Winning the Hellenic Mountain Race

When Meaghan Hackinen won the Hellenic Mountain Race a few months ago, we wanted to know more about this epic race and Meaghan’s experience. Here is her story:

The Hellenic Mountain Race (HMR) lived up to its reputation as a wild and unforgettable ride into the rugged Pindus Mountains of Greece. Unsupported, riders must travel 878 km (545 miles) on a combination of unpaved roads, tarmac, ancient stone paths, and singletrack, accumulating a staggering 27,800 m (91,200 feet) of elevation along the way. Riders have one week to make the finisher’s party in the Venetian port town of Nafpaktos and claim a spot in the general classification.

The first morning set the tone: after a short singletrack loop, riders bade farewell to Meteora’s dramatic monasteries and charged into the mountains on a 1,400-meter (4,600-foot) ascent. A confession: As much as I love the mountains, I have an aversion to steep drops, narrow trails, and rock gardens. Given the chunky terrain and sawtooth profile, I feared I was in over my head. My preparations were extensive and included adapting my setup (swapping drop bars for flat bars and adding front suspension to my bike), high-intensity training to increase my power on the double-digit pitches, and cultivating mindset strategies—namely patience—to match the terrain.

In the end, I had more fun than I expected, and genuinely relished the moment-to-moment adventure of moving through a challenging, but beautiful, landscape. As for standings, I took the women’s win and cracked the top ten with an official finish of 4 days, 7 hours. And I got one step closer to my big goal for the year: To become the first woman to complete all three ‘Mountain’ races: Atlas, Hellenic and Silk Road.

Getting There

My journey began in Athens a full week before the race kicked off. After a crowded Metro journey from the airport, I reassembled my Salsa Cutthroat and dragged its travel case across town to Vicious Cycles, where lead mechanic Jimmy Koutsovasilis offered to store it. A two-time HMR starter himself, Jimmy was returning for his third attempt, seeking a full brevet card and an arrival at the finish. (Spoiler alert: He succeeded—third time’s a charm).

After coffee with Jimmy, I rolled out of Athens in the afternoon heat—stoke level as high as my packs were full, loaded with everything I’d need to race, plus extra touring comforts: sleeping bag, full off-the-bike change of clothes, swimsuit and towel. (This is Greece, famous for its beaches.) I’ve toured to the start of other ultras like the NorthCape4000 and Transcontinental, and I find that the process settles my mind and body. Pre-race anxieties vaporize as the pedals turn. I enjoy sit-down meals, photo stops, and sunsets from the comfort of my bivvy.

Touring also offers an opportunity to get a feel for a place. In Greece, I learned that shops and restaurants are open late, but often close mid-day, that people are friendly (though English isn’t commonly spoken outside the cities), and that ice cream and gelato are abundant. I travelled with eyes wide open, taking in village squares, elaborate churches, and cats of every shade. Whenever I couldn’t make sense of the menu, I’d just ask for a recommendation—you can’t go wrong with Greek food.

I spent four days riding a 380-km (236 mile) route northward to Meteora on rural gravel and paved roads with very little traffic, including a short detour to the Thermopylae hot springs. One particularly hot afternoon, I was beckoned into the cool shade under an awning by a man sipping from a big green bottle of Alfa beer. I grabbed a non-alcoholic drink from a nearby convenience store and joined him for a conversation using our translator apps. The following evening, I checked into my hotel in Kalambaka (the town at the base of Meteora’s famous rocks), near the start. I was feeling good—ready for a few days of rest before ditching the touring kit to set out for the actual race on a lighter bicycle.

Not the Greece You’re Expecting

Even after touring to the start, I still held on to some of those twitchy pre-race nerves. Thankfully, it didn’t take long to find my groove. That’s the benefit of such an elevation-heavy course: It leaves little room for intrusive thoughts. I felt like I had no choice but to commit nearly all my energy to tackling the challenges at hand: pacing the climbs, safely navigating the descents, and keeping myself fed and hydrated along the way.

It didn’t take long before we entered the mountains. Pavement gave way to gravel, and I chattered my way up the first major ascent, where the landscape opened up to reveal green peaks traversed by lonely gravel roads. I grinned. This is what I was here for: the Greece you don’t see in tourist promos and friends’ vacation photos. Just then, I spotted the control car. Though not quite the milestone of an official checkpoint, the control car undisputedly signaled that I was on my way—and I took the opportunity to slam the door on any lingering insecurities and commit to racing my best race, regardless of outcome.

Forest Prison

In conversation with past HMR participants, I’d been forewarned about the most challenging features: singletrack right out of the gate, a dense and confusing stretch of trail known as Forest Prison, the many slippery-when-wet stone bridges and accompanying staircases, the hour-and-a-half bushwhack/hike-a-bike climbing out of a river gorge, the tough climb to CP3 via Karpenisi ski hill, and Diaselo Kaliakoudas—the unlikely pass that goes over rather than around the mountain. Plus a difficult pitch before the final descent to the sea. Knowing what I was in for helped me prepare mentally.

I reached Forest Prison sometime around midnight, after a downpour had turned the ground slippery. Between finding the trail and maneuvering around downed trees and other obstacles, riding was impossible for the most part. All day I had leapfrogged riders. Here, in the thick woods, we coalesced, our bike lights flinging beams in every direction as we searched for the track. Unlike some riders who cursed with frustration, I remained calm. And since like attracts like, I was joined in my bushwack by American rider Matt Schweiker, who proved exceptionally even-keeled during our nighttime foray. We eventually found the trail by identifying a discarded energy gel package—opting to leave it in situ rather than remove the trash, only because it would help others confirm they were on the correct path.

Time is slippery. Though I recall a series of ancient stone bridges, an out-and-back to Vikos Gorge (where I saw nothing but a sliver of bright moon suspended between clouds), and then picking my way through a rock meadow, I can’t remember where Matt and I split. Just like I can’t remember when I lost my sleeping mat. All I know is when I reached exhaustion at 3:00 a.m. and pulled over to rest under the cover of a church awning, I didn’t find it strapped to my seat post bag.

Creature Comforts

The second morning of the race began with a long paved descent to Konista Bridge, the first stone bridge I witnessed in daylight. The late-19th-century bridge was straight out of a fairytale, its weathered stones curving into an elegant arch over the Aoos River. Thunder from nearby waterfalls reverberated in my ears as I paused to snap a few photos and appreciate this engineering marvel. A river crossing also meant a low point, and I was content to linger a little longer in the stillness before embarking on what I correctly assumed would be an arduous climb back up the valley side.

Hours later, I reached Smolikas Refuge on the slopes of Mount Smolikas, Greece’s second-highest mountain, where thriving woodlands replaced the open farmlands of the morning. Heavy clouds released a steady drizzle. A steep hiking trail took me from the busy mountain refuge to the highest point on the route, at 2,080 m (6,824 feet), before plummeting down to the first checkpoint on what was described in the race manual as “epic mountain bike singletrack.” For the less technically proficient riders among us, that meant a 7 km (4.3 mile) hike down the mountain.

From Smolikas Refuge, I felt as though I was navigating in a cloud; I’m sure the views would have been spectacular in clear conditions, but I couldn’t see farther than the tread of my front Fleecer Ridge tire.

Even though I had pledged to walk all the difficult portions, I still managed to crash out when I attempted to bunnyhop some slippery blue piping. I arrived at the first checkpoint mud-spackled, with ruby red blood oozing from my right knee. After handing over my brevet card and ordering spaghetti bolognese, my attention turned to cleaning and disinfecting the scrape.

When I finally sat down to eat, my limbs melted into the worn wooden chair like parmesan on my pasta. The cosy atmosphere of Munti Smolikas Mountain Refuge was exactly what my body craved coming off the mountain. I spent several minutes idly pushing the last of my noodles around my plate, not wanting to leave.

The afternoon took me through Pindus National Park, an area renowned for its mountainous biodiversity, notably European black pine, Eurasian brown bears, and endemic flowers. In the rain, I sadly couldn’t see much of its unique features. With a deepening chill and both pairs of socks soaked, I found myself reminiscing about the comforting warmth of the checkpoint, and opted to stop early at 8:30 p.m. to get a few hours of quality sleep in one of Metsovo’s budget hotels.

Into the Wild

Day 3 proved to be my biggest—and best—day of the race, as the route soared high into the Pindus Range on less-travelled mountain roads. Despite the thousands of meters of climbing already in my legs, I welcomed the challenge. I was on the bike by 2:00 a.m. in clean, dry bibs after a luxurious three-and-a-half hours of sleep. As if to announce the route’s departure from civilization, I encountered a bear on the outskirts of town, which I initially mistook for a giant black dog. Thankfully, unlike the dogs in Greece, bears are afraid of people.

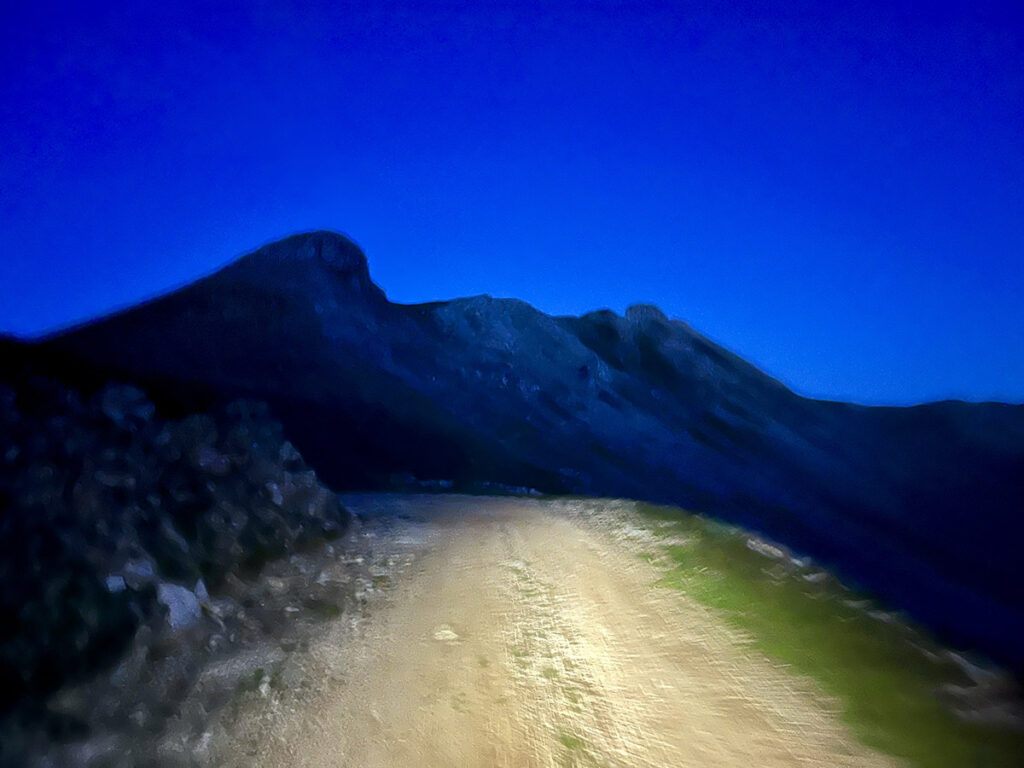

I huffed my way up the first climb of the day in absolute darkness. During longer events, I find RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion) a more useful metric than power or heart rate, so I’m afraid I don’t have any metrics to share—only that I regulated my output to match the climb. The night sky paled toward indigo as I reached the summit. I pulled out my iPhone for a quick photo before donning gloves and continuing onto a rocky high-altitude plateau. I could see for miles, and it seemed every twist in the rough gravel road brought an even better vantage point as color infused the landscape. But as much as I wanted to capture the moment, I could feel my body temperature plunging. I knew stopping to remove my gloves and dig my iPhone from my jersey pocket would be a mistake. Instead, my eyes welled up with cold tears of gratitude.

After a few wrong turns navigating the mountain village of Syrrako, a paved climb brought me to the second checkpoint in Melissourgi. Here I opted to change my used-up front brake pads while I waited for my chicken and rice. Some trouble pushing the pistons back into place meant that once again, I lingered longer than planned. But because I knew the next section, nicknamed ‘Little Kyrgyzstan,’ would be remote, I was okay with trading time to ensure my safety.

There was more climbing and another hike-a-bike. I rode past innumerable gushing streams that, in other circumstances, would have enticed me to strip down and cool off. The further I pushed into the mountains, the more I had to pinch myself—this felt like a dream. Only the jarring rock surface tethered me to reality, and when I flatted on a particularly rough descent, I wasn’t at all surprised.

Thankfully, the puncture proved easy to fix. I’m using Rene Herse Fleecer Ridge 29” x 2.2” tires with Endurance casing and filled with Rene Herse sealant. The puncture occurred between the tread knobs. Once I located the leak, I attacked it with my tire plug tool and a slim bacon strip. The hole—larger than I’d initially thought—ate the bacon strip, and so I tried again with a thicker strip. This one stuck. I pumped the tire back up and was off and rolling in less than five minutes. Happy to say that the fix held, and I haven’t experienced additional punctures since. Punctures are almost inevitable in a race like this, and I was glad the tire, sealant, and bacon strip all worked together exactly as they should to seal the puncture.

Tortoise Mode

It wasn’t until Day 4 that my legs began failing me. Until then, the challenges felt ridiculous, yet surmountable. But after a lousy 90-minute nap next to a dump truck, I woke up shivering, my legs cramping inside my emergency SOL biv, and my back sore from the hard ground. I missed my sleeping mat and wished I’d packed a sleeping bag.

Things didn’t improve much from there. My pace dwindled. Yet aside from stopping to snap a photo of a tortoise that crossed my path—a fitting metaphor, I thought—my competitive drive kept me in motion: Now that I had a sizable lead in the women’s field, I set my sights on a top-ten position in the overall classification. Dawdling wouldn’t get me there.

So, I practiced patience, checking off challenges as they came and reveling in the sense of accomplishment after each. My food stocks were depleted, but in a stroke of luck, I discovered a Mars candy bar on the trail. Perhaps if I’d been speeding along, I would have missed it and bonked on the climb up Karpenisi ski hill. Maybe going slow proved a blessing after all?

To the Sea

I didn’t expect the final miles to be easy—and, of course, they weren’t. In addition to the compounding impact of sleep deprivation, muscle fatigue, and heat, the stretch between Checkpoint 3 and the finish also contains the highest climbing ratio, gaining 6,300 m (20,679 feet) in just 190 km (118 miles). Plus, there’s no guarantee of resupply.

After a massive night climb over the fabled Diaselo Kaliakoudas, I holed up in a shelter for some overdue rest before making my final push. The hours that followed were stop-and-go: I napped, changed my rear brake pads, and cooled down in fountains as temperatures heated up. I was grateful—astonished, really—that my legs kept turning the pedals, carrying me through mountains upon mountains, albeit slower than I would have liked.

When I was on the absolute final climb and swore I could taste the sea, a massive electrical storm blew in. With the summit in sight, I sheltered under an overhanging shrub, waiting for the hail to pass. My rain jacket had gone missing, so I layered up as best I could, glad that I’d packed waterproof gloves. I struck out again once I thought the worst had passed, but miscalculated—the hail intensified as I made my break for the summit, turning to sheets of rain as I passed between the giant wind turbines that marked the top of the pass. But through lashing rain, I finally glimpsed the faint blue waters of the Corinthian Gulf.

The last 16 km (10 miles) into Nafpaktos were harrowing. I was riding on a surface that was more river than road, with deeply etched channels and red-brown mud. With no rain jacket and nowhere to shelter, I didn’t have much choice except to continue. Thankfully, the rain slowed to a drizzle by the time I reached the city. And after a few minutes of navigating traffic on busy one-way streets, I reached the finish. Behind the cheering crowd was the sea. I had arrived!

Now Meaghan is in Kyrgyzstan, where the Silk Road Mountain Race will start in a few days, on August 15. As she starts the third and last of the ‘Mountain Races’ of 2025, we wish her the best of luck—and a lot of fun!