UAE Tour and Tubeless: What is Safe?

If you are following bike racing and/or tech, you will have heard of Thomas De Gendt’s mysterious crash during Stage 5 of the UAE Tour in Abu Dhabi. Video footage shows the front wheel of the Belgian breakaway specialist jerking to the right before he falls. After the crash, De Gendt’s bike is leaning against the guardrail, its front tire off the rim and a ripped green tubeless insert jammed between fork crown and tire. (The insert is supposed to keep the bike rideable even with a flat tire.) There is tubeless sealant all over the front wheel.

Fortunately De Gendt was not seriously hurt, but the incident has caused a lot of concern. Tires are not supposed to blow off the rim out of the blue. Imagine this happening when a peloton descends a mountain pass…

If even the ace mechanics of pro teams can’t keep high-end tires and rims stay together, what does this mean for average cyclists? What caused the crash? And more importantly, how can we as cyclists avoid risking similar accidents? What is safe and what isn’t?

Rene Herse Cycles has been involved with tubeless tires almost since the beginning. Some of us started riding tubeless more than 10 years ago, eager to try this promising new technology. Back then there were no tubeless tires and rims yet: You converted standard rims and tires to tubeless—with mixed results. We’ve been involved with setting the current tubeless tire standards via the ASTM (American Society of Testing and Materials), ISO (International Organization for Standardization) and ETRTO (European Tyre and Rim Technical Organization). In the end, the ISO adopted the ETRTO standards, which why the ETRTO now effectively sets all standards for car, bicycle and motorcycle tires world-wide.

That’s why the discussions and analyses since De Gendt’s accident have a familiar feel… We’ve been there and thought about these things for a long time.

What exactly happened? Here is what we know: Nobody saw the accident in enough detail to know with certainty. De Gendt’s tire came off on a straight, wide, smooth road. The manufacturers of tire and wheel issued statements suggesting that a big rock was to blame for the accident, not some technical issue with rim or tire. However, neither tire nor rim maker have yet been able to examine the parts involved in the incident, and no rock has been found, so nobody really knows anything specific yet. Once the tire and rim are examined, we may know more: In our experience, impacts from rocks will destroy the tire before it comes off the rim. If the rim itself is severely damaged, it’s conceivable that the tire would come off the rim. However, the insert is supposed to prevent rim and tire damage when hitting big rocks, in addition to providing run-flat capabilities.

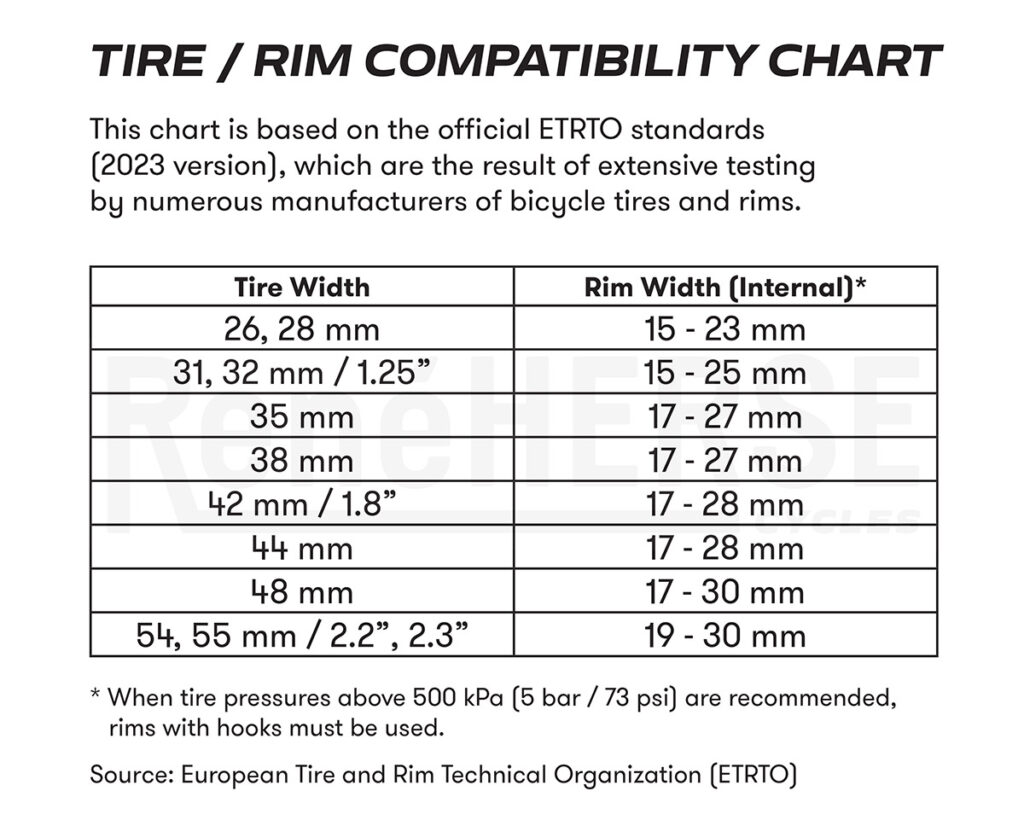

The UCI (Union Cycliste Internationale) and the professional rider’s union CPA (Cyclistes Professionnels Associés)—so many acronyms!—have not been satisfied with the suggestion that a big rock caused the accident. The UCI has started its own investigation, while the CPA has called for banning hookless rims. Some observers have pointed out that De Gendt was running a 28 mm tire on a 25 mm rim (internal width). This combination has been somewhat contentious: First it was allowed by the ETRTO in their updated 2022 tubeless tire standards. Last year, the ETRTO reversed course and changed their brand-new standards to require at least 29 mm-wide tires for 25 mm-wide rims. Did running too narrow a tire on too wide a rim cause De Gendt’s accident?

At this point, we don’t know anything for sure, but it’s possible that pushing the limits of rim width contributed to the accident. Here is what we know:

- Like most current carbon rims, De Gendt’s didn’t have hooks that serve as ‘insurance’ and help keep the tire on the rim.

- De Gendt’s tire/rim combination was recently removed from the permitted combinations by the ETRTO.

- De Gendt was running supple Vittoria Corsa Pro tires.

- Hot temperatures—as experienced in Abu Dhabi—make rubber softer and may have contributed to the accident.

What we’re seeing here is a confluence of factors that are all pushing the limits. A slightly-too-wide rim for the tire… No hooks for insurance… Hot weather that makes the rubber softer… Supple tires that don’t have a stiff sidewall pushing it down onto the rim…

The last point—supple tires requiring tighter tolerances—is actually why Rene Herse Cycles got involved in the process of developing tubeless standards. We were concerned that the standards might only factor in stiff tires, which are easier to keep on the rim simply because of their stiffness. A stiff sidewall helps push the tire down onto the rim, but a supple tire relies almost exclusively on the bead to keep it on the rim. That means supple tires, like most high-performance parts, need tighter tolerances.

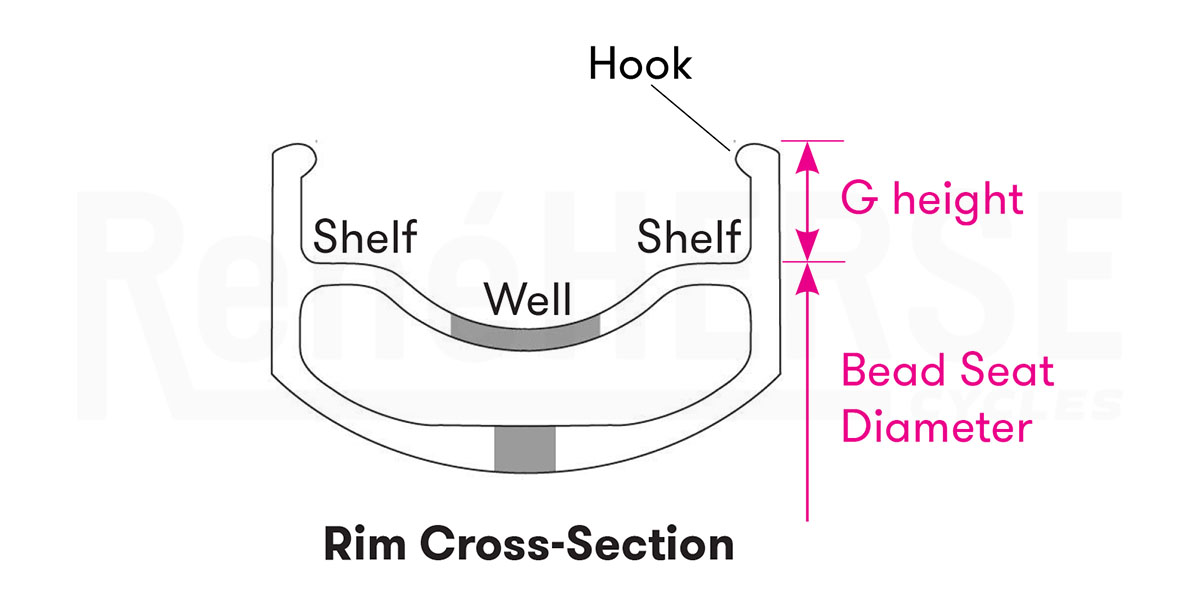

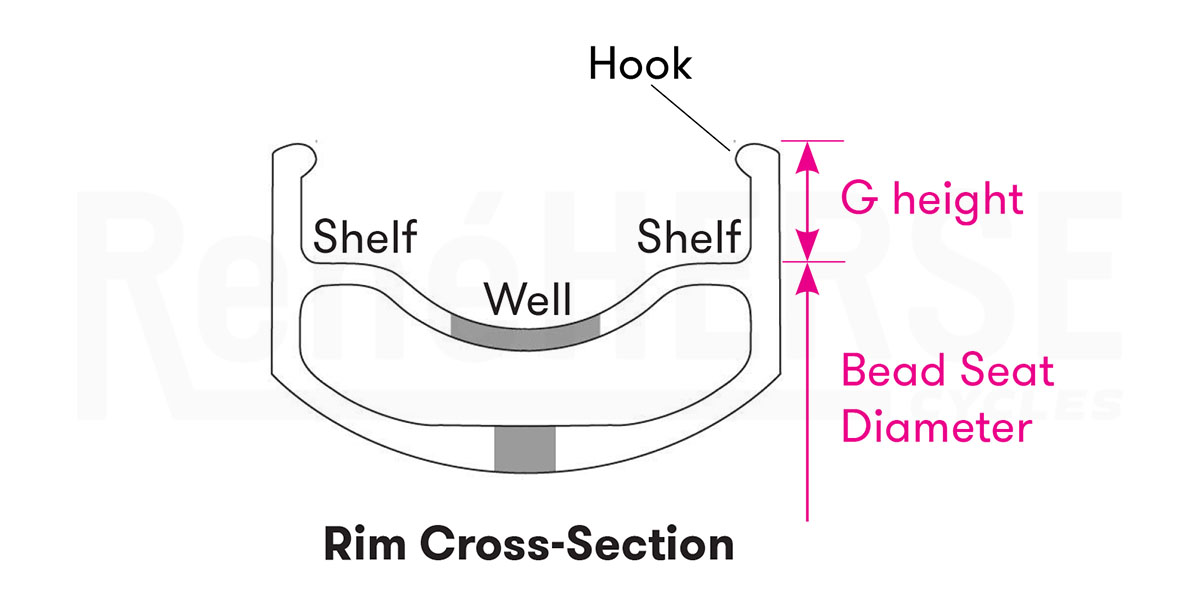

Our goal was to ensure that the new standards did not rely on the stiffness of the tire sidewall to keep the tire on the rim. In other words, we wanted to make sure that the new tubeless standards didn’t create rims that made it unsafe to run supple tires tubeless. Like the CPA (the racer’s union), we were initially concerned about hookless rims, and we tested the blow-off pressures of tires on a variety of rims. I presented our data at the 2019 ASTM meeting on tubeless standards. We found that hookless rims do have a lower blow-off pressure, but that other factors like correct G height and Bead-Seat Diameter (BSD) are more important. Basically, hookless rims are fine if their dimensions are correct.

In fact, with carbon rims, hookless can be better than rims with hooks. Here’s why: Carbon rims are made in molds, which makes it difficult to create a hook. You need a multi-part insert (or an inflatable bladder), so you can remove the mold from the finished rim. (The hooks lock against the part of the mold that creates the tire well.) Additional mold pieces or bladders add variability in the rim’s dimensions. Without the hook, you have a simpler mold and get more consistent rims. That means you have fewer rims that fall outside the acceptable tolerances for G Height and Bead-Seat Diameter.

The CPA’s suggestion to ban hookless rims, while making sense in theory, wouldn’t help make pro cycling safer in practice. Perfect hookless rims are safer than so-so rims with hooks. For added safety, ETRTO standards specify a 0.5 mm higher sidewall (G Height) for hookless rims.

It’s a different story with aluminum rims. They are made from extrusions, which are rolled (bent) into a circle and then welded or riveted together. With an extrusion, it’s easy to make a hook, and it’s important, because the Bead-Seat Diameter tends to be a bit more variable on rolled metal rims. With aluminum rims, the hook doesn’t affect how the rim is made, and it serves as important ‘insurance’ if the rim is a bit undersize due to manufacturing tolerances. That’s why almost all aluminum rims have hooks.

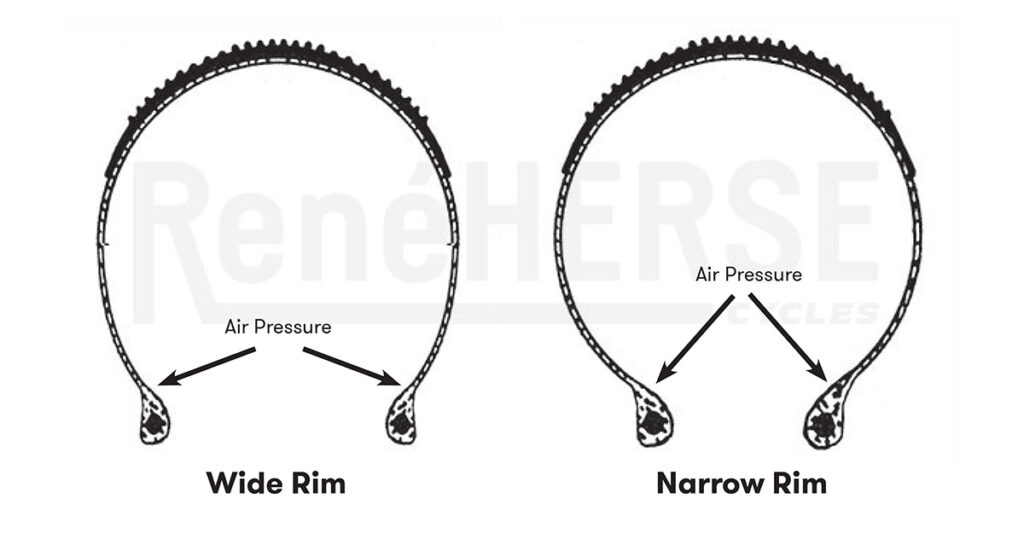

Back when we worked on establishing tubeless tire and rim standards, there was a big push from rim makers to allow 28 mm tires on 25 mm rims (internal) for aerodynamic reasons. Several tire makers, including Rene Herse, were against this. Why is a wide rim a problem? As the rim gets wider, air pressure no longer pushes the tire bead down onto the rim with the same force. That means it’s easier for the tire to blow off the rim.

I found out that the rim makers had done their testing with relatively stiff tires, where the sidewall stiffness helps keep the tire on the rim. In the image on the left, imagine the tire as a stiff pipe that doesn’t flex. It’ll be hard for the bead to move upward. If the tire sidewall is very supple and flexible, the bead can move upward with almost no resistance—the tire can blow off the rim.

Our concern was that with ultra-supple Rene Herse tires, the new standard was cutting it too close for safety. At first, our concerns were ignored, and the new ETRTO tubeless standards allowed 28 mm tires on 25 mm rims. Then something almost unheard of happened: Just a year later, the ETRTO revised their brand-new standards and disallowed the 28 mm tire/25 mm rim combination. The ETRTO now requires 29 mm tires as the minimum on 25 mm rims.

The new ETRTO standard is interesting, because almost nobody makes 29 mm tires. This gives tire makers the option to develop 29 mm tires, if they are comfortable getting close to the limit (and if their tires have stiff sidewalls). Or they can stick with 30 mm tires for an added factor of safety. (The ETRTO standard specifies a maximum rim width of 25 mm for this tire size, too.)

At Rene Herse Cycles, we tend to be conservative when it comes to rider safety. That’s one reason we made our new road tubeless Orondo Grade tires 31 mm wide. That way, there is a sufficient margin of safety on 25 mm rims (the widest ETRTO specs allow for tires up to 32 mm wide). For our Orondo Grade tires, we also use an extra-strong bead material—the strongest that’s available today. This material costs a lot more. It ensures that the tire stays on the rim even at relatively high pressures. Many other companies use a hybrid bead that consists mostly of less-strong Kevlar. This is significantly less expensive, but doesn’t offer the same margin of safety.

What is safe?

What matters for cyclists isn’t why De Gendt crashed, but what is safe to ride on their bikes. On twisty mountain descents, when we’re leaning our bikes deep into turns at high speeds—above Rene Herse co-owner Natsuko—we don’t want to worry whether our tires will come off their rims. Based on a decade of experience with tubeless tires, we can provide some guidelines:

Tubeless is safe

Tubeless tires are generally safe. Hundreds of thousands of tubeless tires are ridden every day with very few incidents. When accidents happen, they are almost always caused by incompatibilities between rim and tire (non-adherence to ETRTO standards) or some other technical issue, like a damaged tire, excess pressure, or lack of liquid sealant. In fact, there hasn’t been a single incident of a Rene Herse tire blowing off a rim that wasn’t traced to one of the above causes.

Hookless rims are safe

As explained above, hooks add insurance in theory, but in practice they also result in more variability in the rim dimensions (with carbon rims). Well-made hookless rims that meet the ETRTO standards are safe to use tubeless.

Make sure your tire is compatible with your rims

On the Rene Herse website, we publish the allowable rim widths in the specs for each tire. This information is based on the ETRTO compatibility chart shown above. You can see that it’s fine to run relatively narrow rims, but wide rims can cause problems. If your tire/rim combo is outside the ETRTO specs, it may work OK, but it’s not something that the tires and rims have been designed to do. Especially with supple tires, it’s important not to push the envelope too far. Stay within the tire/rim combinations allowed by the ETRTO, and you’ll be safe, at least with Rene Herse tires. (Probably with most other brands, too, but we can’t speak for them.)

Special tires for hookless rims?

We sometimes are asked whether there is a need for special tires when running hookless rims. The answer is no—at least for Rene Herse tires. The same tires work with hookless rims and those with hooks.

Rim dimensions must meet ETRTO standards

This is a very important point that wasn’t a factor in De Gendt’s accident. Most high-end rims from reputable makers meet the ETRTO standards for G height and Bead-Seat Diameter, but many other rims do not.

Here is how the ETRTO standards work: The dimensions of the rim are clearly defined, as well as the allowable tolerances. That’s the baseline for the system. Then it’s up to tire makers to make sure that their tires work on all rims that meet these standards.

Why are there no standards for tires? Because that would make the ETRTO responsible for designing tires—and if there was an accident with a tire and rim that met the standards, it would be the ETRTO’s fault. Tires are made from rubber, so their properties are much harder to define. That’s why the ETRTO defines the standards for rims, and leaves it up to tire makers to make sure their tires work on all rims that meet these standards.

Rim makers have the easy job: They just have to make sure that their rims meet the dimensions and tolerances specified by the ETRTO. Tire makers shoulder a bigger responsibility: They have to figure out how to make tires that work on every rim that meets these ETRTO standards. If something goes wrong, the rim maker can blame the tire—unless the dimensions of the rim fall outside the ETRTO standards.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of rims that do not meet ETRTO standards. We’ve measured a bunch of rims, and published the results in a post a few years back. Why don’t all rims meet ETRTO standards? I suspect there are a variety of reasons. The ETRTO is financed by membership dues from tire and rim manufacturers, and the standards are available only to members. It’s not cheap to join, and many small rim and tire makers apparently prefer to save the cost. Another reason is that a short G height makes the rim stronger and less likely to crack during an impact. That’s appealing to some rim makers, and it may work fine in testing with whatever stiff tires they have on hand. But what if riders want to run supple high-performance tires?

Some rim makers say they don’t agree with the ETRTO standards. That’s fine—but then they need to tell customers that their rims do not meet the standards. And they need to specify which tires they have tested on their rims—and assume full responsibility for those combinations being safe. Otherwise, tire makers would have to design tires for rims with unknown dimensions. That’s impossible. And that’s why there are standards in the first place.

Rims that don’t meet ETRTO standards can be frustrating for customers. Most of us would assume that any rim we buy should be compatible with any tire—as long as we don’t mis-match rim and tire widths. When a tire blows off—hopefully in the workshop and not on the road—and we find out that our rims aren’t safe to use with any high-performance tire, we are upset—and rightly so. If you have doubts about your rim, ask the maker if your rim meets current ETRTO standards. Ask them specifically to give you the specs and tolerances for bead seat diameter and G height. If the maker doesn’t know or won’t tell, that’s a bad sign…

Check your sealant regularly

With tubeless-compatible tires, the sealant not only serves to seal small punctures, but it also seals the tire/rim joint. If the sealant dries out, the tire can suddenly break loose from the rim and lose all air pressure. Then the tire can come off the rim. (The sealant that sprayed all over the front wheel shows that this wasn’t a factor in De Gendt’s crash.)

Watch your tire pressure

The higher the pressure, the greater the risk of a blow-off. That’s why there’s a max. pressure spec for tires—and for rims, too. Make sure you stay safely below the max for tire and rim, whichever is lower. Factor in that tire gauges can be up to 20% off. If your gauge shows 75 psi (5 bar)—roughly the max for hookless rims and tubeless tires—you may actually have inflated your tires to 90 psi (6 bar)!

For most riders, there is no need to max out the tire pressure. Our research has shown that high pressures provide no benefits. Most cyclists can ride much lower pressures than they are used to. Check the Rene Herse Tire Pressure Calculator for guidance on what pressure is recommended for you. And remember: Wider tires run at lower pressures. If you’re close to the limit, simply move up a tire size or two, and you’ll be back in the safe zone. (You’ll also be more comfortable and just as fast. The aero advantages of matching tire and rim widths are so small that you’re unlikely to notice them on the road.)

Inner tubes add a big margin of safety

Inner tubes reinforce the tire/rim joint. This greatly increases the blow-off pressure for a given rim/tire combination—by 30% or more with hookless rims. Anybody who has been riding for more than a decade remembers when road tires were inflated to 130 psi (9 bar) or more. That’s almost impossible with tubeless tires… which shows you how much a tube reinforces the system. If you have doubts about your rim/tire combination, you can install a tube and sleep well at night. Tubeless has many advantages, but they don’t outweigh the risk of a serious accident if your rims are not to ETRTO specs.

Interestingly, quite a few riders at last weekend’s Strade Bianche race over the gravel roads of Tuscany rode with inner tubes, including the women’s winner, Lotte Kopecky. However, the majority was on tubeless tires (and a few on tubulars). Clearly all three tire systems work for the pros, even on gravel.

You can run inner tubes in all tubeless Rene Herse tires. (Don’t run tires tubeless unless they are tubeless-compatible.)

Summary

Thomas De Gendt’s accident is a reminder that supple high-performance tires require closer adherence to the standards than stiffer tires. Here at Rene Herse Cycles, we’ve known that all along, and we’ve designed that into our tires. We are confident that all Rene Herse tires—tubeless or tubed—are safe to use on all rims that meet ETRTO standards, as long as you stay with the ETRTO-approved tire/rim width combinations. (We list the approved rim widths for each tire on our website’s product pages.)

I ride tubeless tires on many of my bikes, and I have no concerns descending at 50 mph (80 km/h) or more. Because when I’m riding my bike, the last thing I want to worry about is mechanical problems. And neither should you.

Further Reading: