Lyli and the Puy de Dôme

We love history because the stories are so inspiring – real life is often better than fiction. One of my favorites is Lyli Herse’s record-setting ride up the Puy de Dôme in 1951.

Tour de France fans know the ‘Puy’ as one of the toughest climbs in France. Many times it has been decisive in the outcome of the Tour. Back in the 1940s and 50s, there was also an amateur hillclimb for randonneurs, the Grimpée du Puy de Dôme.

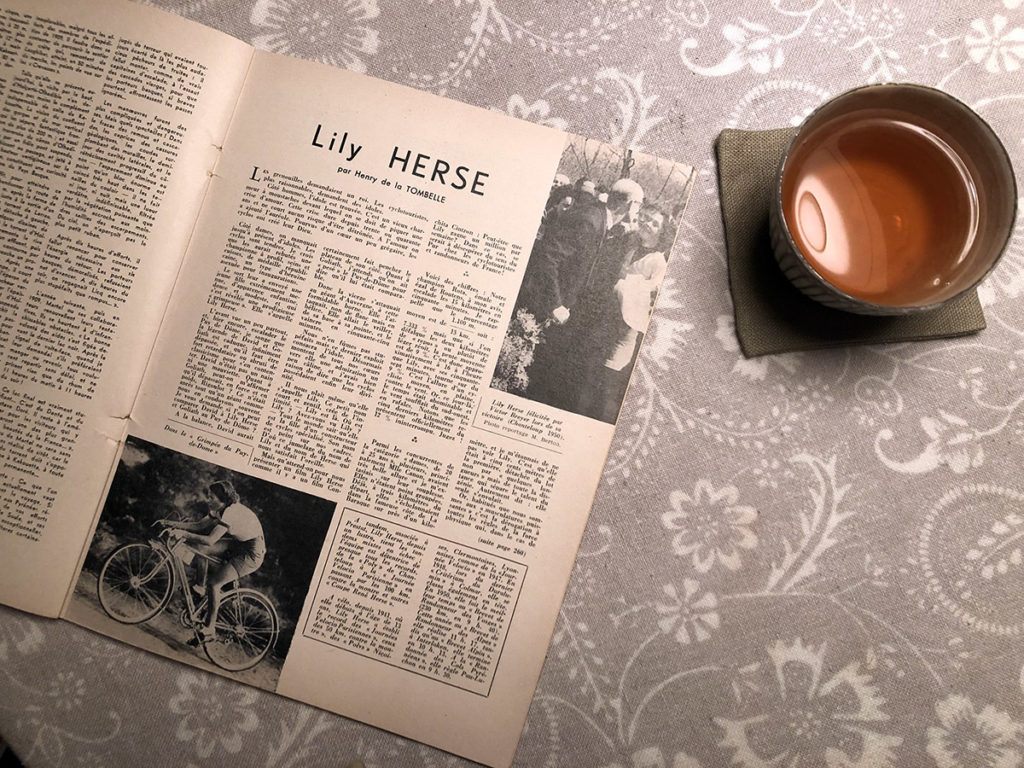

Lyli Herse’s specialty was climbing, and she showed that decisively in this event. She won the hillclimb race in 1949. She repeated this in 1951, when she set a record that remains unbroken today. The story goes that Jeannie Longo, the 13-times world champion who dominated several generations of female racing, tried to improve upon Lyli’s record, but without success. The poet and cyclotourist Henry de la Tombelle witnessed Lyli climb the Puy de Dôme on her record ride in 1951. He wrote:

“When one discounts the two kilometers of light grade that serve as ‘rest’ or, perhaps better, as a light reprieve, the average slope is 9%. That means that Lyli, with her time of 57 minutes, pedals approximately at 16 km/h [10 mph] on a slope of 9%. That is the speed of an average cyclist, on the flat, with a headwind. And that day, the weather was abominable, and the wind was blowing in gusts from the southwest. Remember that the last five kilometers officially constitute an uninterrupted slope of 12%. Think about that!

“Among the competitors in the category ‘Women, 20-25 years’ were several, especially Mademoiselle Canon, who rode very well, and I was impressed by their good form on the bike. They did not ride as a group. Just three kilometers from the start, they were already spread out over almost a kilometer on the famous Côte de la Baraque. I was surprised not to see Lyli. That’s because she was 500 m ahead, detached from the peloton not by ‘several lengths,’ but by the full distance that separates talent from genius. In other words: She had taken flight alone.

“Her pedal stroke, her silhouette were those of a born climber. Hardly arrived, after 57 minutes, she rolled up in a coat and watched the arrival of several competitors whom she had distanced with such ease.

“Describe her? But why? You all know her. It is the contrast which she represents that is so charming. Lyli at full speed, that is simply marvelous. It’s like Fausto Coppi before all his misfortunes. Once Lyli has crossed the line, the prize obtained, she becomes a little girl with a sad look, who does not make any noise, so quiet that one has to look for her, and does not always find her.”

So impressed was the poet by Lyli’s performance that he wrote an ode to her cycling performance (like most French, he misspelled her name as ‘Lily’). He eulogized that while cyclotouring already had a male hero – the late and immortal Vélocio – it had been lacking a female counterpart… until now. He wrote how, after her incredible ride, “Lyli disappeared into the crowd, and you had to go and find her. This wasn’t because she’s timid, but simply because her secret inner joy lies not in the victory, but in the effort itself.”

For more stories, check out our book René Herse: The Bikes • The Builder • The Riders