One Year Ago: Oregon Outback

Already a year has passed since I last rode the Oregon Outback, the 364-mile (585 km) bikepacking route that traverses the length of Oregon. That ride was the culmination of a dream that took seven years to achieve. Ever since the very first Oregon Outback—back in 2014 when it was a semi-organized ride and race—I had dreamed of traversing the rough trails and loose gravel roads of eastern Oregon at road-bike speed and with road-bike fun.

I rode that inaugural Oregon Outback on 42 mm tires. Those were considered huge back then, when gravel racers still were debating whether 32 mm tires were a good idea, or whether they should stick with their 28s. And yet my 42s bounced over the rough dirt and sank deep into the loose gravel, often slowing me to a crawl. Not only was this slow, it also wasn’t much fun.

The Outback made it crystal-clear to me that even wider tires would be faster, more comfortable and more fun. That started the trend to truly wide rubber… We introduced the Switchback Hill, Antelope Hill and Rat Trap Pass tires. Then I needed to build a bike around these new ultra-wide tires, without compromising the performance and versatility of the all-road bikes I usually ride in long events. And then I had to find the time to train and ride the event. It all finally came together last year. The first attempt, together with Lael Wilcox, was hampered by many mishaps. First I got off course, putting me out of contention for an FKT. Then I cut a tire sidewall—a first for me in 10,000s of miles of gravel riding. GPS troubles cost much time at night in the Ochoco Mountains. I don’t like making excuses, but I knew we could do better. Lael’s busy schedule didn’t allow a second attempt at the Outback, but I wanted to give it another try. Then came terrible wildfires that closed the course…

When the fires finally stopped burning, and the first autumn rains cleared the smoke, it was already late in the year. The equinox is not the best time for an FKT (Fastest Known Time) attempt, since it means riding almost as much at night as during the day. But the weather forecast looked good, and my schedule had opened up, so I hopped on the southbound train to Klamath Falls. It was now or never!

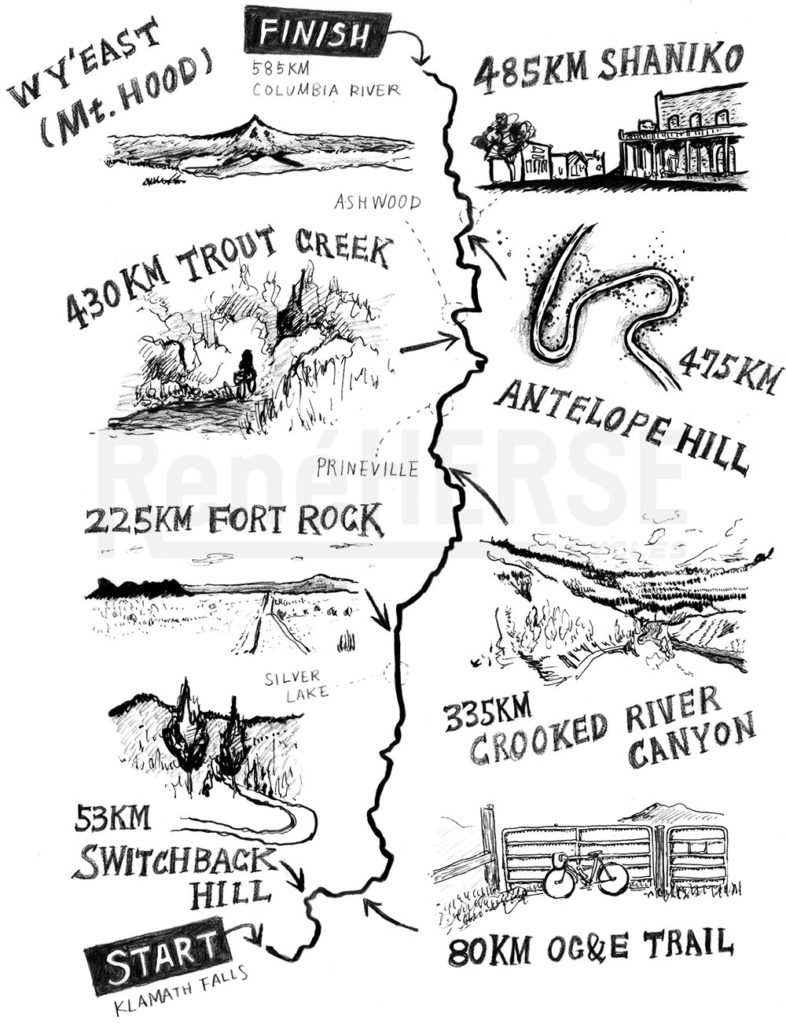

It’s rare that everything comes together perfectly for such a long ride, but when it does, it’s an amazing experience. My bike, my body, the weather, the terrain—everything worked in perfect harmony (or so it seemed). There was little time for photos, so Natsuko made the sweet map above for me, with highlights of the course.

Climbing Switchback Hill, the air was so clear that it was impossible to judge distances. What looked like small trees nearby turned out to be tall trees quite far away. The ochres and dark greens of the dry landscape contrasted with the cerulean blue of the sky. Eastern Oregon was achingly beautiful. FKT or not, I was just happy to be out there riding my bike!

The OC&E trail runs through cattle pastures, and there are dozens of gates that riders have to open and close. Cyclocross dismounts helped minimize the time loss, and then I was already in Silver Lake, the first resupply stop. I didn’t waste much time, and continued on the long stretches of soft gravel that make up the middle part of the course. Fort Rock passed, and my bike floated on top of the loose and soft gravel where it had sunk in 2014. The long straights that seemed interminable then now flew by at speed.

The sun set as I headed into the Crooked River Canyon. It was pitch dark for a couple of hours, adding excitement to the long descent on loose gravel. Then the moon rose. It was almost full, and it painted the cliffs of the canyon in a silvery light. I felt like I was riding through one of Ansel Adams’ famous night-time photos.

After the second—and last—resupply in Prineville, the Ochoco Mountains are the ‘moment of truth’ on any fast ride over the Oregon Outback. If you’ve overdone it during the first half of the route, the long climbs will slow you to a crawl. On this day, I had gauged my effort well. My legs were tired, but riding a great bike through the moonlit landscape gave me a boost of energy. I really enjoyed the twisty gravel descents. There was no traffic at all—I didn’t see a single car in the five or six hours it took me to get through the mountains. The famous crossings of Trout Creek were almost dry, so I rode them at speed. My bike bounced across the huge cobbles that make up the riverbed. I wasn’t sleepy before, but I certainly was wide-awake afterward!

Climbing Antelope Hill on smooth pavement, I turned off my headlight, so bright was the moon. My legs had little twinges of cramps—I’d forgotten to bring electrolyte tablets, and I’d been pushing the pace for 19 hours now—but I knew that they’d be fine. As I cycled through the fast-asleep town of Shaniko at the top of this last big climb, I checked my schedule for the first time. I realized that the FKT was possible. That knowledge, and a light tailwind, made the next hours pass quickly.

By the time the sun came up for the second time on this ride and illuminated Wy’East (Mount Hood) in the orange morning light, I was battling the many short, but steep climbs on the farm roads that run toward the Columbia River. The last climb, up Gordon Ridge, showed how close I had judged my effort. As the top came into sight, I wanted to accelerate, but my legs had nothing left. Then came the incredible 13-mile descent into the Columbia River Gorge. The wind whistled in my ears as the bike danced on the loose gravel. It was a fitting finale to a great ride.

Then I sprinted the last short mile on a flat road along the mighty Columbia River and turned into Dechutes River Park. My watch showed 8:43 a.m.—which means the ride had taken 26:13 hour. I had taken almost four hours off my 2014 time, and more than an hour off the FKT.

The finish was almost anticlimactic. It felt strange sitting on a bench, with no plan of how long to stay, or what to do next. For a day and a night, my entire focus had been on moving forward, as fast as possible. No need to think, just pedal, shift, brake, eat, drink. Tuning in to my body to gauge the effort, at the limit of what it could do, but never overdoing it. This single-minded focus was meditative in a way that I don’t experience otherwise, especially for such a long period of time.

Now the clock had stopped ticking. My mind was still full of the indelible impression of the ride. The beautiful landscapes. The incredibly blue sky. The moonlight. The way the bike floated across the bumpy trails, enticing me to pedal harder and smooth out the ride even more. The sights of Fort Rock and Wy’East, but also how the road wound through the hills just before Silver Lake, and how the water of the Crooked River rushed over the rocks—things you notice only on a bike.

Slowly I came back to the real world, where the future is as important as the present. In my case, the big question was how to get to Portland. The train station was more than 100 miles away, into a headwind that was increasing in strength by the minute. Just as I pondered whether to take a nap now or ride to the next town to get some food, a long-lost friend from my college days pulled up in his car. He’d followed my ride on the GPS tracker. Since he lives nearby, he came to see me. He was surprised to find me sitting all alone on a park bench—unsupported really meant just that. He offered me a ride to Portland. Catching up with an old friend was a nice end to this incredible adventure.

A few hours later, as I dozed off to sleep on the train to Seattle, I thought about my ride. It was hard, no doubt about it. But more than that, it was beautiful. It was fun, too. I compared it to my ride in 2014. My legs are no stronger than they were seven years ago. The roads aren’t any smoother. (In fact, the OC&E Trail is much more overgrown than it was back then.) And yet it had been easier, quite a bit faster and much more fun. For the sake of comparison, here are the known sub-30-hour rides on the Oregon Outback:

- 29:58 Jan Heine, 2014

- 28:08 Ira Ryan, 2014

- 27:58 Lael Wilcox, 2021

- 27:27 Steve Hartzel, 2020

- 26:13 Jan Heine, 2021

The other riders on this list are among the fastest racers anywhere. I wish I could claim stronger legs, but the difference is almost entirely due to the bike. (Back in 2014, Ira rode on 35 mm tires!) Riding on 54 mm tires was much faster, more comfortable and more fun on this challenging course than riding on 42s in 2014. Just as important, the new bike completed the 354 miles without any issues whatsoever: no flats, no bolts came loose, no cables needed adjusting. Apart from a squeaky chain caused by the dust and water crossings, the bike was as good as new after the long ride. (In fact, I rode it in this year’s Unbound XL without as much as an overhaul.)

As excited as I am about the FKT, I’m even more excited that the dream of a bike that can go on rough gravel and dirt at road-bike speed and with road-bike fun is no longer just a dream. These days, there are many great performance bikes with tires that would barely have fitted on mountain bikes in the days of the inaugural Oregon Outback. Back in 2014, the idea of 48 mm tires—or wider—on what is essentially a road bike seemed far out, yet it happened so fast! Perhaps all-road bikes with 26″ wheels will be next?

Further Reading:

- The Oregon Outback Rene Herse and the ride with Lael (above) were featured in Bicycle Quarterly 77. The full story of the FKT ride was in BQ 78. Both editions are part of the convenient ‘Past Year of BQ’ 4-pack.

Photos: Rugile Kaladyte (Photos 1 and 3; taken during the Spring 2021 ride), Mark Ahrens (Photo 2).