1952 Rene Herse – Ancestor of Our All-Road Bikes

It’s hard to believe that it was 20 years ago when I first got to experience a 650B all-road bike. The bike in question was a 1952 René Herse Randonneuse. I had been curious about the bikes from the great French constructeurs, but there weren’t many around. And those who collected them treated them as art objects rather than performance bikes to enjoy on the road.

Then I rode my first Paris-Brest-Paris in 1999. At the finish, I met the late Bernard Déon, the historian of PBP, and bought his book about the incredible ride I had just completed. And there I read that riders like Roger Baumann had ridden René Herses through wind and rain in the 1950s, completing the 1200 hilly kilometers (750 miles) in 50 hours or less. As a first-time PBP rider, speeds like those seemed impossible – and they weren’t far behind the fastest riders in modern PBPs.

So when the opportunity came a few months later to sample one of these mid-century bikes, I leaped at it immediately. The bike had seen little use, but storage in an unheated shed had not been kind to the finish: It was a little rusty on the surface. It was a perfect candidate for exploring how these bikes rode: not so precious that riding it hard would deteriorate it, but also not so worn-out that its performance was only a shadow of its former self.

Getting the René Herse to Seattle involved a complex deal that included me traveling to France to pick up the bike, disassemble and pack it at night in a hotel room, and fly back the next day. This is how the adventure started that led to the ‘Wide Tire Revolution’ sweeping across the bike world, and ultimately even to the rebirth of Rene Herse Cycles.

When I reassembled the old Herse, I could already see that it was special. I just had built a state-of-the-art touring bike, but this was something else. Where my pride-and-joy topped 30 lb (13.5 kg) once equipped with rack, fenders and a pump (but no lights), the fully-equipped Herse tipped the scales at just 24.6 lb (11.2 kg) – despite wider tires and a full lighting system.

The way the rack, fenders and lights were integrated into the bike blew my mind. There were no brackets, no sliders, not even any visible wires for the lights. Today, it’s hard to imagine the impact, because this exact-same bike has inspired so many others since then. Bikes like this one are available again from the best of today’s builders.

Some features took longer to discover. When we wondered how René Herse managed to fit 42 mm tires and fenders between narrow-Q cranks and even found room for triple chainrings, we realized that the chainstays were slightly curved.

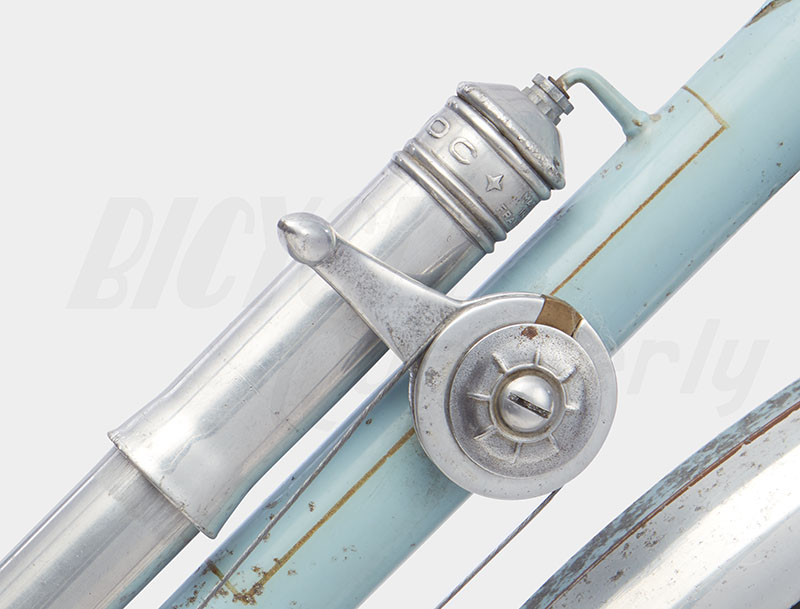

There were so many features that showed Herse’s attention to detail. The custom-made shift lever for the desmodromic Cyclo rear derailleur was eccentric, because the derailleur moves in and out, and without a return spring to take up the slack, the tension of the shifter cable changes. The out-of-center barrel of the shift lever compensates for that.

I was used to completely overhauling old bikes before I could ride them. The grease in cup-and-cone bearings dries out within a few years, especially if the bike isn’t ridden. Yet on the 1952 Herse, untouched for decades, the Maxi-Car hubs and the Rene Herse bottom bracket spun smoothly and didn’t require any maintenance. Only the headset needed cleaning and greasing. It didn’t take long to get the bike back on the road.

Except for sourcing tires. The Herse came to me with heavy utility tires, and 650B wheels were almost unknown in North America back then. Even in France, Michelin’s Axial Raid 32 mm tires were the best you could find. I had bought a set at Cycles Alex Singer during my trip to France.

Then came the much-anticipated first outing. I expected a ride similar to my touring bike – fun, but not the bike you’d take for a spirited ride – and yet this bike performed like my racing bike.

Just as much fun was the reaction of other cyclists. Back then, fenders and 32 mm tires meant ‘SLOW’ in capital letters. More than one rider remarked: “You’re going pretty fast on that old klunker!” Which of course was an invitation to accelerate and leave them behind.

Once we were able to source more suitable wide tires (Mitsuboshi Trimline 650B x 38s) with the help of Bob Freeman from Elliott Bay Bicycles/Davidson here in Seattle, there was no stopping the Herse. For one summer, I rode it more than any other bike.

Perhaps the bike’s greatest moment came a few years later. We had discovered the gravel roads of the Cascade Mountains, and Robin Piper was organizing the first brevet across Babyshoe Pass. The Three Volcanoes 300 was a wonderful course that started at the foot of Mount Rainier, climbed the slopes of Mount Adams, before completing its loop via Mount St. Helens. The first year, I rode my modern bike with 27 mm tires and struggled on the gravel of Babyshoe Pass.

In 2005, I hatched the plan to ride the old Herse. Shod with a fresh set of Mitsuboshi Trimlines, the bike absolutely flew on that course. Where I had been in the granny the year before, I now climbed most of the pass in the big ring. I’d never experienced riding on gravel like that.

It was a relentless charge over 11:49 hours, with just two brief stops to resupply. It was one of my most memorable rides, and, to this day, it remains the only sub-12 hour ride on this course. Riders stronger than me have tried, but on their racing bikes with narrow tires, they simply lost too much time on the gravel to Babyshoe Pass, even though more than 90% of the 190-mile course is paved. Modern all-road and gravel bikes, shod with more supple tires than those old Mitsuboshis, surely could beat my time. I’m tempted to give it another try!

That 2005 ride left us without a doubt: The 1952 René Herse was a blueprint for the bike of the future. A bike that combined the speed of a racing bike with the comfort and go-anywhere capabilities of wide tires.

It’s this bike that started the 650B resurgence in the U.S. It’s also this bike that showed us that wide tires could be as fast as narrow ones. Its geometry has inspired thousands of modern randonneur bikes, including my new bike for last year’s Paris-Brest-Paris (above). We’ve worked hard to create tires as supple and fast as the famous Barreau hand-made clinchers for which the 1952 bike was designed. I dreamed of bringing back the superb cranks and ultralight brakes of the old Herse. And in the process of all this research, I became friends with Lyli Herse… and that ultimately led to the rebirth of Rene Herse Cycles here in the Cascade Mountains.

Today’s best bikes, like the OPEN U.P.P.E.R. (above), can trace their inspiration to the marvelous mid-century Rene Herse, which demonstrated the long-forgotten fact that high performance and wide tires belong together. With wide tires no longer limited to ‘touring’ and ‘city’ bikes, a veritable ‘all-road bike revolution’ has swept the industry. And cycling is all the better for it!

Further Reading:

- The Spring 2020 Bicycle Quarterly goes deep into all the details of the 1952 René Herse with more studio photos and full specs.