Technical Trials – What is Innovation?

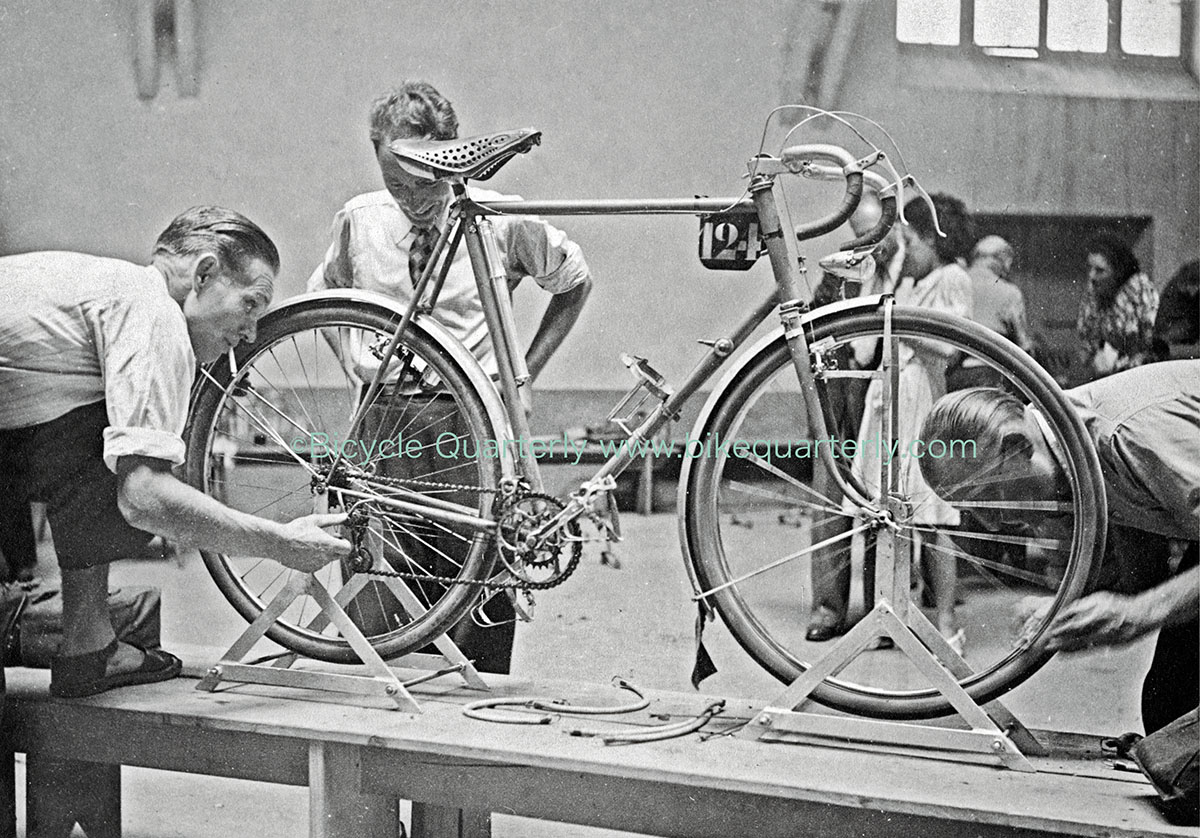

Next weekend, the Concours de Machines (Technical Trials) will be held in Ambert, France. The Concours is a competition between bikes, not riders, with the goal to find the best “light randonneur bike”. Bikes will be weighed, judged on their features, and then sent on a challenging course over three days to see how they hold up in real-world riding. It’s an exciting event with an illustrious history: Many of the things we now take for granted – aluminum cranks, front derailleurs, cartridge bearings in hubs and bottom brackets, even low-rider racks – first proved their worth in the original Concours de Machines of the 1930s and 1940s (above). The question for this year’s event is how much our current machines can still be improved. The organizers place special emphasis on innovation in the judging of the bikes.

Last year, I was a member of the jury. This year, my role is that of a participant, riding a J.P. Weigle – coincidentally the only American entry in an international field of 30 builders. The bike for the Concours is collaboration between Peter Weigle and Compass. Peter built the bike, and Compass worked on sourcing the components. Together, we spent quite some time thinking about the goals of the event: to find the best “light randonneur bike”, with a special focus on innovation.

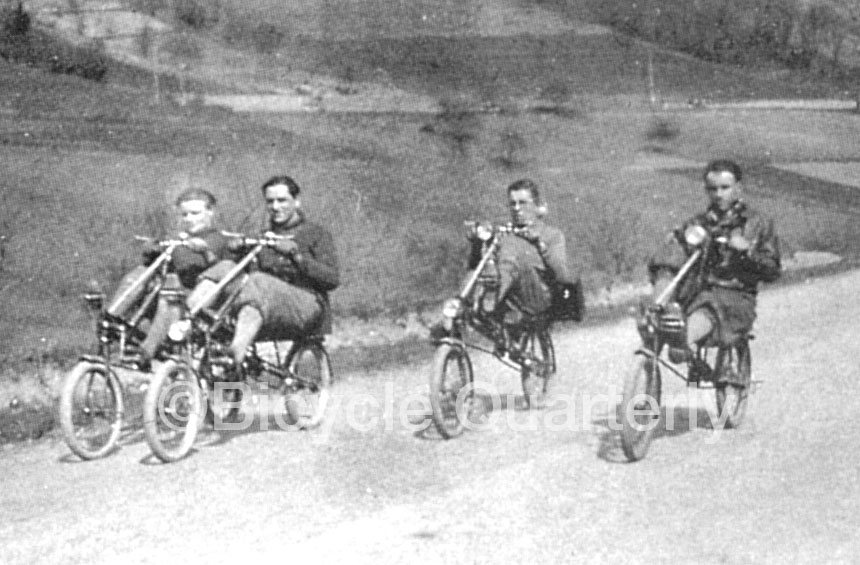

What is innovation? Is it a radical departure from the diamond-frame bicycles most of us ride today? Already in the 1930s, recumbents were popular for a while (above), but they’ve never made a break-through… because the classic diamond frame just works incredibly well.

Or is it a bike with special features that aren’t found in the mainstream? At last year’s Concours, there was a fully suspended bike, but neither the front nor the rear of the bike moved when I pushed on the handlebars and saddle. Perhaps it was for the better – the “rigid” bike performed quite well on the road – but to us, innovation that doesn’t work isn’t innovation.

For us, true innovation has to improve the riding experience or the performance of the bike. We examined every part to see whether it could be improved. We considered disc brakes, but decided against them because they a) are heavy and b) preclude the use of flexible fork blades that do so much to absorb road shock during long rides. We thought about carbon fenders until we found that aluminum ones are lighter. In the end, the bike that I’ll ride in the Concours looks remarkably similar to the bikes that Peter usually builds (above one of his recent machines). Perhaps that isn’t surprising, because these bikes are the result of decades of fine-tuning and evolution. So if “radical innovation” isn’t possible, what else could we do?

The second consideration of the Concours is light weight. Bikes have to weigh less than 10.5 kg (23.15 lb) to avoid heavy penalties. That sounds achievable until you realize that this weight includes bags to carry a load provided by the organizers, spare tubes, tools, etc. – the motto is “Nothing in the rider’s pockets.” And the bike has to be equipped with “autonomous” lighting (no batteries), fenders, a bell and even a pump. All this adds up, and suddenly you realize that unless you resort to crazy lightweight parts that will barely last through the weekend, it won’t be easy to avoid the penalties.

The course includes plenty of rough gravel roads, so wide tires are a necessity. Fixing flats will slow you down, and if you don’t make the required 22.5 km/h (14.0 mph) average speed over the mountainous 250 km/160 mile course, you will incur penalties, too. The idea is that the bike must offer good performance, and it should be ridden hard to show up any deficiencies.

So we went through every part of the bike, especially the Compass components: How could we lighten them without compromising reliability or performance. The gains were incremental, but they added up to a significant weight savings on parts that already are among the lightest available today.

One example is the ultralight rack Peter Weigle built (above). At 137 g, it’s incredibly light, and Peter cautions that it’s not designed for much more than the 3 kg (6.6 lb) load the bikes will carry during the Concours. And yet it is only 31 g lighter than our standard Compass rack that has withstood years of hard riding with heavy loads on rough roads. There were other parts where we felt that even for hard use, we could lose some weight. This means that the bike for the Concours will lead to better – or at least lighter – components that our customers will be able to buy in the future. But first the superlight parts have to prove their worth during the harsh test of the Concours and beyond, because Peter Weigle’s bike isn’t just intended for one weekend. It will be ridden, and ridden hard, for many miles.

Once all the participants meet in Ambert at the end of this week, I’ll report more on the details of our bike, as well as the machines of the other competitors. The goal of this event is pushing the development of real-world bicycles to new heights, and I already know that in the case of Compass, the goal has been achieved.

Photo credit: Peter Weigle (rack); Nicolas Joly (night photo)