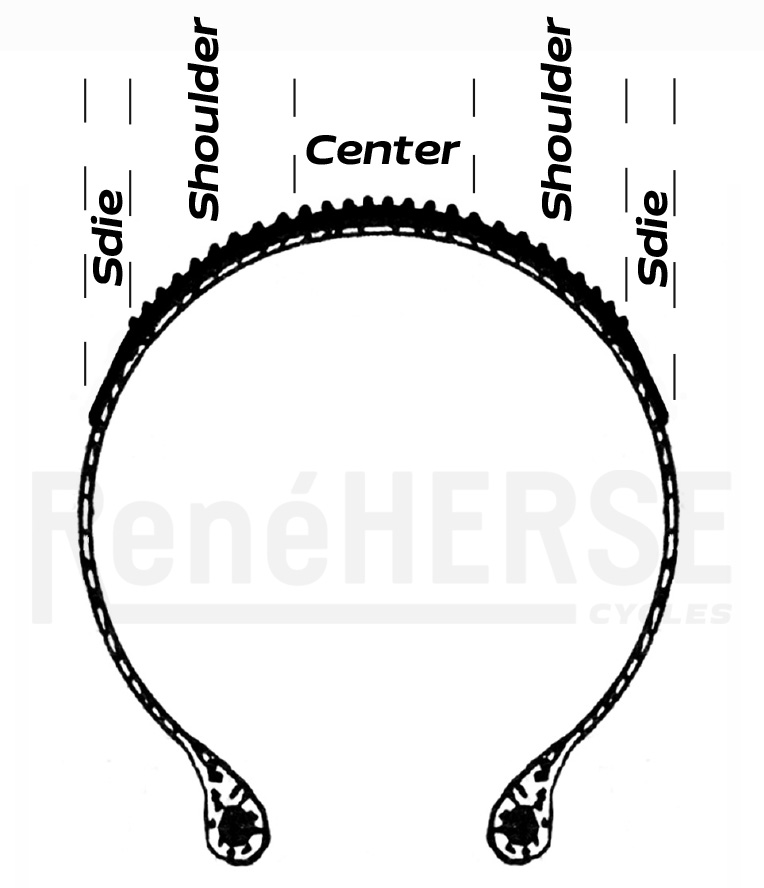

Here is how that looks in practice: As the bike leans into the turn, the tire rolls on its ‘shoulders.’ Ribs provide edges that interlock with the pavement. Two sets of ribs run at an angle, to increase their stiffness.

Other parts of the tread have other functions. Further down the tire, on the ‘sides,’ the tread never touches the road. (You can’t lean that far!) Here, we only need a thin layer of rubber to protect the casing against cuts. The tread in this area can (and should) be slick.

When we’re going straight, the tire rolls on its center section. On pavement, straight-line traction isn’t a problem, so no interlocking is needed. The center of the tread is the only part that sees significant wear, so we added small longitudinal ribs that act as wear indicators.

We also made that the center of the tread a little thicker, since that’s where the tire wears down as you ride. This doubles the mileage you’ll get out of your tires. Here is how this works: A tire is worn out when you get down to the last millimeter of tread. That means a 2 mm-thick tread can lose only 1 mm until it’s worn out. A 3 mm-thick tread can wear down 2 mm—twice as much. The extra millimeter of rubber weighs just a few grams and doesn’t affecting the tire’s speed. (We’ve tested this.)

As you can see, Rene Herse tread design is based on a thorough analysis of each portion of the tread and what it needs to do. That’s how science works.

When we received the first prototypes of our Rene Herse tires, I replaced the Hetres on my bike. The next morning, I headed to the gym, still sleepy at this early hour. On familiar, empty streets, I was riding on auto-pilot. When I turned onto a side street at the bottom of a long hill, my front wheel almost hit the curb on the inside of the corner. My bike was turning much tighter than it usually did, because the tread was interlocking more with the road surface.

This interlocking is (almost) independent of temperature and moisture. It’s makes the biggest difference when friction is low: on cold and/or wet surfaces. In the 12 years since we introduced our tires with their optimized tread pattern, I haven’t lost grip once. I don’t ride any slower than before—if anything, I’m probably descending faster, now that I can really trust my tires…

Knobby Tires

Knobby tires are an extreme example of interlocking between tire and ground. When the ground is soft and slippery, the coefficient of friction is almost zero. Slick tires just spin without finding any traction. Now the ground is softer than the tire, and knobs can dig into the soft surface and create those ‘interlocking mechanical connections.’

For traction in mud and snow, all you need are tall knobs and plenty of open space in between. Wide knob spacing is important so the tread doesn’t clog: You need clean knobs that bite into the surface when they rotate to the bottom again.

The knob shape itself is secondary. In the past, some of the best ‘cross tubulars had round knobs. They worked fine in most conditions. In very soft mud, round knobs are a bit too streamlined, and the mud can flow around them. Square knobs provide more resistance. More complex knob shapes just add more places for mud to get stuck. That’s why Rene Herse knobbies have square or rectangular knobs, with rounded corners to reduce the ability of mud to stick.

Making a knobby that works great in mud is easy, but ‘cross courses (and gravel routes) usually include some pavement, too. And that’s where traditional knobbies show their limitations. For many years, I raced ‘cross on Super Mud tubulars. I loved the speed and comfort of their ultra-supple casings, but I was always bothered that they rode so poorly on blacktop. Just when I really wanted to accelerate, the small knobs were folding over and holding me back.

We tested other knobbies and semi-slicks, and they were no better. When we were on pavement, existing knobby tires were buzzy and slow. When we leaned the bike into (paved) corners, the tires suddenly climbed onto the edge of a row of knobs and broke away without warning. Off-pavement, when it got muddy, tires with small, closely-spaced knobs just clogged up and lost all traction. We might as well have been riding slicks at that point.

We kept thinking: “There must be a better way!” What if we applied science to the problem? What if we don’t add knobs to the tire surface, but start out with a slick tire? Then carve away the tread, but retain enough of the original surface to keep the characteristics of the slick tire? That’s how car tires are made. Above are the tires for Formula 1 racing. On the right, you see two wet-weather tires.

The Formula 1 rain tire is essentially a knobby. The tread blocks are very large, since they have to transmit huge horsepower, but they are knobbies nonetheless.

Formula 1 race cars have 1000 horsepower. Even pro cyclists rarely exceed two horsepower. (2 hp = 1,491 watts!) With so much less power flexing the tread blocks, we can make the knobs much smaller.

How small? Can we make them so small that they act like knobbies—without losing the rolling characteristics of the slick tire we started out with?

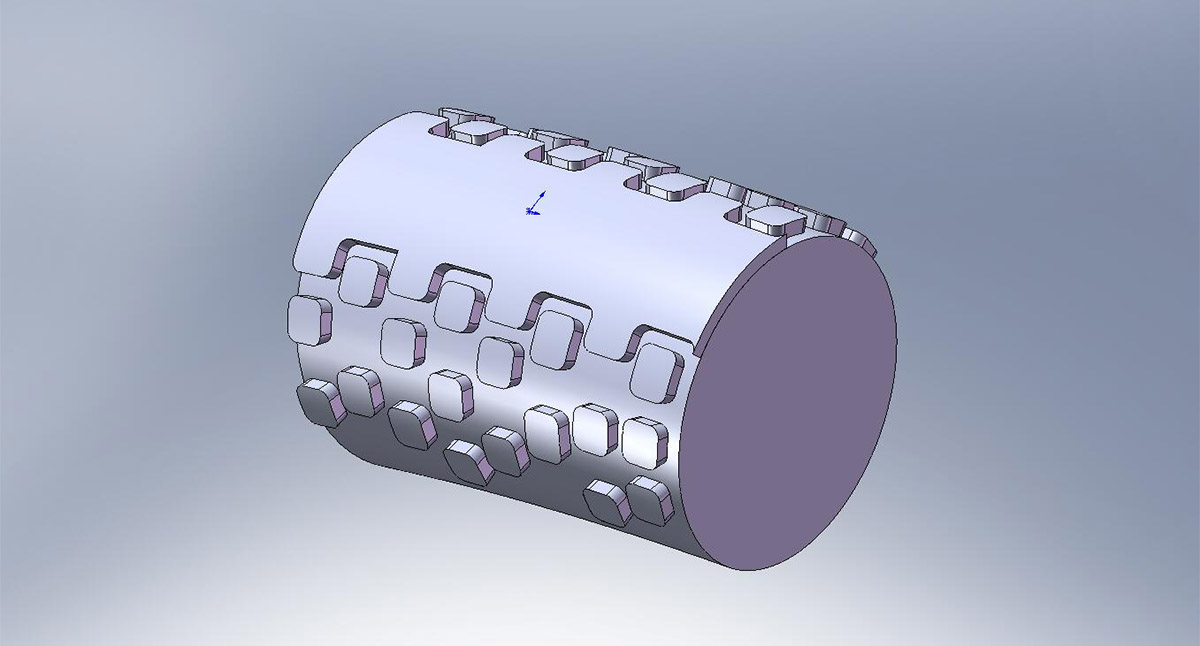

Rather than sketch knobs, we modeled the negative space between the knobs. We calculated how much rubber we needed to maintain the qualities of a slick. That gave us a minimum size for the knobs. Any smaller, we’d lose the qualities of the slick.

Then we checked if those knobs were small enough to dig into loose surfaces. And whether we had enough space between the knobs so they would not clog with mud and self-clean at speed. We were excited when we realized that our idea should work.

Creating a knobby tire by removing material from a slick was a completely new idea. The little animation above shows how it works: Start with a smooth tire and carve away. Leave rubber in strategic places, so the original slick surface remains. In the end, you have a knobby tire, but the knobs are actually remnants of the original slick surface.

On pavement, the tire rolls on the original slick surface. On loose surfaces, the knobs dig into the ground for extra traction. That’s why we call these tires dual-purpose knobbies: They ride like a slick on pavement and grip like a knobby on dirt, mud and snow.

(Of course, we don’t actually make tires by carving up slicks. Our production tires are made in molds that create the final tread pattern from the get-go.)

Does this actually work? Calculations and models are good, but the proof is on the (gravel) road. As soon as we got the first prototypes of our new tires, we went testing. In mud and snow, the large knobs dug into the soft surface and provided outstanding grip. They spacing was large enough that they didn’t clog with mud, but left a clean imprint.

The real test came on pavement. Here the Rene Herse knobbies really did corner like slicks. The big knobs didn’t fold or flex—just as we had calculated. The edges of the knobs work like the ribs of our all-road tires: They interlock with the road surface.

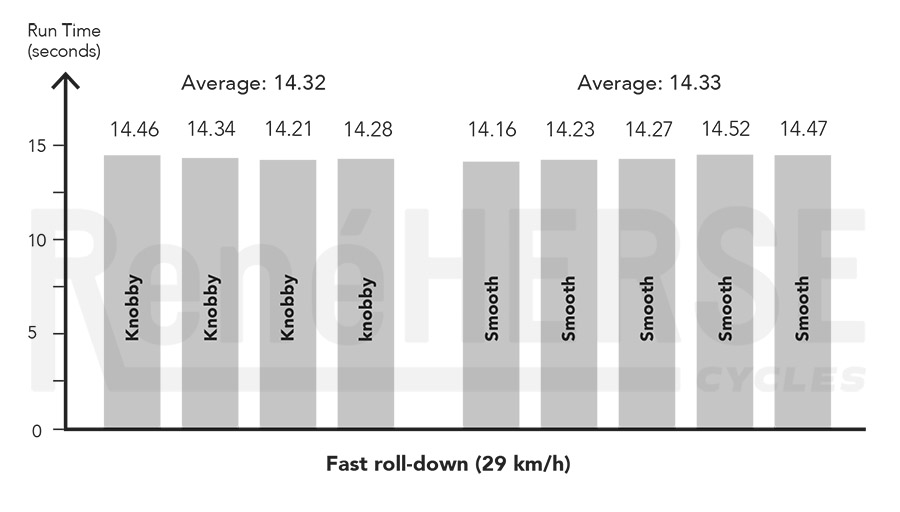

We also tested the speed of our new knobby tires. They roll as fast as our smooth all-road tires. The graph above shows back-to-back test runs with our knobbies and smooth tires, both in 44 mm width. The smooth Snoqualmie Pass is among the world’s fastest tires, yet the knobby doesn’t roll any slower.

We always run multiple test runs to make sure there are no issues with other variables, like wind, rider position and temperature. If we get consistent results, we can trust our measurements. Our roll-down tests measure all factors that determine a tire’s speed, not just rolling resistance. We expected a little more wind resistance with the knobs, but even at 29 km/h (18 mph), this wasn’t a factor.

The test above is just one of many. We’ve confirmed the results with roll-down tests at high and low speeds, as well as tests with power meters. Time and again, our knobbies have shown the same speed as our smooth tires. That’s why we’re confident in the results.

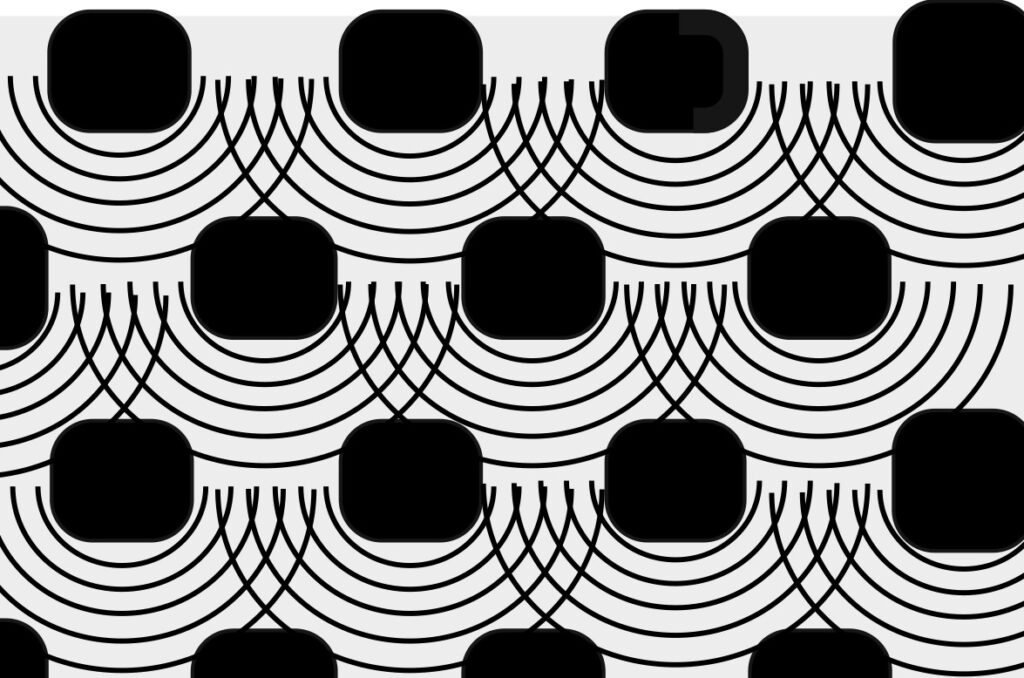

Now we had knobbies that rolled and cornered like slicks, but they still had one drawback: the buzzy noise typical of knobby tires. That noise is generated when the sharp edges of the knobs hit the road. If an entire row of knobs hits the pavement at once, the frequencies can overlap and reinforce each other—that’s why some knobbies are even buzzier than others.

That got us thinking: What if we move the knobs around so they don’t all hit the ground at the same time. Could we stagger them so their frequencies no longer reinforce each other, but cancel each other out? That’s how noise canceling works.

It took a lot of computing to figure out the best knob locations for the typical speed range of bicycles. Would it really work? You can imagine our excitement when we tested the first prototypes: They were much quieter than other knobbies.

The 29″ x 2.2″ Fleecer Ridges were the first to feature our noise canceling. They won the prestigious Design & Innovation Award. The reviewers found the Fleecers to be “noticeably quieter than comparable tires.” They also mentioned that “the Rene Herse tires generate masses of traction both off-road and on asphalt when cornering.”

The Fleecers also were named ‘Gear of the Year’ by bikepacking.com. Their verdict: “extraordinarily fast rolling, tough and they grip well.” They also reported that the Fleecers were “remarkably quiet compared to other tires in their class.”

Having independent testers confirm our own results was great. But the tires still had to prove themselves in the ultimate test: gravel and bikepacking races.

We didn’t have to wait long: Our dual-purpose knobbies quickly became the go-to tires for some of the fastest gravel racers and bikepackers. Almost every prestigious race has been won on Rene Herse tires, from Unbound XL to the Silk Road Mountain Race, and (almost) everything in between.

We didn’t rest on those laurels. We kept testing and measuring. We found that, at very high power outputs, our knobs did flex a bit and lost a little power. Most of us don’t put out 500 watts or more, but tall, powerful racers like Ted King and Brennan Wertz do, especially during attacks. For them, the knobbies could be improved.

The obvious solution was a tire with a slick center to eliminate that flex. But conventional semi-slicks often combine the worst of slicks (not much traction on loose surfaces) with the worst of knobbies (unpredictable break-away when cornering). Could we make a new kind of semi-slick? A tire that sprints like a slick, without giving up the great cornering grip and loose-surface traction of our knobbies?

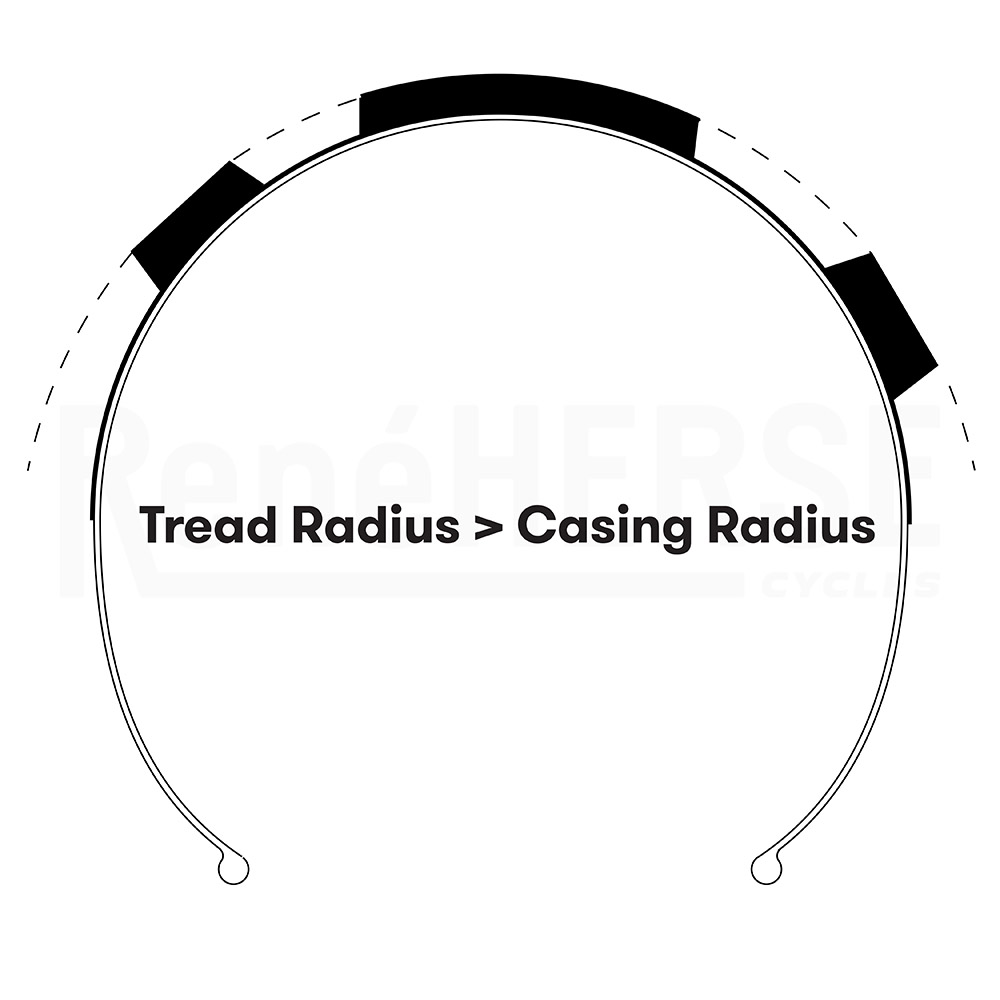

At first sight, it might seem easy to use our method of carving away a slick tire to create a semi-slick: simply leave the center portion of the slick tire untouched. But it’s not that easy! To grip well, knobs have to be tall, and so we start our knobbies with a thick tread. We don’t want that much rubber in the center of a semi-slick. It would make the tire heavy, stiff and slow—not what we wanted. And if we eliminate the knobs in the tire’s center, their frequencies aren’t available for the noise canceling any longer.

The solution? We made the radius of the tread significantly larger than that of the casing. That way, we get a thin center tread without compromising the grip of the tall side knobs. We also keep the round cross-section that essential for predictable cornering. And we rearranged the knobs, so the noise canceling works again.

Racers often sprint out of the saddle, rocking their bikes from side to side. How could we increase traction and reduce resistance when the bike is leaned over—while going in a straight line?

We’ve anchored the first row of side knobs on the center tread. That makes them stiffer, for more traction and less flex under high power outputs. The stiffer knobs also help with power transfer when the tire hooks up on loose surfaces.

Once you see how the side knobs are anchored on the slick tread, it’s totally obvious. But somebody had to come up with the idea… And since we filed for a patent, it’s not like you’re going to see this feature on other tires anytime soon.

We only introduced our semi-slicks a year ago, yet they’ve already won races and set FKTs on the most demanding courses. We’re getting a lot of requests for our new semi-slicks in more sizes. Currently we offer the 700C x 44 Corkscrew Climb and the 700C x 48 Poteau Mountain.

They may look similar, but each size is a completely new tire with a completely different tread pattern. We can’t just scale up the knobs—their size is determined by physical properties of mud and other loose surfaces. Just adding more knobs in random places also doesn’t work, because the noise canceling requires the knobs to interact in precise ways.

Developing a new size takes significant resources and time. We’re working on expanding our line, but this won’t happen overnight. The good news is that our smooth all-road tires and our dual-purpose knobbies are already available in a wide range of sizes.

That’s the story of our tire treads. As much as we appreciate the romance of sketching tread patterns on napkins, we feel that a scientific approach yields better results. That’s why our tires look different from other road and gravel tires. Each part of the tread is there for a reason, based on calculations and modeling to bring out the best performance. When you ride them, you feel the difference.

More Information:

- Rene Herse tires

- Our book The All-Road Bike Revolution presents all the results of our research in a fun, easy-to-read format.

Photo credits: Continental (slick tire); Pirelli & C. S.p.A (Formula 1 tires); Ansel Dickey (Ted at Unbound); Marc Arjol Rodriguez (velophoto.tx; semi-slick in action); Jim Merithew (@tinyblackbox; Brennan winning)