Paris-Brest-Paris – The Book

Paris-Brest-Paris is an event that captures the imagination. It’s not just the epic length of the ride – 1200 km or 750 miles – but also the history that makes this event special.

Paris-Brest-Paris (or PBP in short) was created in 1891 by Pierre Giffard, a colorful journalist, with two goals: Obviously, he wanted to increase the circulation of his newspaper, and what better way of doing that with reports from the most amazing bike racer ever? His second goal was more idealistic: Giffard wanted to showcase the utility of the bicycle at a time when it was mostly used as a fashionable pastime for rich young men, who paraded in parks and town squares.

Giffard saw the bike as a means of transportation, as a way to travel. His ideas for the race reflected this. He wrote:

“I dream of a truly utilitarian race, with racers who will ride the same machine from one end of the route to the other, and don’t change along the way, who will not try to devour the distance without taking an hour of sleep, who will sleep when their nature demands it, who will be true wandering cyclists, with bags and lanterns.” (Translated from French.)

Giffard dreamed of a randonneur event! Of course, this was long before randonneuring existed as a sport. As Giffard envisioned, the first PBP had numerous adventurous souls at the start. Among them were a handful of women, but they were not allowed to start.*

The limelight was stolen by two professional racers, whose newly-invented pneumatic tires gave them a huge advantage over the amateurs with their airless tires. In the end, Charles Terront, sponsored by Michelin, won over Jiel-Laval, who rode for Dunlop. Terront took only 71:27 hours for the long ride, whereas the last participants returned to Paris ten days after the start.

PBP was such a success that it was decided to hold the race every 10 years. The following events saw professional racers with full support, but also independents in the “Touriste-Routier” category. If you read French, you can read about the history of PBP, all the way up to this year’s ride, in Jacques Seray’s hardcover book Paris-Brest-Paris:12 ans, 1200 kilomètres.

For all readers, the main appeal of the book lies in the hundreds of photos. I thought I had seen most photos from the early days of PBP, but Seray found many more that I had never seen before.

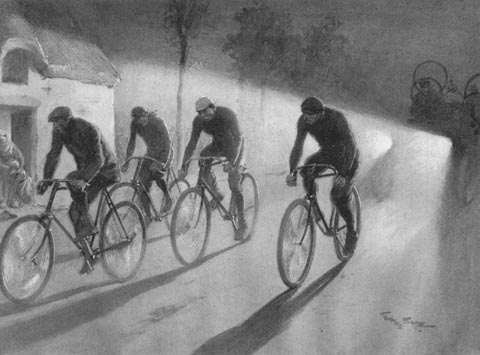

The photos include true gems. Above you see the decisive moment of the 1911 race: The leaders are getting ready to change their bikes as the race enters the hills toward the finish. You see their helpers running alongside with the spare bikes. However, the rider in the center, Emile Georget, attacks instead of changing his bike. He breaks away and wins the race.

Why did the racers change their bikes? Seray doesn’t mention the background, but from other sources, we know that racers back then did not use multiple gears. In fact, Henri Desgrange, the “Father of the Tour de France,” famously wrote: “Derailleurs are only for old men, who don’t have the force to face a hill head-on any longer.” (Desgrange’s main motive appears to have been commercial: The bike makers that financed the racing teams wanted to sell simple single-speed bicycles, rather than retool their factories for modern derailleur-equipped bicycles.)

The racers soon found that they could go faster if they adjusted their gearing to the terrain. The rules forbade them to use derailleurs, but they said nothing about changing bikes. So when a racer needed a different gear ratio, he simply changed bikes, with the new bike having different gearing. It may have been hypocritical for Desgrange to claim: “True men don’t change their gears!” when his true men in fact changed their entire bicycles…

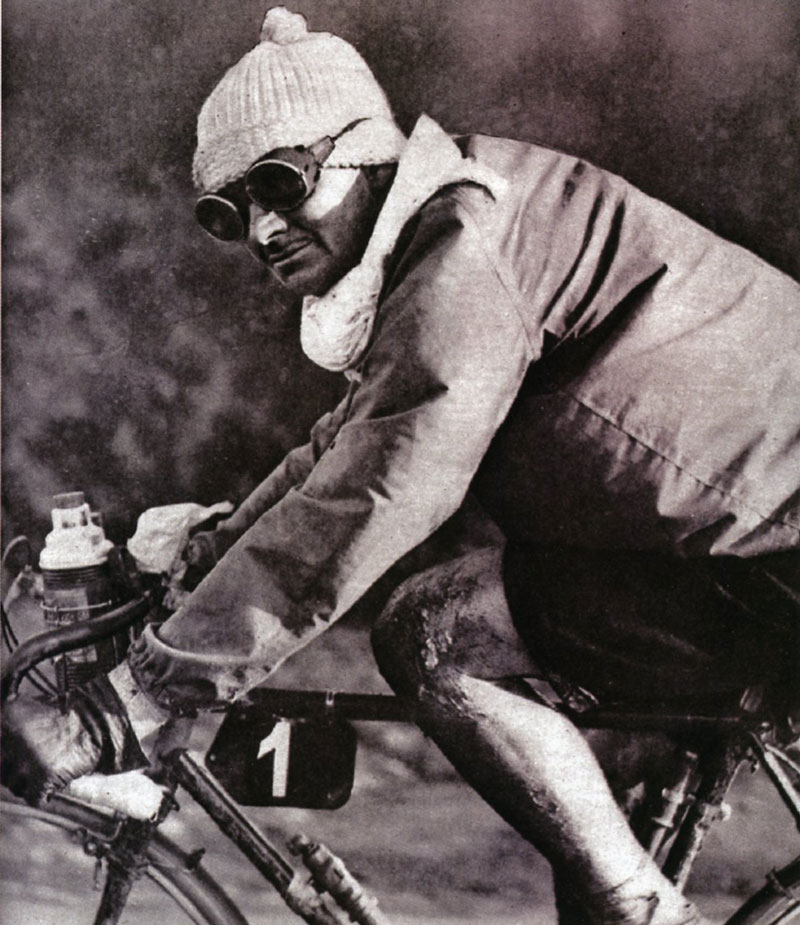

The race continued to hold the public’s attention every ten years. Most of the great riders associated with the famous event are shown in evocative photos in Seray’s book, including the Australian Hubert Opperman, who won the event in 1931 (above). Alas, there is no photo of Charly Miller, the only American ever to race in the professional PBP, unless he is one of the many unidentified racers shown in various photos. (It appears we don’t know what Miller looked like.)

In the 1950s, professional racers lost interest in the long race, but the randonneurs, who had been riding PBP since 1931, took over as the “Heroes of the Route Nationale.” Above is the start for the 1956 event, with Roger Baumann lined up in the center of the front row. He would be the first solo rider to return to Paris that year.

The randonneurs have grown in number in recent decades, and in 2011, almost 5000 riders took the start. Seray brings the story up to date with images and a report (in French) from this year’s PBP (above).

To make this wonderful book available to our readers, we are importing a few copies of Paris-Brest-Paris: 120 ans, 1200 kilomètres. Click here for more information.

* Women participated in unorganized randonneuring from the start. The randonneur PBP admitted women from the first edition in 1931.