From Aircraft to Bicycles

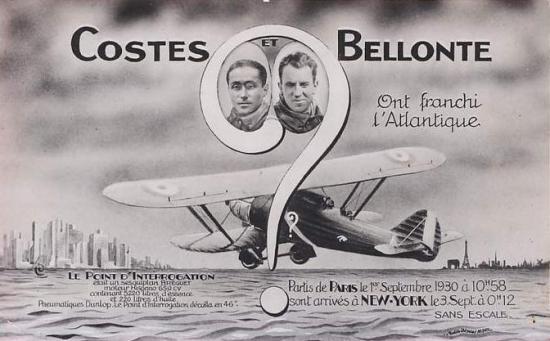

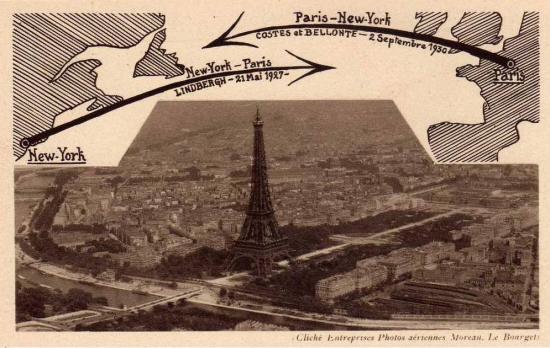

On September 1, 1930, two French pilots were the first to fly from Paris to New York. This was a huge achievement for them, but also their aircraft, since they flew against the prevailing winds.

Most people know about Charles Lindbergh, who had flown the other way just three years earlier. Lindbergh’s flight took great courage and a good portion of luck, and it was possible in part because he was aided by the strong westerly winds over the North Atlantic. Flying against the wind with 1920s aircraft technology was an entirely different matter.

Lindbergh’s Spirit of Saint Louis had a 223 horsepower engine and carried 425 gallons of fuel. The flight took Lindbergh 33.5 hours.

The plane that flew the other way, the Point d’Interrogation (Question Mark), was equipped with a 12-cylinder Hispano-Suiza engine, which put out a massive 650 horsepower. The plane carried 1368 gallons of fuel. Both the power output and the fuel capacity were roughly three times as great as on Lindbergh’s plane. Even with this powerful plane, the two pilots took over 37 hours to complete the flight, four hours longer than Lindbergh.

Building a plane that could carry this much heavy fuel was an engineering and manufacturing challenge, especially considering that 1920s engines were heavy and did not make that much power. The plane had to be light enough to take off and stay airborne for 37 hours, yet strong enough to withstand turbulences as it was buffeted by the strong winds over the North Atlantic.

The pilot, Dieudonné Costes (right), and his navigator, Maurice Bellonte, were veterans of many record attempts. They succeeded where 21 (!) attempts had failed over the previous three years. Five teams had perished trying to fly from Paris to New York.

Despite these difficulties and risk, Costes and Bellonte were not foolhardy daredevils. As Costes told the press before his flight: “The day we leave, nothing will be left to chance. I don’t want people to think that I am taking risks and being reckless. I have weighed everything, calculated everything. If we don’t succeed, then it is impossible.”

This careful approach extended to their Breguet XIX TF Super Bidon airplane. It was a very special plane, built in the prototype department of France’s foremost aircraft factory. The name ‘Super Bidon’ doesn’t need translation for cyclists: It refers to the fact that almost the entire fuselage was filled with fuel. The workers who built it called it Point d’Interrogation (Question Mark), because the ultimate purpose of the plane was secret even to them. The name stuck, and a question mark was painted on the side of the plane for the record attempt…

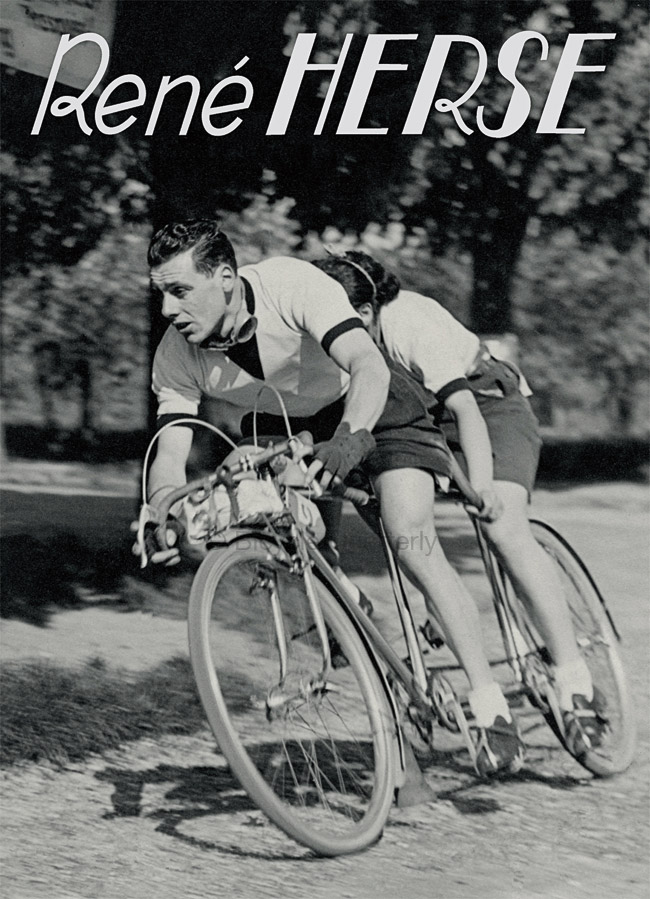

One of the workers who had built the Question Mark was René Herse (above, second from left). He learned his metalworking skills working on these prototype aircraft. At the time, engineering drawings often were quite rudimentary, and it was up to the fabricators to interpret them and turn them into metal. This is how Herse developed his magic feel for materials and stresses.

When Herse began making bicycles in 1938, he transferred his skills from prototype aircraft to bicycles. It is not surprising that his bikes were built like aircraft: They were light, yet strong. Reliability was his foremost concern – a plane over the North Atlantic cannot simply pull over to the side of the road if something goes wrong. And like airplanes, René Herse’s bikes were elegant because of their purposeful design, not because he added ornamentation.

To me, René Herse’s bikes have been an incredible inspiration. He was innovative, but he also had a great respect for solutions that had proven themselves. He came from a humble background, yet he made the bikes for a veritable “Who’s Who” of racers, randonneurs and high society. Even today, his bikes are hard to surpass.

My own bike (above) really is based on mid-century Rene Herse bikes—updated where technology has advanced. Its performance brings a smile to my face and enables me to push beyond what I used to think possible. Much of that is due to the genius of René Herse, which was formed in the years he worked on prototype aircraft.

Further reading:

- The René Herse story is told in René Herse: The Bikes • The Builder • The Riders