Why Light Weight?

Recently, a reader asked: “Why are you so focused on saving a gram here or there? For the 99.999% of us who are not professionally racing, but just wanting to get out there and ride, shouldn’t the focus be on function and longevity?”

Of course, the reader is right – some of the bike industry’s ‘weight weenie mania’ is misplaced. I shake my head when we get a Bicycle Quarterly test bike with aluminum screws for the bottle cages that are already stripped from the initial installation, or when adjusting the saddle height is a major operation with tiny screws that you don’t want to attempt by the roadside. But statements like “Weight doesn’t matter!” are just as misleading.

We strongly feel that a bike shouldn’t be heavier than necessary. Why? What are the advantages of a light bike for ‘normal’ riders? If you read our book ‘The All-Road Bike Revolution,’ you’ll see that it’s not about arriving at the top of a long mountain climb a few seconds earlier – as important as that may be for racers – but about function, feel and elegance.

When you optimize a component, you fine-tune it through many iterations until you have just the right amount, of only the best materials, in just the right places. That means your component will inevitably be light.

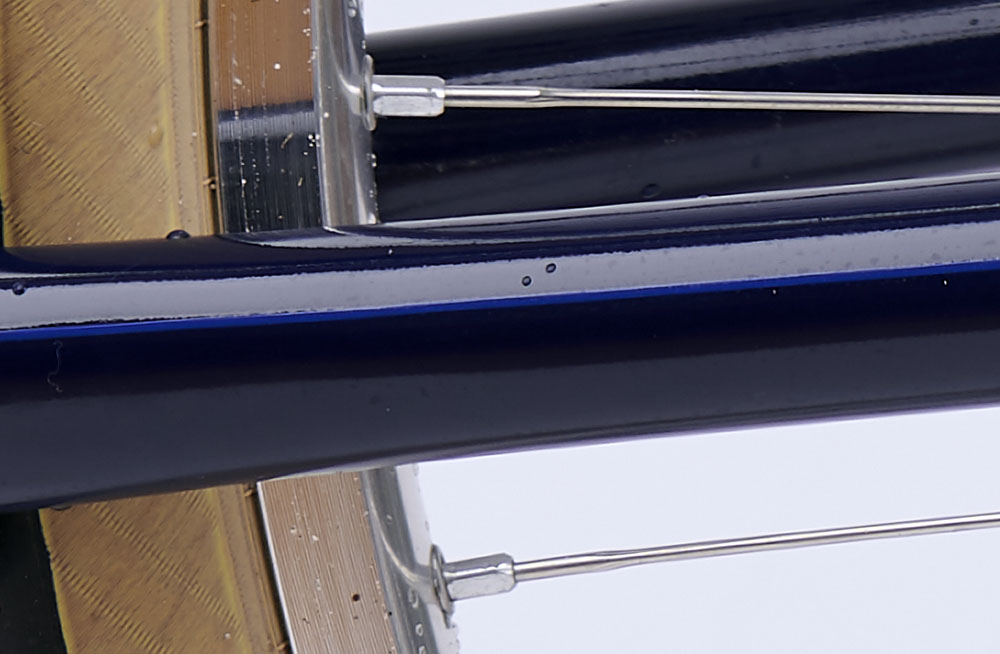

Take our centerpull brakes, for example. We used Finite Element Analysis to optimize the arms, to put material only where it’s needed. That actually makes the arms stronger, since they are loaded uniformly across their entire length, without stress concentrations. We mount the brakes directly to the fork blades and seatstays. Direct mount brakes save weight, but they are also more powerful, since they flex less. Less flex means that their modulation is better, too, since the angle of the brake pads doesn’t change as they squeeze the rim harder. Less weight, more power, better modulation – all these positives go hand-in-hand.

And since our brakes are already among the lightest in the world, why not make titanium versions of some bolts where this doesn’t affect function? (For riders who aren’t concerned about weight, we offer the brakes with steel bolts, too.)

The titanium bolts exist for a reason: A light bike feels different from a heavy one. And a light bike isn’t the result of one or two superlight parts, but of shaving 20, 50 or even 100 grams from every component. It all adds up – my blue Rene Herse weighs just 10.2 kg (22.5 lb) fully equipped; my Firefly (above) breaks the 10 kg barrier despite its huge 54 mm tires. Many similar bikes with heavier-than-necessary components weigh almost 50% more. That is a difference you can feel when you ride. When you climb out of the saddle, when you accelerate past a bus that is about to pull out of its stop, or when you lean the bike into a corner during a mountain descent, a light bike reacts differently from a heavy bike. And that is independent of how much the rider weighs.

It’s that lightweight feel that makes a 17-pound carbon all-road bike so much fun. For many riders, it’s worth putting up with parts that aren’t designed for more than a few years of hard riding. I can understand, but it’s not how we do things at Rene Herse Cycles. Our goal is to capture that lightweight feel without compromising function or longevity.

In fact, all our components could be lighter, if that was our only goal. Take our tires: We put a millimeter of extra rubber in the middle of the tread, so they last twice as long. (Since you can’t wear down the last millimeter, a 3 mm-thick tread has twice as much rubber to wear off than a 2 mm tread). It adds a few grams, but our tires aren’t ‘event’ tires that you put on for a special ride and then take off again. Our tests have shown that with a supple, wide tire, adding a little rubber in the middle of the tread doesn’t make it roll slower, so there’s really no reason to make ‘pre-worn’ tires – unless you are chasing every last gram.

Our brakes fall in the same category. They are among the lightest in the world, but we don’t use ultra-thin pads like almost everybody else today. Our pads are much thicker, so they last more than just one winter of riding in rainy Seattle.

Our cranks are so strong that they pass the EN ‘Racing Bike’ standard for fatigue resistance. That’s the toughest standard for road cranks – much more demanding than the more common ‘City/Trekking Bike’ test. The only way to pass the ‘Racing Bike’ test is to ‘net-shape forge’ your cranks. This means that you forge them with tooling that is exactly the same shape as the final crank. (Many less expensive cranks use ‘multi-crank’ tooling that makes a ‘crank-shaped object,’ which then is machined down to the final shape of the crank.)

Net-shape forging makes our cranks so strong that there’s no need for heavy bulk. Our cranks among among the lightest in the world, yet they will last through many more fatigue cycles than cranks that are heavier and less strong.

Spokes are probably the best example of how optimized components are lighter and stronger. Double-butted spokes are thinner in the middle than at the ends, so they are lighter and more aerodynamic. They are also stronger. Spokes fatigue when they get de-tensioned as the wheel compresses at the bottom. Each time the wheel turns, each spoke goes through one cycle of de-tensioning and re-tensioning. After many, many cycles, the spoke will break. Thinner spokes stretch more at the same spoke tension, so they lose less tension as the wheel compresses. This means that thinner spokes fatigue much less.

If spokes fail, they break at the ends, and that’s where double-butted spokes have the same amount of material as thick straight-gauge spokes. That makes double-butted spokes a ‘win-win’ idea: The ends are as thick and strong as straight spokes, while the middle is thin to reduce fatigue. And on the Sapim spokes we sell, the ends are as short as possible, which maximizes the advantage (and minimizes the weight). The only down side of butted spokes is that they wind up more as you tension the wheel, so they require more skill from the wheelbuilder.

There are places where choosing relatively heavy components makes sense. We equip most Bicycle Quarterly test bikes with leather saddles, because we ride them over long distances. It’s hard to feel positive about a bike when you’re uncomfortable… and we haven’t found a superlight saddle that’s as comfortable as a leather saddle that’s shaped to our very personal anatomy. However, we usually choose saddles with titanium rails, which save 80 grams and flex more to improve comfort further.

When taken to extremes, the search for light weight can compromise function and longevity, but that doesn’t need to be the case. Well-designed and well-made components are light, strong and durable. The bikes we ride – and the components we make – are designed for everyday use over a very long time. My first Rene Herse (above) is now 10 years old and has been ridden for more than 50,000 km (30,000 miles), including two Paris-Brest-Paris, a Cascade 1200, the Oregon Outback and many other challenging rides. It’s still equipped with its original parts, and it still performs as well as it did when it was built. And thanks to its lightweight feel, it’s still a joy to ride.

Further reading:

• The All-Road Bike Revolution: Make Your Bike Fast, Comfortable and Reliable