Introducing the World’s Lightest Front Derailleur

What is going on at Rene Herse Cycles? One day we talk about the latest Enve carbon wheels and why they have hooks again. And then, just a few days later, we introduce a direct-lever derailleur that is about as far from modern carbon bikes as you can get. Obviously, the Enve wheels and the Rene Herse derailleur won’t go onto the same bike—although in theory they could!

The reality is that we love and support many different ways of enjoying our bikes. Just like we make ultra-fast and grippy road tires and dual-purpose knobbies that have won the ultra-tough Silk Road Mountain Race more often than any other tire. We’ve never believed in the arbitrary divisions between cyclists, where road cyclists supposedly don’t like gravel bikes, mountain bikers disdain those who prefer smooth pavement, and ‘retro-grouches’ pooh-pooh modern carbon bikes. That’s not our experience. The reality is that most riders love—or at least respect—cycling in all its forms. Yesterday, I rode my OPEN MIN.D. carbon road bike with electronic Campy shifting, but my previous ride was on my analog Rene Herse with its Nivex rear and lever-operated front derailleurs. I love both bikes, and our goal at Rene Herse is to make tires and components that give you the best performance, reliability and fun on your bike—regardless of how you ride. And since nobody else is perfecting analog bikes these days, we’ve stepped up to the plate.

We are no strangers to superlight parts: At 75 grams, the Rene Herse cantilever brakes are the lightest brakes you can buy today. So it’s only natural that, when we build a front derailleur, it’s going to be light without compromising reliability.

Eighty-six grams. That makes the Rene Herse front derailleur by far the lightest of its kind today, especially since the weight includes the shift lever—and there is no shifter cable. It’s also one of the best-shifting: The direct lever allows you to push the chain with force, just like the motor does on an electronic front derailleur. For downshifts, you can feel when the chain comes off the big ring, so there’s little risk of dropping the chain beyond the small ring. Another plus: The derailleur cage floats freely, so there is no need to trim the front during rear shifts: The chain just pushes the shifter fork until it no longer rubs.

Is it difficult to operate? About as difficult as retrieving a bottle from the cage on the seat tube. If you can do that while turning the pedals, you can shift this derailleur. The photo at the top shows Natsuko and me on our tandem in full flight during a quick front shift. And I’m not particularly flexible… That derailleur is a mid-century original. We’ve added limit screws to make setup easier and refined a few other parts.

Despite all these strong points, we don’t expect many riders to use our new derailleur. Let’s be honest, reaching down means shifts are never going to be as fast as with the latest electronic derailleurs. A direct-lever front derailleur makes sense if you run a small ‘big’ chainring, which you use most of the time. Then you shift to the small ring only on steep hills. Think of it as a ‘One-By-plus-Granny.’ In that scenario, most shifts are on the rear, where our Nivex rivals the speed of modern electronic derailleurs.

I enjoy shifting the direct-lever derailleur even on hilly terrain—above I’m shifting during the 1,200-km Paris-Brest-Paris after more than 24 hours on the road.

The main reason to use this derailleur is because you enjoy analog bikes and want to feel the chain move when you shift. The light weight, simplicity and reliability are obvious benefits, too. That’s why I used my analogy bike for the FKT ride on the Oregon Cascades Volcanic Arc 400 earlier this summer (above). I also find that riding an analog bike makes the time and miles go by faster during ultra events.

Perhaps the biggest drawback: The derailleur needs dedicated attachments on your bike’s seat tube. You can’t just bolt it onto your bike. Basically it’s intended for custom bikes, even though it could easily be retrofit by a framebuilder. Originally it was intended for our limited edition run of 80th anniversary Rene Herse bikes. We got a lot of requests from riders and builders who wanted one for a project, so here they are.

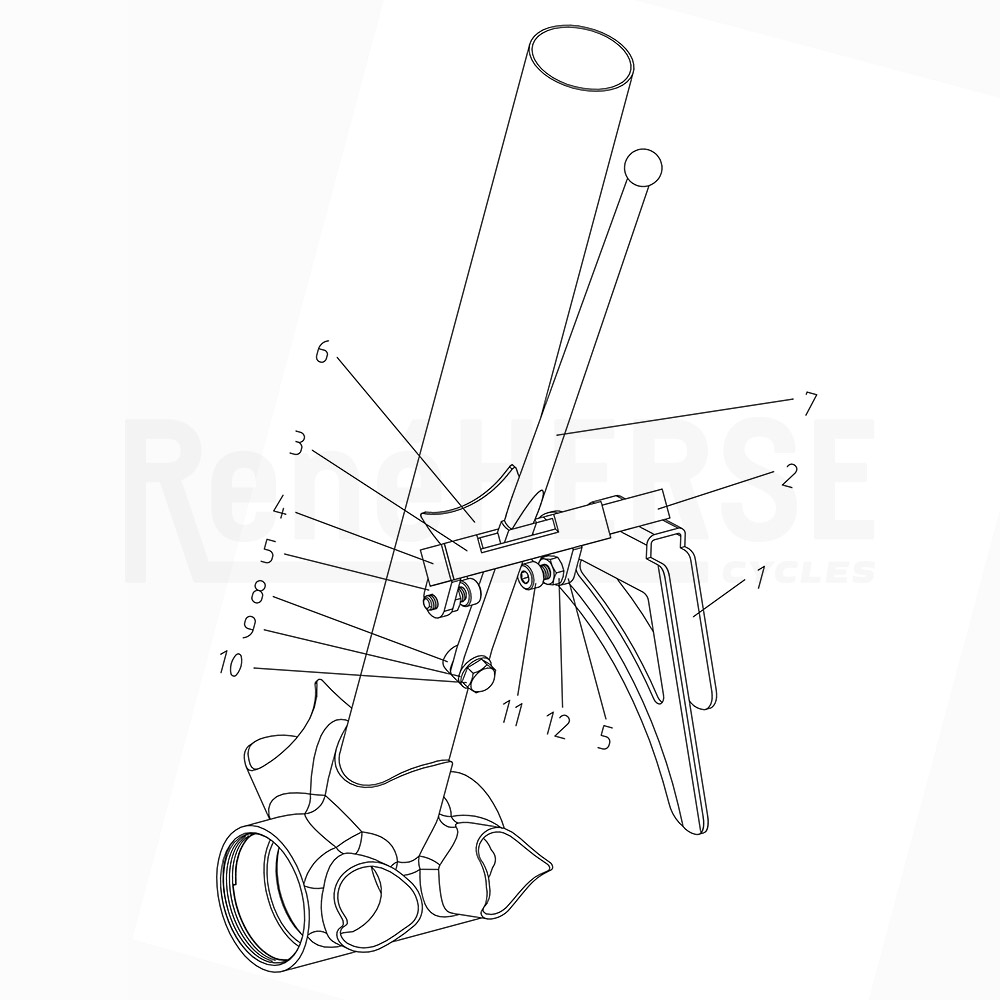

What you get is a kit with all the parts. It may just look like a few small pieces of metal, but they are pretty special. There’s the shift lever, machined from aluminum and tapered for extra stiffness, so you get forceful upshifts that rival those of modern electronic derailleurs. The shifter fork is formed by hand and includes a cutout on the inner plate to save weight. The square tube on the frame needs to be broached on the inside so it provides a perfect fit for the shaft of the shifter fork. And the bolt that holds the shift lever on its pivot is made from titanium. We could make it from aluminum, but we’ve got an aversion to aluminum bolts: They tend to strip or break once you’ve removed and installed them a few times.

Here is how it all fits together. For the square tube (3) that goes onto the seat tube and guides the derailleur, we provide two versions: One has the slot already machined, which requires ultra-careful brazing to prevent distortion. The other is uncut and more forgiving—you cut the slot after it’s on the frame. The end cap (4) that closes the left side of the square tube is supplied round rather than square: It tends to rotate when it’s brazed on. The builder files it square after it’s brazed-on, with a few file strokes.

Speaking of brazing, we’ve developed two jigs that align all the pieces during assembly. The Shifter Jig (above) is for brazing the shifter fork onto the square shaft that guides it in the frame.

The Frame Jig is for brazing the square tube and lever pivot onto the frame. It has holes to locate the derailleur for different chainring sizes. Smaller chainrings (up to 4 teeth) can be used, but not larger ones—the builder locates the derailleur for the largest chainring that may be used on the bike.

First you braze the lever pivot onto the seat tube…

…and then the square tube that guides the derailleur.

I’ve got to admit: When I made the first of these derailleurs, based on René Herse’s original mid-century design, I thought it was a novelty. I enjoyed shifting it so much that my next bike was going to have one, too. Analog shifting doesn’t make me faster, but it also doesn’t slow me down. And it puts a smile on my face, even during strenuous efforts like the Oregon Outback FKT ride (above) of Unbound XL.

We’re only making a very small number of the Rene Herse Direct Lever Front Derailleurs. If you want one, here’s your chance. And even if you don’t, we are sure you’ll agree that these derailleurs make the cycling world a (slightly) better place. They are in stock now.

More Information:

- Derailleurs in the Rene Herse program

- A steel bike lighter than carbon

- Supple Rene Herse tires for road, all-road, gravel and adventure bikes

Photos: Nicolas Joly (Photos 1 and 3); Rugile Kaladyte (Photo 9)