When the Tour de France Charged Admission

The recent furor around ‘privatizing’ the last kilometers of famous mountain stages in the Tour de France, and charging admission, has died down a bit. For now, those ideas have been dismissed by Tour organizers… In all those discussions of how free viewing is an essential part of the Tour de France, one small, but important detail has been overlooked: Charging admission to stage finishes in the Tour is not a new idea—that’s how it was done for many years. In the early days of the Tour, the public had to pay to see each day’s final sprint.

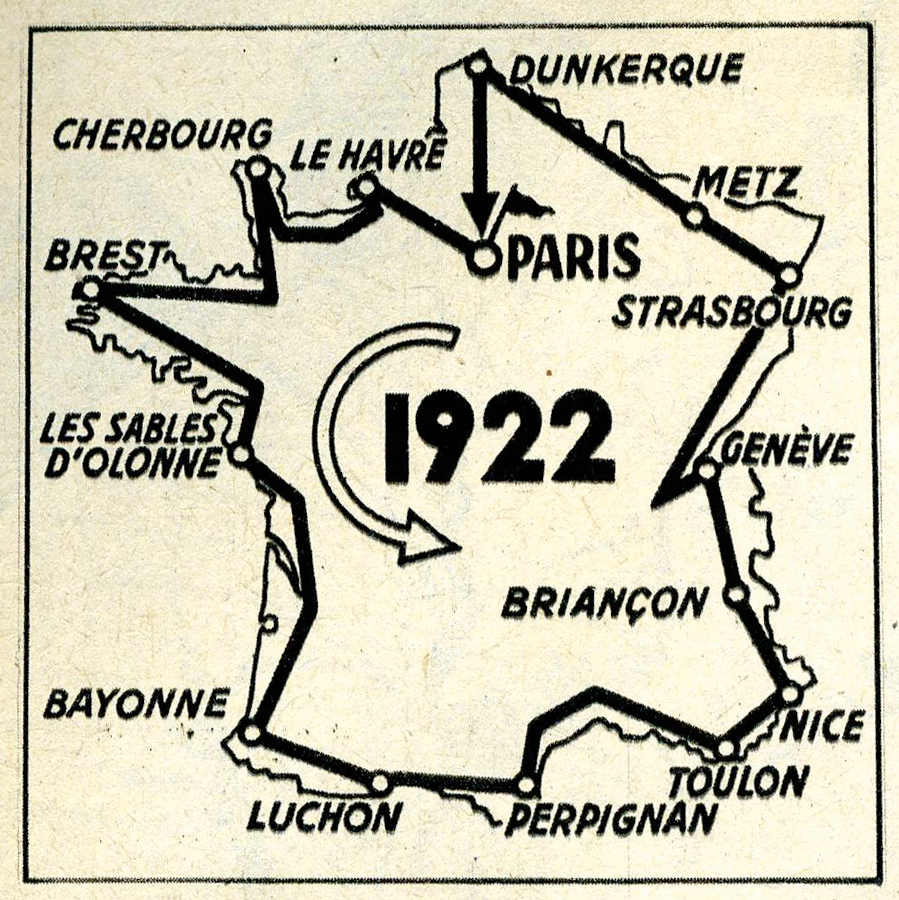

For the first 50 years, the Tour had a more-or-less set route, which went around the perimeter of France—a true ‘Tour of France.’ The Grande Boucle (‘Big Loop’) was run either clockwise or counter-clockwise, but the actual stage finishes rarely changed. There was a reason for that: The stages had to finish in velodromes, so the organizers could charge admission.

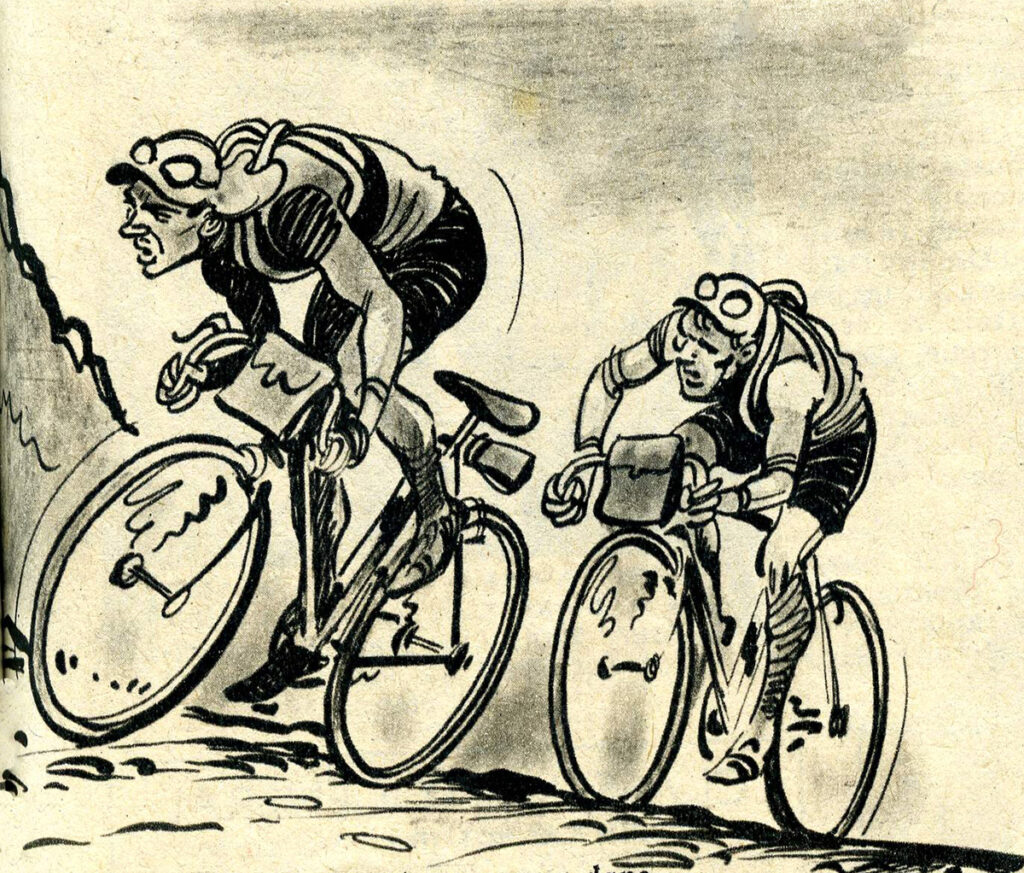

Today, Paris-Roubaix is the only big road race that still finishes in a velodrome. What makes Paris-Roubaix special these days—cobblestones and the finish on the track—were once commonplace in French bicycle racing. During the heroic age, as the Tour de France made its way around the country, at the end of most stages, racers emerged from a tunnel under the bleachers, turned sharply onto the track, and then launched their sprint on the oval banking. Thousands of spectators watched. And to get into the velodrome, those spectators paid for their tickets. That was the real reason to finish in the velodrome: There was an infrastructure already in place to accommodate large numbers of paying spectators. (Today Paris-Roubaix no longer charges admission to the general public.)

Why did they charge admission back in the day? Well, the Tour de France has always been a business. The initial idea behind the Tour was to promote a new magazine, L’Auto. Even though the magazine was financed by the car and bike industry, the race at least had to cover its costs. And so was born the practice of charging towns for ending a Tour stage there. That still continues today. Nowadays, towns and cities pay to raise their profile nationally and internationally, hoping to attract tourists, business investments, etc. Back then, the calculation was simpler: A town with a velodrome could sell tickets to watch the finish, and hopefully turn a profit.

Of course, spectators didn’t just pay to see the racers ride one or two laps in their final sprint. Before the Tour arrived, there were other track races to warm up the crowd. Celebrities performed. It was a spectacle. In those days, even the fastest randonneurs of Paris-Brest-Paris were paraded around the Parc des Princes velodrome in Paris a few days after finishing their long ride, during a track race. Above, the tandems of Routens/Jouffrey (Jo Routens) and Détée/Bulté (René Herse), who had been fastest of all randonneurs in 1956, complete their lap of honor, flowers in hand.

Velodrome finishes fell by the wayside one by one, except for the final stage: Until the 1970s, theTour finished in Paris on the Parc des Princes track. When that velodrome was demolished, the finish moved to the municipal track, the Cipale, for a few more years. Those who’ve witnessed the arrivals of the Tour in those days report a festive atmosphere, with the winners of the various jerseys parading around the track after the final stage.

Today, the image of the peloton on the Champs Elysées, racing past the Arc de Triomphe, is a symbol of the Tour de France—but that wasn’t always so. Above are Eddy Merckx and his Faema team on the infield of the track, in 1969, after the ‘Cannibal’ won his first Tour.

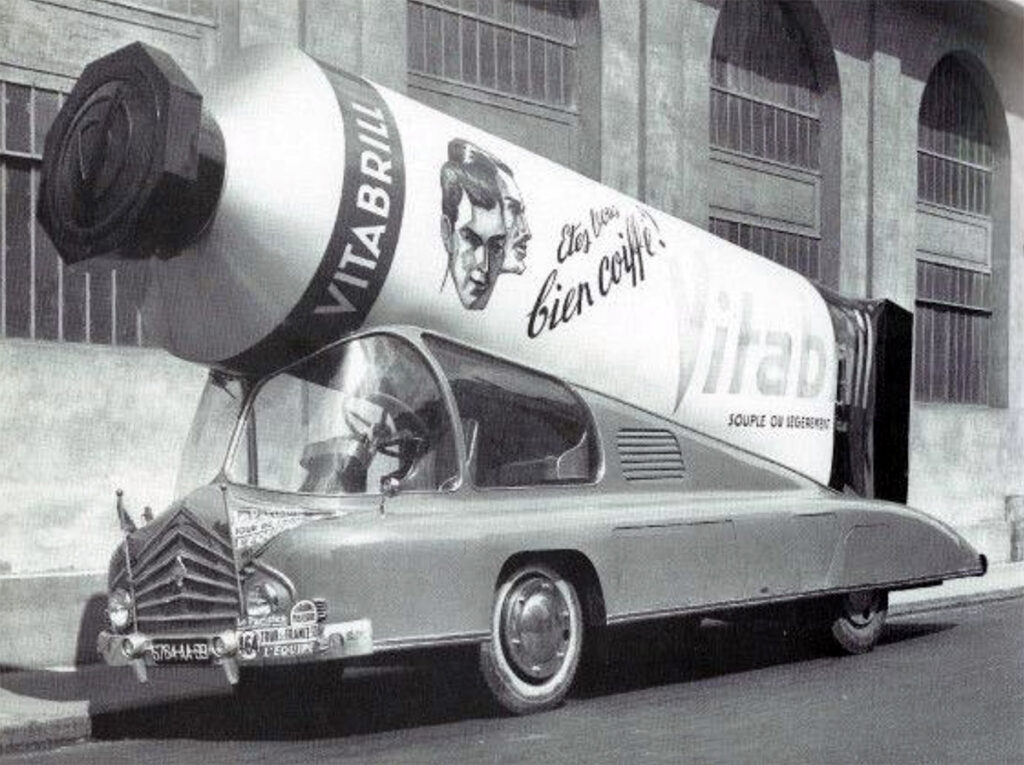

Paying spectators are no longer part of the Tour. The event’s financing model has taken many twists and turns over the years. Take the advertising caravan (sometimes mis-translated as ‘publicity caravan’), for example… Here is how rolling pomade tubes and other eye-catching advertising vehicles came to precede the racers in the Tour: In the late 1920s, founder and organizer Henri Desgrange wanted to break the stranglehold of the pro teams, which back then were run by the big bike makers. He decided to run the Tour for national teams instead. To keep enough spots for all the great French riders, there were regional French teams in addition to the national team, whereas most other nations were allowed one team or, in the case of countries that had few pro cyclists, combined teams. The Tour organizers selected who was on those teams. The national federations were not involved.

The riders in the Tour need mechanics, spare bikes and more. With the big bike makers out of the picture and nobody else involved, Tour organizers had to provide all that—and shoulder the cost. To make up those expenses, the advertising caravan was born: As the Tour passed through towns and villages, it was preceded by cars and trucks that advertised all kinds of things. Back when most people were exposed to relatively few ads, this was undoubtedly effective for those companies and worth paying for.

Back to the velodrome stage finishes… They defined the Tour in more ways than one. Even during mountain stages, the finish was always in a major town—with a velodrome—that was located down in the valley. Until 1952, there were no mountaintop finishes. (Ski areas like l’Alpe d’Huez don’t have velodromes!) Climbers might break away on the slopes, but that was not enough. To win the stage, they had to maintain their advantage during the descent and the—often windy—run down the valley to the finish.

More than one yellow jersey was lost on those long kilometers from the mountaintop to the velodrome. It certainly reduced the chances of winning the Tour for pure climbers. That said, the greatest climbers of the 1950s, Charly Gaul and Fédérico Bahamontès each won a Tour de France (in 1958 and 1959), so it wasn’t impossible.

The Tour switched back to trade teams in 1962… but the advertising caravan continued. It had become a part of the Tour.

The Tour has evolved a lot since those days. Gone is the fixed itinerary. Without the need for a velodrome finish, Tour stages can finish almost anywhere. These days, the Tour route in some years is so convoluted that riders cover more distance during transfer stages than on their bikes.

As the world keeps changing, it’s possible that fewer towns and cities will pay for the privilege of hosting a Tour stage finish. At that point, charging admission for the most iconic parts of the race might be back on the table.

As much as I love the idea of watching the Tour without having to pay, witnessing the finish of an iconic mountain stage already requires a big commitment: You need to show up days in advance, before the roads close, to secure a spot.

A few years ago, I visited Frédéric Charrel, son of the famous mid-century constructeur Paul Charrel, in Grenoble. We rode up the Alpe d’Huez two days before the Tour came that way. The road was already closed for cars, and all the spectators were already there. Camper vans had taken every available spot along the road. Barbecue grills were fired up, music was blaring, children and dogs were running around—it looked like any popular European vacation spot in summer, except there was no beach nearby.

For spectators more interested in the racing than the party, paying a fee may be preferable to having to show up days in advance to secure a spot. For the rest of us, there’ll always be roadside viewing in mid-stage, where the peloton flies by in just a few seconds, but we still get to experience the Tour in all its glory.

We’ll see how the Tour continues to evlove. It’s a fascinating race, and always will be, even as it changes with the times.

Further Reading:

- My adventure of riding around France ahead of the Tour.

- If you enjoyed this article, you might like Bicycle Quarterly, our magazine about the Passion of Cycling.

Photo credits: Xavier Rombouts (Eddy Merckx and Team), Rene Herse Archives (Paris-Brest-Paris 1956), Griffe Photo (Alpe d’Huez).