Passing the Test

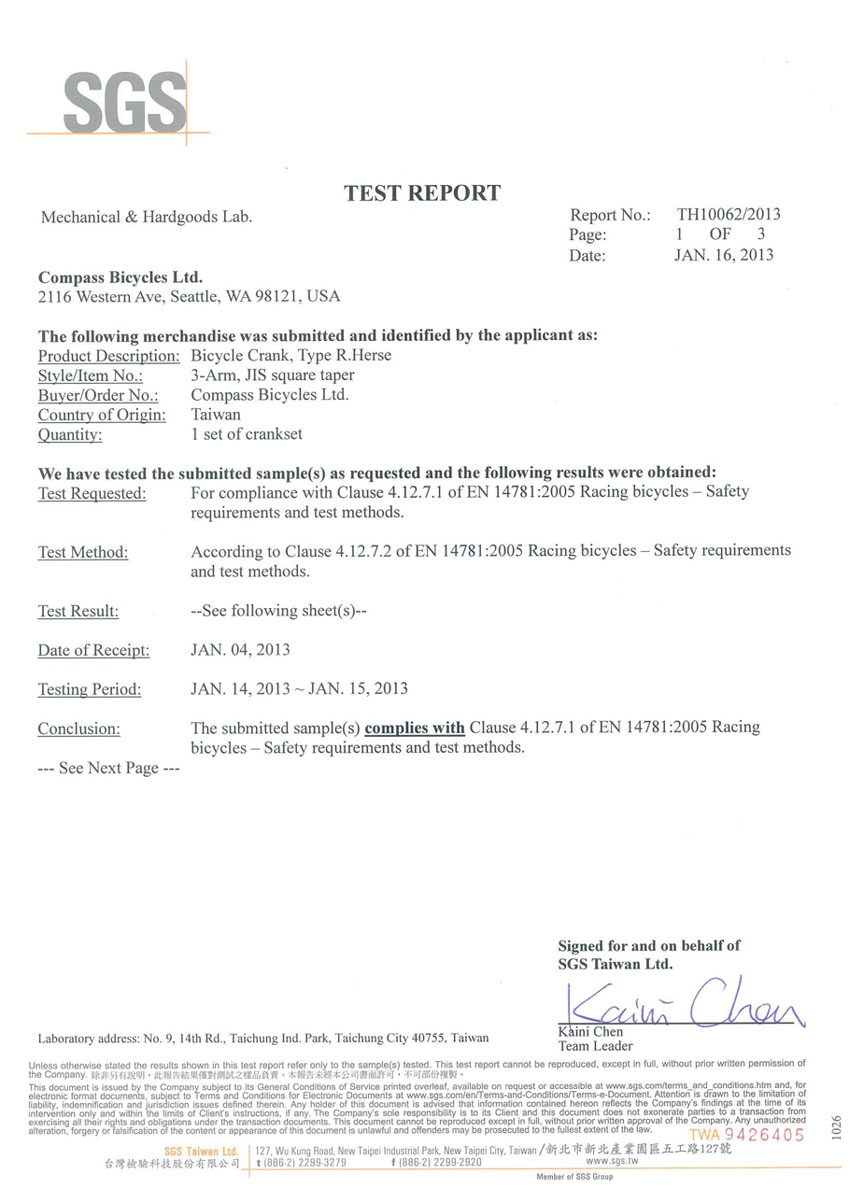

When we designed the new René Herse cranks, our goal was to create a crank that was as reliable and safe as any on the market. After all, we ride these cranks ourselves. We are especially proud that these cranks pass the stringent EN standards for racing bikes (EN 14781) with respect to fatigue resistance. We had our cranks tested by the Taiwanese subsidiary of the prestigious Swiss SGS testing lab. (Some other labs are reputed to be “easier,” but we wanted honest results, not a rubber stamping of our product.)

During the design process, we researched how other crank makers tested their cranks. We found that of the “boutique” and “classic” cranks on the market, none had passed the “Racing Bike” standard for fatigue resistance.

A number of makers (TA, Electra) had tested their cranks to the “City and Trekking Bike” standard. One company (White Industries) had done “some internal testing,” but didn’t recall the protocol. A budget maker of cyclotouring components did not provide any information. We later learned from an internal source that they had not tested their cranks at all.

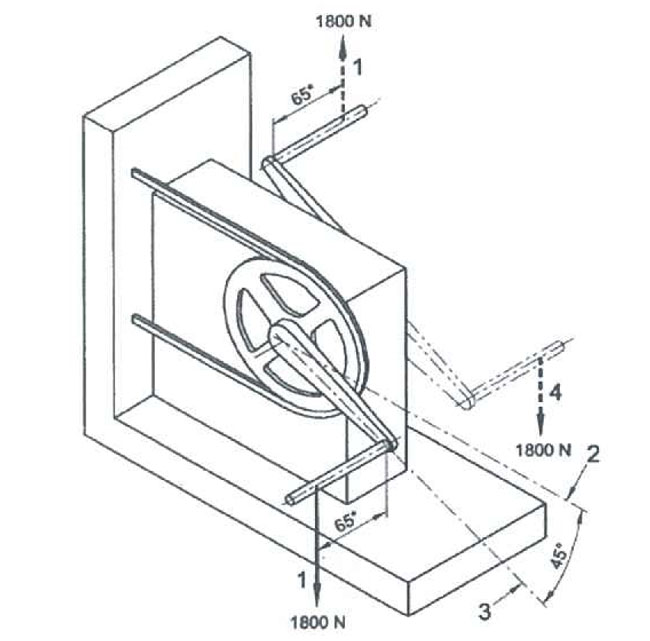

The “Racing Bike” standard is especially demanding because it loads the cranks with 1800 N during 100,000 cycles (above). By comparison, the “City and Trekking Bike” standard uses a load of only 1300 N.

I am lucky to know people in the bike industry from my days as a translator for several high-end bike companies. These engineers were very helpful when we designed our cranks, but they all doubted that a slender, classic crank could pass the “Racing Bike” standard. This demanding test is one of the reasons why cranks have become so bulky in recent years.

How does the René Herse crank manage to pass a test that other cranks fail, without adding the bulk that you see on many modern cranks? It’s a combination of factors:

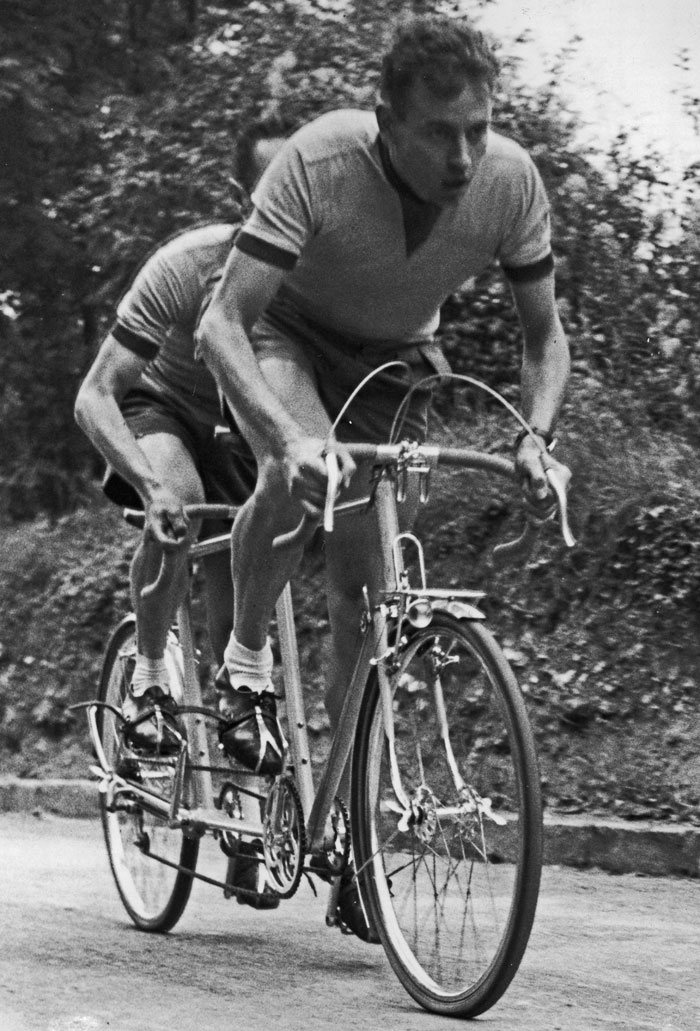

Proven design. The René Herse cranks have been around for more than 70 years (above during the mid-1950s), so we knew we had a sound design before we even did the first test.

The best materials and suppliers. We did not look for the least expensive forging company, but for the best one. We also selected the alloy of the arms for strength and corrosion resistance.

Net-shape forging. The raw forging already has the final shape of the crank, so the grain structure of the aluminum is not interrupted by machining. As a down side, this means that we can offer only a single crank length. We feel that the improved strength is more important than enabling customers to choose cranks that are 2% shorter or 2% longer than the 171 mm we offer.

A few other, proprietary manufacturing techniques maximize the strength of our cranks. None of these are rocket-science, but we were surprised that they are not commonly used during the production of bicycle cranks.

Of course, other cranks have been used without a rash of failures. Perhaps we are overly cautious, but I sleep better at night knowing that our cranks meet the most stringent standards. Crank breakages are rare, but they can have very unpleasant consequences.

Our cranks should last as long and be as safe as the best racing cranks you can buy, no matter how hard you ride. Because for all their beauty, René Herse’s bikes were intended to be ridden hard, as shown by Lucien Détée and Gilbert Bulté. In the photo below, they are on the way to setting a new tandem record at the Journée Vélocio hillclimb.