Renault or Bugatti?

To North Americans, it may seem odd that the most advanced classic bikes – the ones that have inspired our “real-world” randonneur bikes – came from France. When I was growing up, Italian bikes ruled. British bikes came second. A tier or two below these dream machines were French bikes.

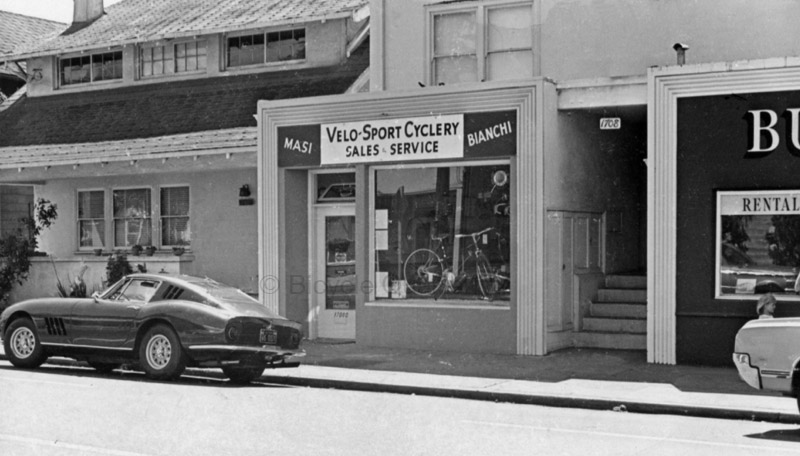

If you wanted the best, you chose an Italian bike: Cinelli, Masi, Colnago, Bianchi were names that cyclist revered. You bought a Peugeot, Gitane and Motobecane if your budget was limited: You got a bike with a full Reynolds 531 frame for half the price of a Cinelli. So you put up with some gaps in the brazing, accepted black-painted instead of chrome-plated lugs, and lived with components that lacked the finish and finesse of Italy’s best.

In the car world, it was similar: You dreamed of an Italian Ferrari or Maserati, or at least an Alfa Romeo. French cars rarely were at the top of the list: Renaults had a dodgy reputation for rust. Citroëns were stricken with poor reliability (caused mostly by mechanics unfamiliar with their advanced technology). Peugeots appealed only to people who weren’t really into cars. Yet today, many of the most prized cars, the ones that win awards at Concours d’Elegance and are featured in magazines, were made in France.

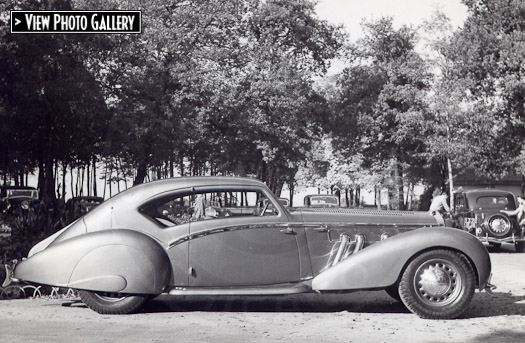

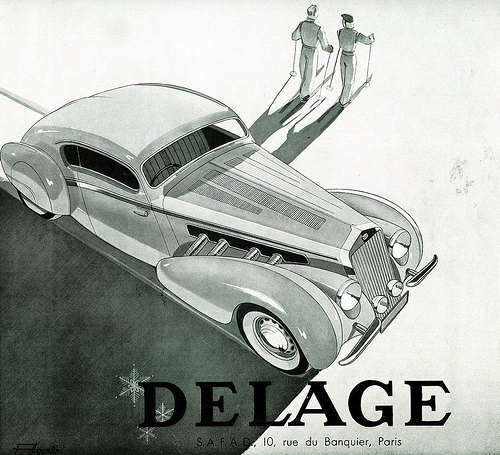

With French cars and bikes, you need to look further back to understand why they are now considered among the very best. During the 1930s, many of the world’s best and most glamorous cars came from France. Bugattis traced their “pur sang” (pure blood) directly to the race cars that dominated during the 1920s. Delages (above) were the ultimate in sporting luxury. And the swoopy Delahayes and Talbot-Lagos (top of the post) were show-stoppers unlike any others. And even the mass-produced machines from Citroën were innovative: They introduced unibody construction and front-wheel drive on a large scale.

It’s easy to overlook that France has long been a leader in technology. The French built Europe’s first space rockets, the first supersonic passenger plane (the Concorde, together with the British), and Europe’s first high-speed trains. Some of the famous car makers are still in business, too. Hispano-Suiza makes jet engines. The original Bugatti company is the world’s largest producer of landing gear for airplanes. Their high-tech expertise made it easy for them to get out of the unprofitable luxury car market and into more lucrative aerospace work.

Speaking of aircraft, during my research for the René Herse book, I learned that both Ettore Bugatti and René Herse worked at the Breguet aircraft factory during the 1920s (Bugatti) and 1930s (Herse). Perhaps this explains why the custom screws on Bugatti’s cars share some design elements with those on Herse’s bikes?

The cross-pollination between the makers of aircraft, cars and bicycles was not limited to René Herse. Louis Delage was a customer of Camille Daudon’s, and he later wrote that his Daudon was the most marvellous piece of machinery he’d ever owned. This from a man whose company made some of the first V12 engines!

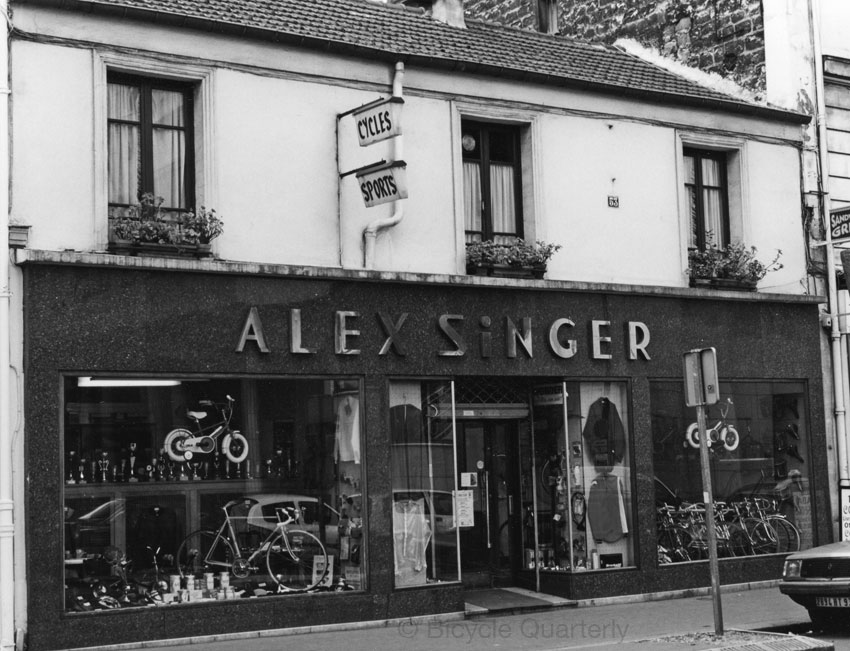

Key to understanding the French bicycle builders is their location. Herse, Alex Singer and Daudon all had their shops in or near Levallois-Perret, a suburb of Paris that specialized in high-end metalworking.

Levallois-Perret was an extraordinary place. The Citroën factory was just across the Seine. The factories of Hispano-Suiza and Delage were nearby. And when Ettore Bugatti designed aircraft engines during World War I, the government installed him here, too. The reason for this concentration was simple: There was a great network of machine shops, foundries, platers…

For the bicycle makers, this meant that they had incredible resources right at their doorsteps. Making stems, brakes, cranks and bottom brackets requires sub-contractors who can forge and machine the components required.

There also was a large pool of skilled labor. Jean Desbois, long-term framebuilder at René Herse, told me how he was hired by Herse when the machine shop where he worked closed during World War II. (His boss didn’t want to work for the Germans.) A number of similarly skilled workers found refuge with the constructeurs of bicycles. It appears that the Germans didn’t expect the bike makers to be of any use for armament production, so they just ignored them. Good thing they didn’t know that Herse was an expert machinist who had worked on prototype aircraft!

It’s much easier to make great bicycles when you are in a neighborhood full of people like Desbois, who was an expert metalworker. During the late 1940s, the lugs on Herse’s frames were filed by two workers from the Morane-Saulnier aircraft factory, who came by the Herse shop after hours. Desbois told me: “They were experts in filing metal.”

Not only did the constructeurs have all the resources needed to make highly advanced bicycles, but they also had a ready clientele. Engineers and other professionals appreciated fine bicycles, and the more technologically advanced the bikes were, the better. These customers not only appreciated every detail of the bikes, but they also were willing to pay for custom racks, lighting wires that ran inside the frames, and innovations like the carbon brushes inside the steerer tubes that transmitted the lighting current from frame to fork without external wires.

This confluence of factors did not exist in other countries, where cycling was very much a working-class sport. Neither Enzo Ferrari in Italy nor the Bentley Boys in Britain had any interest in bicycles. There was little market for ultra-high end cyclotouring bikes.

The great machines from builders like Herse, Singer, Daudon, Routens and Barra have little in common with the mass-produced French ten-speeds that became popular in North America during the Bike Boom. Just like the Bugattis and Delages of the 1930s came from a different world than the sad Renaults that were sold in the U.S. during the 1980s.

The glorious French cars of the streamline era are unaffordable and impractical today, but the bikes of René Herse and the other constructeurs remain as exciting to ride now as they were then. The cars may be distant dreams from a bygone era, but the bikes of René Herse and the other constructeurs have inspired a new generation of North American constructeurs. Their bikes are ridden every day, and they give their riders as much joy as the originals did more than half a century ago.

Further reading: René Herse: The Bikes • The Builder • The Riders

Photo credits: David Cooper, Cooper Technica (Delage Aerosport), Peter Rich (Velo-Sport with Ferrari)