What Would René Herse Build Today?

When Lyli Herse asked me, 15 years ago, to carry Rene Herse Cycles forward, I was very honored. I had long admired her father’s work (as well as hers and that of her husband Jean Desbois). Their bikes had inspired our research, and they formed the foundation for the all-road bikes that we were developing for our rides and adventures in the Cascade Mountains. The goal was always to take Rene Herse Cycles into the future, not to recreate the past—but it’s natural to wonder what René Herse would build today, if he was still running his shop in Levallois, on the outskirts of Paris.

To understand Rene Herse, it’s important to see his creations in their own time. His bikes may look like charming classics today, but they were the world’s most high-tech bikes in their day. In the photo above, Herse is watching his riders (in the Herse blue jerseys) as they compete in the 1955 Poly de Lyon hillclimb race. Among his customers were the fastest, strongest, most intrepid riders of the time—and many others who simply appreciated the joys of riding a superb bicycle.

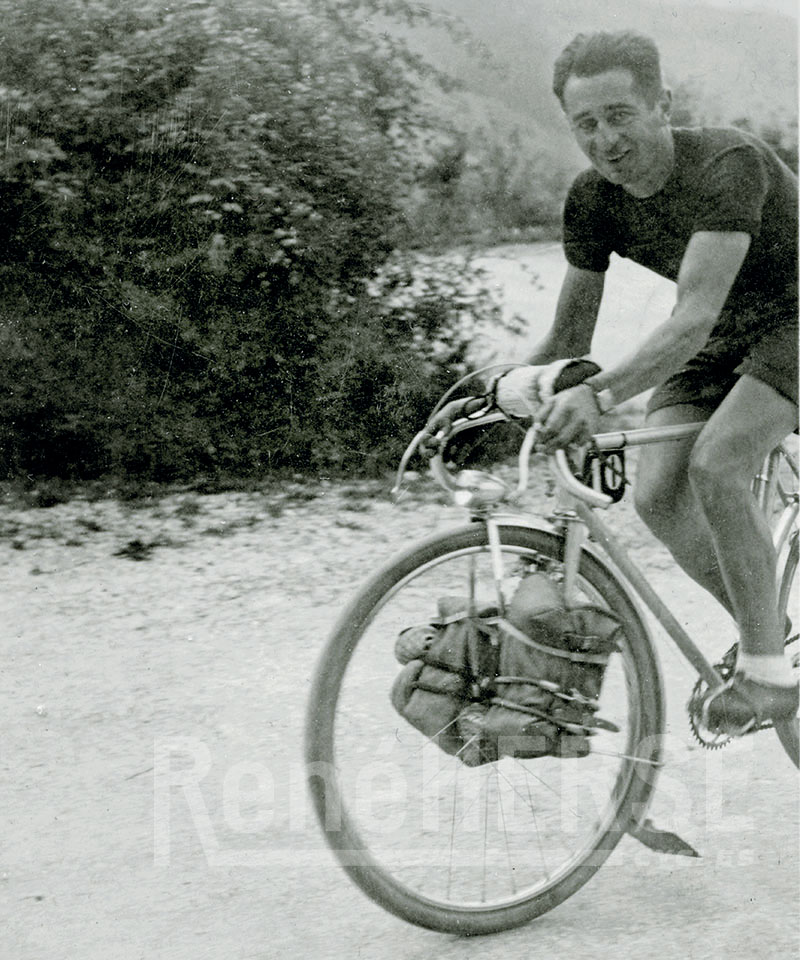

René Herse started his career making parts for prototype aircraft, including the first plane to fly from Paris to New York against the prevailing winds in a 37-hour non-stop flight—a milestone in aviation history. Herse was an avid cyclist, and it didn’t take long for him to realize that the then-current bikes could be improved. Herse quit his job at the Breguet aircraft factory and applied his know-how first to bike components and then complete bicycles, to make them lighter, faster and more reliable. He was called the ‘Magician of Levallois’ because his bikes were so incredible.

René Herse entered the cycling world at the 1938 Concours de Machines , with a bike that weighed just 7.94 kg (17.50 lb; above). It was by far the lightest bike at the Concours. That weight included racks, fenders, lights, and even the pump. The bike had to carry 3 kg (6.6 lb) of newspapers to prove its durability. The test course went over 700 km of rough gravel roads in the Alps, with 10,000 m of elevation gain. René Herse completed the stages not far behind the fastest amateurs of the time.

Fast forward a few decades, and René Herse presented a 6.8 kg (14.99 lb) racer at the 1973 Salon de Paris. It was the lightest bike at the show. In fact, that weight was exactly at today’s UCI minimum—27 years before the UCI established the limit. Clearly, Herse had lost none of his magic touch.

Those two bikes bookend his career. (He died in 1975 and passed the company on to his daughter Lyli.) In between, he made a little over 6,000 bikes that were ridden to many wins, including two world championships, but also on adventures and leisurely rides all over the world.

Does that focus on light weight mean René Herse would be making carbon fiber bikes today, like our OPEN x Rene Herse collab? I have no doubt that he’d be fascinated by the new materials. In the 1950s, he already experimented with stainless steel frames and other innovations. He would like the performance and feel of the best carbon bikes, which ride very similar to his own bikes. He’d probably acknowledge that for a typical ride, carbon bikes are hard to beat. It’s easy to see a bike like this in the Rene Herse program.

I also think Rene Herse would have continued to build his wonderful randonneur bikes. He loved long distance events. In the 1200 km Paris-Brest-Paris, his bikes won the ‘Challenge des Constructeurs’ —the prize for the builder with the highest-placed bikes—in every edition during his lifetime, except once (in 1971).

Would his randonneur bikes today be made from carbon? I don’t think so. A number of people have tried to make superlight rando bikes from carbon, but nobody has succeeded to make one that’s lighter than my PBP bike (above) or J. P. Weigle’s entry in the 2017 Concours de Machines that weighed just 20.0-pound (9.07 kg). Why aren’t carbon bikes lighter? The weight savings on a fully-equipped bike are in the attachments for the accessories. Bikes like the Herse and the Weigle are superlight because fenders, racks and lights are integrated into the design. There are no clamps and brackets—which weigh a lot once you add them all up. Steel is well-suited to all those attachments—there are more than 25 on the bike above—whereas carbon works best when it can flow uninterrupted.

Would René Herse have developed a desmodromic mechanical derailleur like the Nivex that equips my PBP bike? Maybe not—he’d probably run electronic shifting on his bikes. But I think he’d approve of the idea of pushing the ‘analog’ bike to ever-greater heights. For René Herse, the aesthetics and feel of his bikes were as important as the performance. One of the riders on his team remembered: “René Herse was happiest when he was at an event, surrounded by beautiful bikes.”

Many of René Herse’s bikes were designed to be ridden on gravel, because mountain roads weren’t paved yet. His riders didn’t seek out gravel for its own sake, but they didn’t avoid it, either. Cyclists who preferred pavement stayed in the lowlands around Paris. Many of René Herse’s customers headed to the Alps because they enjoyed challenge and adventure. They loved exploring. They loved quiet roads. They loved the sense of achievement of having climbed a big mountain pass (or several).

That’s similar to gravel riding today: Many of us ride on gravel not just because gravel is fun, but also because gravel roads tend to be quieter and more scenic than paved highways. I think it’s safe to say that Herse would have embraced today’s gravel scene. And he would have loved the challenge of making bikes that perform optimally on the Oregon Outback (above), at Unbound, and in the Arkansas High Country Race.

I can imagine that Herse would endorse carbon bikes for rides and races where luggage, lights and fenders aren’t needed. For longer adventures, his more specialized bikes wold probably still be made from steel. Carbon and steel may seem like polar opposites, but when you look at it from the perspective of ultimate performance for very different types of rides, it starts to make sense. Both materials have advantages, and Herse would optimize them to make bikes that offer the best performance and the most fun.

In the end, we’ll never know what Rene Herse would build today… All we can do is use him as our inspiration when we make components for no-nonsense bikes that match the performance, beauty and reliability of the machines made by the ‘Magician of Levallois.’ During my research into the René Herse story, I heard this time and again: “My Herse was the best bike I ever rode.” We hope that our customers feel the same.

More information:

- The OPEN × Rene Herse U.P.P.E.R. carbon frames are available for pre-order until November 14, 2022. More information is here.

- The Limited Edition 80th Anniversary Rene Herse Randonneur bikes are sold out. They are in production now.

- The record flight from Paris to New York with the plane that René Herse helped build.

- The complete René Herse story is told in René Herse: The Bikes • The Builder • The Riders