Our Handlebars are not UCI-compliant—and we don’t care!

Just a few weeks ago, we suggested that the UCI might limit tire widths for road bikes in the future. Apparently, we weren’t too far off: Now the UCI has announced new rules regulating the width of … handlebars. A closer look at the rules suggests that UCI officials may be guided more by nostalgia than by a deep understanding of how handlebars work and how they’ve evolved in response to overall bike design and riding conditions.

For a while, Rene Herse was the only company championing narrow handlebars. In recent years, mainstream handlebars have become narrower as riders are seeking aero advantages. Reducing the rider’s frontal area is the most effective way to improve the aerodynamics of bike-and-rider. Bicycle Quarterly’s wind tunnel tests showed that lowering the bars by just 2 cm reduced wind resistance by 5%—more than a set of aero wheels. Our on-the-road experience suggests that 2 cm narrower bars have a similar effect. From that perspective, narrow bars are free speed. (They also can be more comfortable—see below.)

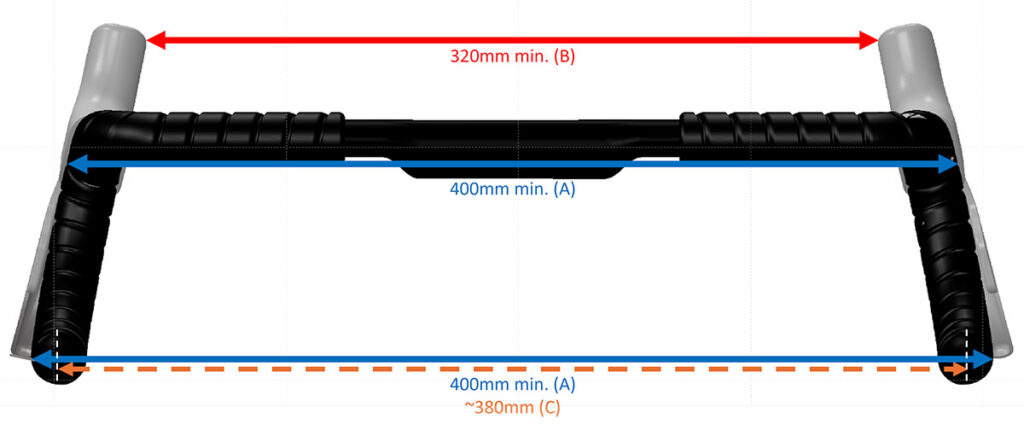

The new UCI rule specifies a minimum handlebar width of 40 cm, measured outside-outside, or about 38 cm center-center. Obviously, you could create brake levers that angle inward to get around the new rule, so the UCI has pre-empted that: The tops of the brake levers must be at least 32 cm apart.

The new rules also limit how much the handlebars may flare. The 50 mm measurement is taken from the inside to the outside. The UCI graphic suggests that this measurement includes the handlebar tape. That makes sense—you wouldn’t want to ask a rider to strip the handlebar tape on the start line when checking their bars.

Here is how this translates into more standard on-center measurements: The handlebar diameter itself is 24 mm, and the bar tape adds at least 5 mm on each side, for a total of 34 mm. That leaves just 16 mm of potential flare (less if the bar tape is thicker).

The new rules apply to road and cyclocross bikes. Track bikes have their own, somewhat narrower, limits. Nowhere do the rules mention gravel bikes. Despite the UCI’s attempts to exert their authority over gravel racing, they seem to have forgotten about gravel in this context.

Why the new rules? Cycling Weekly reported: “The UCI has said the change is due to safety after a trend for pros to adopt smaller handlebars in recent years, partly in pursuit of aerodynamic gains, had led to concerns smaller bars may compromising bike handling.”

Well, the 40 cm Rene Herse bars I run on most of my bikes measure just 36 cm at the ramps (center-center), so they are a full 2 cm too narrow. Mark VdK has the same bars on his new Rene Herse. And Natsuko rides 37 cm bars that measure just 30.5 cm at the ramps. And then there’s the issue of the flare. Rene Herse bars don’t flare a huge amount, but even at 20 mm per side, that’s more than the UCI rules allow—unless we run our bars without tape.

What about the UCI’s justification—rider safety? Both Mark and I have been riding our non-compliant 40 cm handlebars in a variety of conditions. Whether on the rough gravel of Unbound XL (above) or touring with fully-loaded front panniers (below), we’ve never felt any lack of stability or other concerns.

Of course, our wide tires add stability to the handling. Optimized geometries require only a light touch to guide our bikes exactly where we want to go. There’s no need to apply brute force to the bars, no need to force the bike to do things it doesn’t want to do. Steering these bikes is about finesse, not leverage.

It’s possible that some current race bikes are not yet optimized for wide tires and narrow bars, but that would resolve itself once manufacturers gain more experience with these developments.

Why do we ride narrow bars? One reason is aerodynamics—reducing the rider’s frontal area is the best and easiest way to improve the aerodynamics of bike and rider. Another is comfort. Your elbows articulate inward, not outward. Riders who bend their elbows to absorb shocks are more comfortable on narrow handlebars. (If you ride with locked elbows, your forearms angle outward, and wider bars may be more comfortable.)

I also ride 40 cm bars (with 36 cm ramps) in cyclocross—not for aero benefits, but because narrow bars make it easier to dive through narrow gaps when passing other riders on the narrow courses. With several fields on the course at the same time, getting through ‘traffic’ without delay is useful. Not once did I wish for wider bars when racing ‘cross.

Mark and I are a moderately tall riders, and we could ride UCI-compliant bars. But, as many have pointed out, this rule applies to riders of all sizes, including women. Natsuko runs 37 cm bars that measure 30.5 cm at the ramps (above). Her brake hoods are just 27.3 cm apart. That means Natsuko’s bars are not even close to UCI-compliant!

Could Natsuko ride wider bars? She once inadvertently tried… Natsuko spec’d the same 37 cm bars on her new bike, but Nitto had stopped making them. The builder substituted 39 cm bars, but forgot to tell her about the change. On the new bike, she felt uncomfortable, without knowing why. It took a while to discover that the bars were 2 cm wider than what she liked.

To make a long story short, with no narrow bars available back then, we added a 37 cm version of our Randonneur bars to the Rene Herse program. That was a few years ago—today, she’d be able to get narrow bars from a variety of makers.

Anybody who’s ridden with Natsuko knows she has no trouble controlling her bike, whether it’s on twisty paved descents or on the rutted trail across Naches Pass (above). To suggest that her bars should be 25% (!) wider for safety—is laughable.

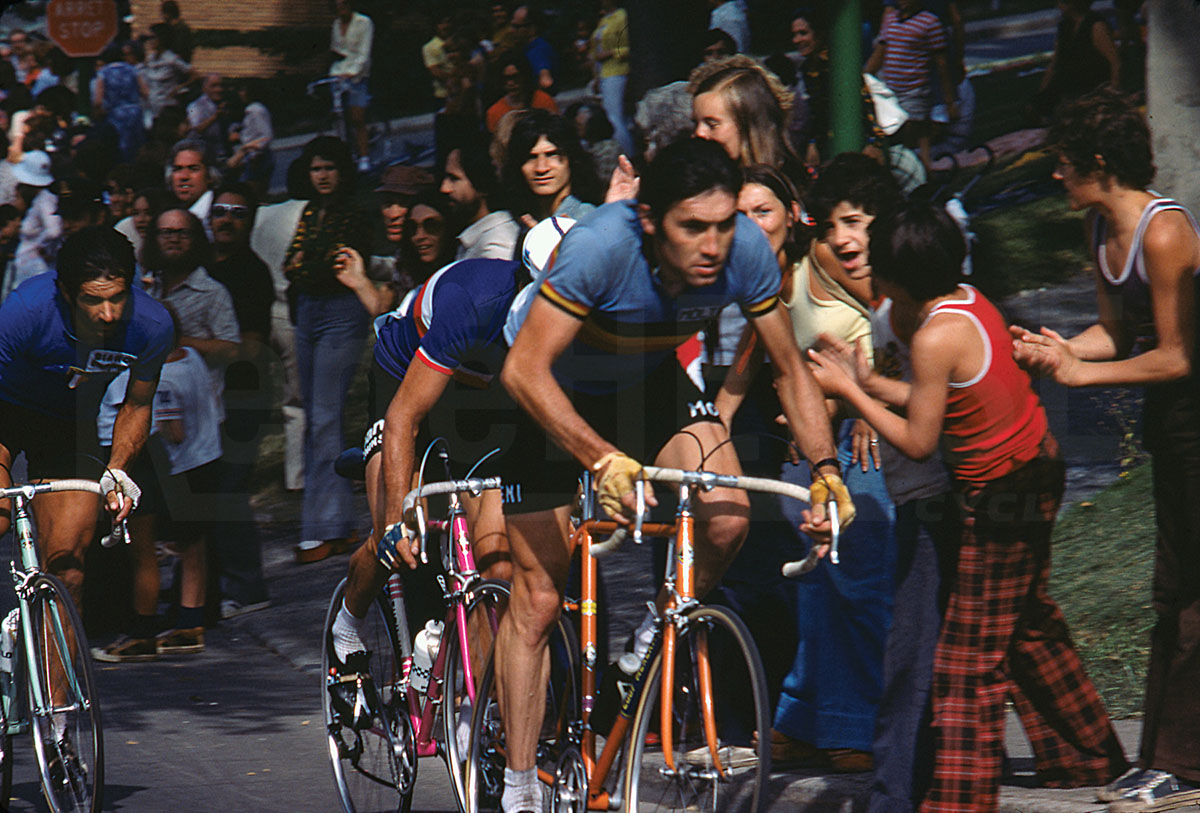

If narrow handlebars aren’t a safety risk, then what is guiding the new UCI rule? It may be nostalgia. Like so many people, UCI officials apparently want bikes remain the way they were when the UCI officials were young. During the 1970s and 1980s, handlebars were straight-sided and about 42 cm wide. Above is Eddy Merckx on the way to winning the 1974 world championships in Montreal in a photo from our book The Competition Bicycle. His bars are 42.5 cm wide (center-center).

If the UCI had looked further back in time and examined some earlier bikes, they might have realized that handlebars used to be narrower. In the late 1940s, Gino Bartali won the Tour de France with 39 cm bars—barely legal under the current rules. Even the tall Fausto Coppi was on 40 cm bars. (We measured the bikes of the champions when we photographed them for our book The Competition Bicycle. The book is long out-of-print.)

Handlebars got wider in the 1970s and 80s. Why? I suspect this was a response to the narrow tires of the time. Narrow tires have less pneumatic trail—they don’t stabilize the bike as much as wider tires. I suspect that’s why riders moved to wider bars, which helped control 1970s bikes with narrow tires and tiny contact patches.

Going back even further, during the ‘heroic age,’ when stages were long and roads were rough, many riders used bars with significant flare. I doubt the bars of Nicolas Frantz, winner of the 1928 Tour de France, would be UCI legal (above). If you look carefully, you’ll also notice that the Frantz’ bars have an upsweep like modern Randonneur bars. Long-distance comfort was important back then: The stage in the Pyrenees that included the Aubisque, where this photo was taken, ran over 387 km (240 miles). The fastest riders took over 16 hours to complete this monster stage.

In fact, Frantz’ bars look similar to modern gravel bars: narrow on top for comfort and aerodynamics, but wide at the bottom for extra leverage and stability on descents and rough terrain. It used to be that the drops were used to go faster—they offered a lower position. With today’s setups, riding on the hoods is just as low and more aero. On the hoods, the arms are angled forward, not downward—reducing the frontal area—and also narrower, due to the flare of modern bars. Today, the drops mostly serve for better control on descents, rough terrain, or in sprints.

Of course, narrow handlebars are not ideal for every rider, every bike, and every terrain. Wide handlebars have their place, and some riders and bikes are better with them. Here are the main advantages of wide handlebars:

- More leverage is good on high-trail bikes: Wide handlebars are almost a requirement on bikes with high-trail geometries, because there is more wheel flop. Bikes like that work well in tight, technical terrain, because the wheel flop of the high trail geometry—and the leverage of the wide bars—make it easy to turn the bars instantly. By contrast, road and gravel bikes need to be set up for corners and work best on flowing roads and trails. That’s why mountain bikes have geometries with a lot of wheel flop and wide handlebars.

- More comfortable for riders who lock their elbows: Our upper arms connect to our shoulders at an angle, and if you lock your elbows, your entire arms splay outward slightly. If your handlebars are too narrow, your shoulders feel strained when riding in this position. Bars that are wider than your shoulders feel more natural if you ride with your elbows locked.

And there’s also an element of rider preference—some riders like wider bars no matter the geometry of their bikes. For all those reasons, Rene Herse also offers all handlebar models in widths up to 500 mm.

For a while, it seemed that handlebars were getting wider and wider, and then the trend reversed. Why have narrow bars become popular only in recent years? The benefits of a smaller frontal area have been known for decades. During the 1990s, Greg LeMond developed the Scott Drop-In handlebars. They looked like normal drop bars, except they continued where normal bars end: They curved inward to allow an ultra-narrow position. (They weren’t successful, and even LeMond rarely used those extensions.) Just using narrower bars apparently was not considered, perhaps due to the narrow tires LeMond was running, which required more leverage to keep the bike from veering off course. (Or perhaps such a simple solution wasn’t sufficiently ‘high-tech’?)

Is it a coincidence that the trend to narrow handlebars coincides with tires getting wider, making bikes more stable, so that riders no longer need a lot of leverage over the steering to keep the bike going straight? It seems likely. Pro cyclists always try new things, but quickly abandon them if they don’t feel right. Seven years ago, pro racer Jan-Willem van Ship made the news for using 38 cm-wide handlebars—back then the narrowest in the entire peloton. As Natsuko found out, no maker offered bars that narrow back then, so Jan-Willem van Ship used old bars that he had taken off a touring bike! (When we introduced our 37 cm bars, I was tempted to send van Ship a set, since Rene Herse bars are stronger and much lighter than those old touring bars.) Back then, nobody else followed van Ship’s lead—perhaps because the bikes still ran relatively narrow tires and weren’t ready yet for such narrow bars. Then tires became wider, and suddenly narrow bars are everywhere. (Perhaps we should consider this an indirect speed benefit of wide tires?)

A few days ago, the UCI clarified their new handlebar rules and also the reasoning behind them: “These changes are part of an overall approach aimed at ensuring ever safer and fairer competition conditions, in a context marked by rapid technological advances and a significant increase in racing speeds that could have an impact on rider safety.” In other words, the UCI no longer claims that the narrow handlebars are unsafe by themselves, but that they increase speeds to levels that are unsafe.

If you want to slow down the racers, requiring wider handlebars makes some sense. Bar width easy to regulate—compared to, say, handlebar height, which would just lead to longer frames, allowing riders maintain the same stretched-out position. And the UCI is obviously aware that the many ‘aero’ features on modern bikes—like teardrop-shaped stem spacers or wing-shaped handlebar profiles—offer marginal gains at best. Outlawing them won’t slow down the peloton.

Other rules announced at the same time also attempt to reduce racing speeds. Rims will be limited to a depth of 65 mm. That rule has real safety implications, as anybody knows who’s ridden deep rims in crosswinds. The UCI will also test limiting the maximum gear to a 54×11. We’ll see whether that slows down the racers, or whether they’ll just train to spin faster. There are new rules about helmets, apparently to prevent aero helmets that drape over the rider’s shoulders from being used in road races. And finally, ultra-wide forks and rear triangles will be outlawed. Considering the marginal gains involved, I suspect this last change is driven by aesthetic concerns. The UCI has a certain image of what a bike racer should look like—Eddy Merckx in 1974 comes to mind—and many rules appear designed to preserve that image.

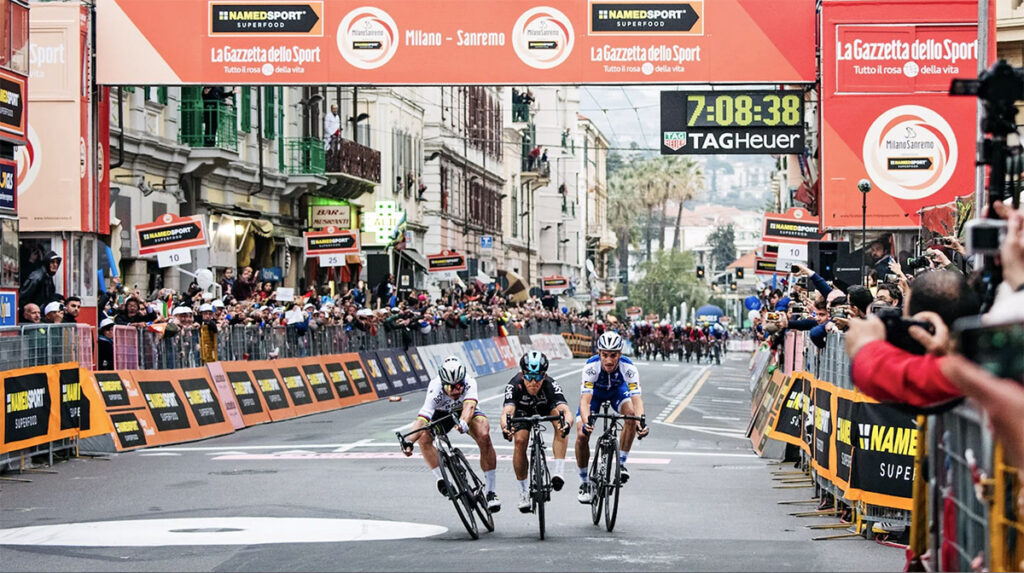

The discussions of the technical details tends to overlook the philosophical revolution that underlies the new rules: For the first time, the UCI wants to slow down professional racers to keep racing safe. We can argue whether racing has become less safe, but it’s hard to pin the blame on speed. Yes, speeds have increased, but not hugely so: The average in Milan-San Remo—a race that uses the same course every year—has gone up by about 7% since the early 2000s. To argue that going 7% faster suddenly makes cycling unsafe is a bit of a stretch.

It’s different in car racing, where the need to limit speeds has been an issue for almost a century. Speeds in excess of 250 mph (400 km/h) were already feasible in the 1930s. There have been many approaches to limit the speed of racecars: minimum weights, limits on engine capacity, restrictors that limit the airflow into the engines, even limits on fuel consumption. It will be interesting to see where the UCI takes this if they are serious about reducing racing speeds.

The UCI may argue that, just a few years ago, virtually all mainstream handlebars were legal under the new UCI rules, and few people complained that they couldn’t get ultra-narrow bars (except Natsuko). When we made narrow bars for Natsuko and other riders like her, we were renegades—the trend was toward wider bars. Many ‘experts’ were concerned that narrow handlebars would restrict riders’ breathing and impair their performance.

But that’s like saying that (almost) nobody was asking for wider tires on racing bikes a decade ago. There’s no reason to give up new developments if they provide real advantages. Now that riders have discovered the aero and comfort benefits of narrower handlebars, they are unwilling to give them up. Petitions to reconsider the UCI rule have been signed by thousands of riders, and many stakeholders have voiced their concerns. Let’s hope the UCI reconsiders their rule, especially for smaller riders like Natsuko.

Of course, UCI decisions don’t affect most of us. There is no reason for makers to stop offering, and for most riders to stop riding, narrow handlebars. Except that the mainstream bike industry tends to look toward racing for inspiration. Here at Rene Herse Cycles, we’ll happily ignore the new UCI rules. We’ll offer the handlebars that riders like Natsuko need, and that many others prefer. There may be a day again when we’re the only ones offering such narrow bars. That’s fine with us—we’ve never been afraid to swim against the current.

Further Reading:

- Natsuko’s story about how she discovered the 2 cm-too-wide bars on her new bike

- Why handlebar shapes are important for long-distance comfort

- Our book The All-Road Bike Revolution details how tires size, front-end geometry and handlebar width (and many other factors) interplay, and how to optimize them to obtain the best performance, handling and comfort.

- Handlebars in the Rene Herse program

Photo credits: Makoto Ayano (Unbound XL, 3rd photo); Jered Gruber (current pro racing photos); Ken Johnson (Merckx); Photosport International/Miroir Sprint Archives (Frantz); Jean-Pierre Pradères (Bartali bike); Marc Arjol Rodriguez (Unbound XL, all others); Westside Bicycle (Descending on Firefly)—all used with permission.